3 Chapter 2: Understanding Risk and Awareness

Introduction

In self-defense training, situational awareness is more than just observing your surroundings—it’s the ability to consciously perceive, understand, and interpret what’s happening around you. This chapter will guide you in developing self-awareness by recognizing how your own biases and past experiences shape your perception of potential threats, influencing the decisions you make about personal safety. We’ll also examine environmental awareness, focusing on practical strategies like knowing your exits and using peripheral vision to broaden your scope of observation. You’ll be introduced to the importance of mindset in understanding risk and awareness and study the color codes of alertness, an evidence-based method for connecting your mental state to your level of threat preparedness. Through a series of activities, you’ll practice scanning environments, identifying risks, and creating proactive safety strategies. By engaging in self-reflection exercises, you’ll bridge theory with real-world application, equipping yourself with the tools and mindset needed to navigate hazardous situations with confidence and vigilance.

Chapter Goals

After reading this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Define situational awareness and risk management in the context of ESD.

- Analyze factors influencing personal perception and their impact on risk assessment.

- Develop strategies for assessing and prioritizing risks in personal safety scenarios.

- Enhance observational skills to recognize pre-incident indicators and potential danger cues.

- Implement proactive measures for reducing vulnerability and increasing personal safety.

- Set practical personal safety goals to be incorporated into your daily activities.

What Is Situational Awareness?

Situational awareness is the ability to consciously perceive, interpret, and anticipate what is happening in your surroundings. It goes beyond simply noticing things—it’s about recognizing meaningful details, understanding how they relate to your safety, and projecting how situations might evolve. This active awareness allows you to identify potential risks early and make informed decisions to avoid harm or de-escalate danger.

At its core, situational awareness involves three interrelated processes:

- Perception – noticing relevant details in your environment, such as changes in people’s behavior or shifts in physical space.

- Comprehension – making sense of what those details mean in context.

- Projection – anticipating how a situation may unfold based on what you’ve observed.

This skill is critical not only in moments of physical threat but also in daily life—from navigating crowded spaces and avoiding conflict to staying alert while driving or engaging safely online. Cultivating situational awareness equips you to respond to your surroundings with clarity, confidence, and control.

How to Cultivate Situational Awareness

Situational awareness is not just a trait you either have or don’t—it’s a skill that can be developed with practice. Cultivating situational awareness means strengthening your ability to stay present, notice changes, and respond with intention. It empowers you to assess risks and make proactive choices that prioritize your safety and the safety of those around you.

This process begins by focusing on three key areas:

- Self-awareness – understanding how your own thoughts, emotions, and past experiences influence what you notice and how you react.

- Environmental awareness – scanning your physical surroundings for exits, obstacles, changes, or cues that something may be off.

- Observation of others – tuning into people’s behavior, body language, and tone to detect signs of discomfort, deception, or aggression.

By intentionally developing awareness in each of these areas, you become better equipped to recognize danger early, remain calm under pressure, and take effective action when needed. Situational awareness isn’t about being fearful—it’s about being prepared, present, and empowered.

Self-Awareness

Before you can clearly assess what’s happening around you, it’s important to understand what’s happening within you. Self-awareness allows you to recognize how your own experiences, emotions, and biases influence your perception of risk.

Subjectivity of Perception. Everyone sees the world through a personal lens shaped by past experiences, beliefs, and emotions. For example, someone who has experienced trauma may detect threats more readily, while someone without that context might miss the same cues. Recognizing this subjectivity helps you question your own assumptions and strive for a more objective view of your surroundings.

Varying Risk Thresholds. People have different comfort levels with risk. Some may act with extra caution due to past experiences or personality traits, while others may underestimate danger due to overconfidence. Knowing where you fall on this spectrum helps you recognize when your instincts may be skewed—either toward hypervigilance or dismissiveness.

Cognitive Biases. Mental shortcuts like confirmation bias (seeking evidence that confirms what we already believe) and anchoring bias (relying too heavily on first impressions) can cloud your judgment. Implicit bias—the attitudes and stereotypes we unconsciously hold—can lead to distorted evaluations of people or situations based on preconceived notions rather than objective reality. Becoming aware of these mental habits allows you to make more balanced, informed decisions.

Cultural Norms and Expectations. Cultural background plays a major role in shaping how we perceive safety and danger. What might be considered normal or harmless behavior in one culture could be seen as risky or suspicious in another. This cultural lens influences how we assess threats, respond to them, and even how we interpret the behaviors of others. For example, physical proximity that is considered acceptable in one culture might be perceived as invasive or threatening in another. Understanding these differences is essential in evaluating risks more objectively, especially in diverse or unfamiliar environments.

Peer Influence and Social Context. Peer pressure, group dynamics, or the behavior of those around us can shape how we evaluate potential dangers. For instance, in a group setting, an individual might feel compelled to downplay risks to align with the group’s norms or actions, even if their intuition signals otherwise. Conversely, in situations when peers express concern or fear, an individual may become more risk-averse than they would be on their own. Social dynamics can distort individual judgment, making it important to remain aware of how these influences affect our personal risk assessments.

Emotional Responses. Emotions like fear, anger, and stress can warp your perception. Fear might cause us to overestimate threats, leading to excessive caution or avoidance, while anger or stress may cause us to underestimate risks by pushing us to react impulsively or dismiss caution altogether. It’s crucial to recognize how emotions affect our judgment and take steps to regulate them to make more accurate and thoughtful risk assessments.

Intuitive Signals. Intuition plays a powerful role in assessing risks. Often, our subconscious mind picks up on subtle environmental cues—such as changes in body language, tone of voice, or behavior patterns—that our conscious mind might overlook. These gut feelings or intuitive reactions can serve as an early warning system, alerting us to potential danger before we can rationally process it. However, intuition is also influenced by our past experiences and biases, so it’s essential to develop a balance between trusting these instincts and verifying them with logical analysis.

Environmental Awareness

Knowing how to read your physical environment is a core part of situational awareness. This means actively scanning your surroundings for exits, barriers, potential hazards, and unusual activity.

Scan Your Environment. Whether you’re in a classroom, on public transit, or walking through a park, make a habit of visually scanning the space. Ask yourself: Where are the exits? Are there barriers or hiding spots? Where could I go for help if something went wrong? Become familiar with what is normal to see in the locations you frequent, and you will become more sensitive to when something or someone appears “off” or out of place. By developing the habit of assessing your surroundings, you equip yourself with the ability to recognize potential threats, plan escape routes and prepare for unexpected situations.

Know Your Exits. Become familiar with how you would leave a situation whether in a building, on public transportation, at an outdoor event, or on your walk to work. How would you escape the threat, and which direction would you run in if there was more than one option? Look for the location where the attacker can no longer harm you and you can get help. If it is an indoor enclosure, think doors, windows, and exits in unexpected places like the floor or ceiling. If it is a public space, scan your surroundings and look for the direction that provides the quickest exit to a safe area. Think of a direct path with no obstructions or barriers to an area that is well lit and contains people. Alternatively, if leaving the area is not immediately available, look for a barrier to put between you and the threat. This could be a bicycle on public transportation or a locked door in a building. Think about these things now and have a plan.

Peripheral Vision. Expand your awareness beyond what’s right in front of you. Practice noticing what’s happening to your sides and behind you. Improving your peripheral vision not only widens your field of observation but also reduces your reaction time. Studies show that the brain can process information in your peripheral vision up to 25% faster than what’s directly in front of you—an edge that can make a real difference in high-stakes moments.

Observe Other People’s Behavior

People’s behavior can offer critical insight into whether a situation is safe or shifting in an uncomfortable direction. People’s actions, expressions, and body language can provide valuable clues about their intentions and emotional states, helping you assess potential risks. Whether it’s a stranger, an acquaintance, or someone you know well, paying close attention to how they are behaving can give you insights into whether a situation is unfolding as expected or if something feels off. For instance, noting where their focus is—such as their gaze, tone of voice, and body language—can indicate whether they are relaxed, anxious, or potentially acting suspiciously. These subtle cues are essential in helping you identify risks early, giving you time to respond proactively.

Monitor Body Language. A person’s posture, movements, and facial expressions can give you clues about their emotional state or intent. Are they agitated? Fidgeting? Avoiding eye contact? Scanning the room nervously? These may be signs of discomfort or preparation for an action. Compare what you’re seeing with what would be “normal” for the setting—this contrast helps you identify what feels off.

Tune Into Tone and Language. People don’t always say what they mean—but their tone and word choice often reveal more than the content of their speech. Listen for abrupt changes in voice, nervous laughter, vague or evasive answers, or overly formal or rehearsed speech. These can all be signs of underlying tension or deception.

Compare to Context. Context is key. A behavior that seems odd in one situation may be completely normal in another. The goal isn’t to assume the worst—it’s to notice when something doesn’t fit the pattern. When combined with your environmental and self-awareness, this third layer of observation can help you stay grounded, alert, and prepared to act wisely.

By sharpening your awareness in these three areas—yourself, your environment, and others—you can cultivate a fuller, more accurate picture of what’s happening around you. Situational awareness is not about paranoia; it’s about presence. With regular practice, it becomes a natural part of how you move through the world—confident, informed, and in control.

Mindset and Alertness Levels: What Frame of Mind Are You In?

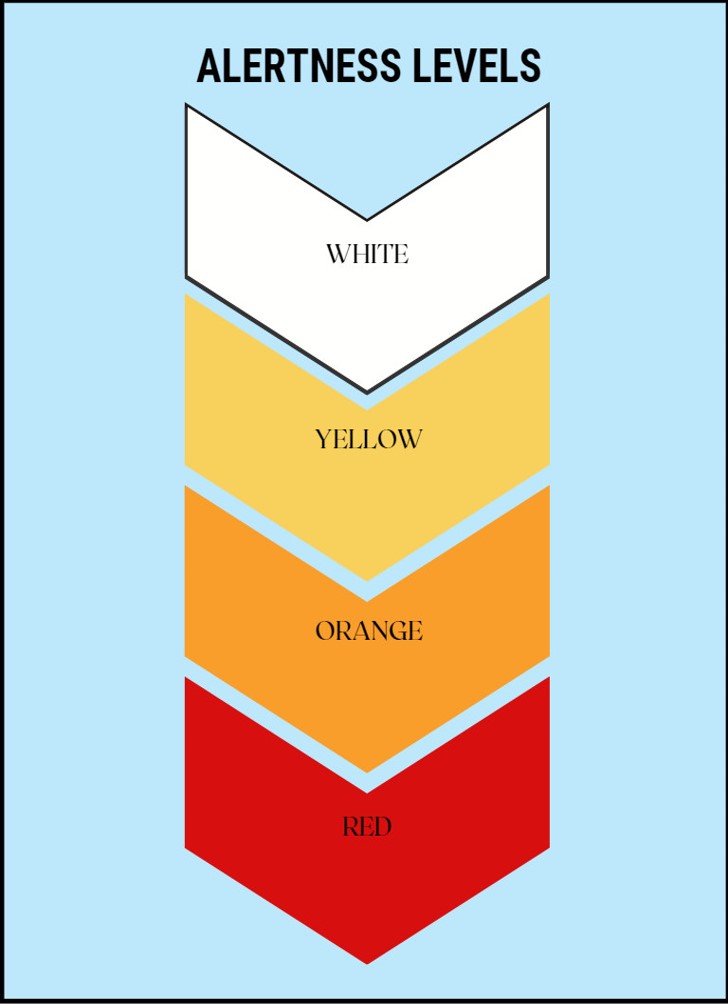

When it comes to personal safety and threat response, your mindset is just as important as your physical abilities. Before you can act, you must first perceive—and perception depends heavily on your mental state. A good place to begin developing situational awareness is by understanding your own mindset in relation to your environment. One widely used method for doing this comes from the color-coded system of alertness originally developed by U.S. Marine Colonel Jeff Cooper.

Though designed to help soldiers assess battlefield threats, Cooper’s color codes have since been adapted by law enforcement, self-defense instructors, and personal safety advocates to help people navigate everyday situations with greater awareness and confidence. This system works because it’s both simple and adaptable: by linking a color to your level of alertness, you create a visual and mental shorthand that helps you recognize your current state and shift it as needed—without panic or paranoia.

Understanding and applying these levels allows you to move through the world with a greater sense of control. Instead of reacting impulsively or freezing under stress, you have a built-in framework to assess risk and take appropriate action. In the following section, we’ll explore each color-coded mindset, how it connects to your awareness of your surroundings, and how this tool can empower you to respond more effectively when your safety might be at stake.

- White. You believe an attack will never happen to you. You may feel this way all the time or in certain situations. For instance, when you walk into your home or when you walk through your day-to-day life with a person next to you who you believe will keep you safe. In either case, this is unrealistic, and you are unprepared to deal with a threat. If one arises, you will have a delayed reaction or freeze and your mind will go blank, as you have the least amount of mental preparedness for a stressful situation.

- Yellow. You are relaxed but alert. You are aware of your surroundings, but no one and nothing seems out of place. You are not troubled. You know threats can come from unexpected places, but you have thought about this and have strategies to use if something troubles you. You know you can rely on yourself, and you are mentally prepared to deal with a stressful situation.

- Orange. You are relaxed but alerted to something out of place. You listen to your intuition and scan your environment for what seems wrong and then focus on it. You think about next steps and strategies to be safe. Nothing has happened, but you plan in case it does. You know where your exits are and what objects you can use to keep yourself from harm. You are aware of your body’s reaction to the potential threat, and you can remain calm and ready to respond.

- Red. An attack or confrontation is about to occur. You have already thought of a strategy, and now you are prepared to execute it. You have control over your emotions and physiological reaction to the threat. You use your verbal and physical tools to get safe as fast as possible.

In class, you may play games categorizing behavior according to the different color codes of awareness. What about in the real world though? My student Lucy found out when she was out shopping with a group of friends and felt something was wrong. She realized that as she moved around a large department store, she kept seeing the same person just outside her central vision. She listened to her intuition and immediately began to assess her safety options. By the time she drove away from the store, and he was following her, Lucy was ready to respond. She told one friend to take a picture of his license plate and the other friend to call 911 while she drove to the nearest police station. By having a readiness mindset, Lucy averted a threat and provided valuable information to the police by remaining calm and having a plan. And, yes, she did say the colors yellow, and orange flashed through her mind!

Movement Activities

Twenty-Minute Warmup

The warm-up (see Chapter 1) is to be done each week before learning or practicing physical techniques. This efficient warmup routine targets the entire body by beginning with alternating cardio movement and body weight strengthening exercises followed by a series of joint mobility techniques. Always take note of how your body is feeling before you start any form of exercise by quickly scanning your body for areas of stiffness, soreness, or pain. Modify the warmup as needed and know that simply moving your body for 20 minutes, no matter how big or small, is good for your health!

Where Are the Exits?

Explore, as a group or individually, the different ways you could exit the space you are in. Evaluate where each exit leads in terms of providing safety from a threat. Think about how you could help one another exit or use objects in the space to help remove you from a threat.

Then it is time to play tag! One person leaves the space and reenters as a threat, trying to tag the other students before they can exit. Have the group help set the parameters for the game.

Play this game with yourself when you enter a new space. Take a moment to develop an exit plan.

Having an exit plan has been shown to improve reaction time to a threat and the ability to avoid one altogether.

What Objects Are in Your Space?

What objects are nearby or available to use for protection? Turn and face a wall. Then, without looking, recall an object in the space and explain how it could be used for protection. This game can also be played alone or with a friend. Be creative and provide as many details as possible. Not only does it improve your situational awareness skills, it gets you in the habit of evaluating objects for safety purposes.

These awareness games are very popular with my students. They report playing them with friends and colleagues.

Peripheral Vision Game

Start with students in groups of three. One student starts to walk away from the others, keeping their gaze forward. One of the other students comes up on either side of the first student; they can choose how fast and how close they get to the walking student. As soon as the walking student sees movement out of the corner of their eye, they must turn toward it in a ready stance and shout “stop” or “back off.”

Stomp Strikes

The stomp strike is a powerful self-defense move designed to neutralize an aggressor using simple, gross motor movements. To execute the stomp strike, start in a ready or neutral stance with your hands up for protection and your gaze locked on the person in front of you. Lift your dominant leg with your knee bent close to your torso, ready to strike. For additional force, pivot on your standing leg as you bring your knee up, chambering it to the side of your target. Then, bring your heel or the blade of your foot down with as much force as possible onto the shin or top of your attacker’s foot. To increase the impact, shout commands like “back off” or “no” as your foot makes contact. This strike should only be used when you are close enough to physically reach the attacker—distancing is key to both the effectiveness of the move and your safety.

The importance of gross motor movements, such as the stomp strike, in self-defense cannot be overstated. When faced with a threatening situation, fine motor skills can quickly deteriorate due to adrenaline and stress. Techniques that require intricate finger dexterity, such as using your phone or a protective device, become more difficult, and precise targeting is less likely. Gross motor movements, however, are simpler and easier for your body to perform under pressure, making them more reliable when responding to an attack. A stomp strike is a direct and forceful movement that doesn’t require precision to be effective—it leverages your body’s natural strength and ability to deliver a powerful, damaging blow to sensitive areas of the attacker.

In self-defense, gross motor movements like the stomp strike give you the advantage of being quick, decisive, and impactful without needing to overthink the mechanics of the action. By focusing on strong, basic moves, you can effectively protect yourself, even in high-stress situations, while maintaining control over your body and the distance between you and the aggressor. Gross motor movements will be introduced throughout the course.

Actionable Strategies

After learning about risk management and situational awareness and practicing basic exercises like locating exits, recognizing defensive uses of objects in your space, strengthening your peripheral vision, and executing a stomp strike, there are actionable strategies to integrate these skills into your daily routine. Each strategy includes a breakdown of how it will be specific and measurable, provide accountability, and be time-bound. Try them on for size, adjust as needed, or come up with your own.

- Locate exits in any new environment.

- Goal: Build the habit of identifying multiple exit points for increased situational awareness and readiness.

- Specific: Make it a habit to identify at least two exits whenever you enter a new space, such as a classroom, café, or public event.

- Measurable: Track your consistency by writing down the locations of exits in a small notebook or digital notes app for 7 consecutive days.

- Accountability: Share this practice with a friend and compare notes or observations during your daily check-ins.

- Time-bound: Commit to this exercise daily for 1 week; then assess how natural it feels to locate exits without conscious effort.

- Practice recognizing defensive uses of everyday objects.

- Goal: Enhance creativity and quick thinking in identifying potential defensive tools in your surroundings.

- Specific: Choose one object in your immediate environment each day, such as a water bottle, book, or parked car, and identify how it could be used defensively.

- Measurable: Record your observations in a journal or app, listing the object, its defensive use, and the scenario for which it might be helpful.

- Accountability: Discuss your findings with a peer or ESD mentor, sharing ideas and gaining feedback.

- Time-bound: Dedicate 5 minutes a day to this exercise for 2 weeks; then evaluate how your situational awareness has expanded.

- Strengthen peripheral vision during daily activities.

- Goal: Improve your ability to notice subtle movements or objects in your peripheral vision to enhance overall alertness.

- Specific: Enhance your peripheral vision by practicing awareness exercises, such as noting the colors, movements, or shapes on the edges of your visual field while walking or sitting.

- Measurable: Perform this exercise for 2 minutes during two different activities each day, such as commuting or working at your desk.

- Accountability: Keep a brief log of your observations or use a visual-tracking app to assess improvement over time.

- Time-bound: Commit to this practice for 10 days and review any changes in your ability to notice details in your environment.

- Execute a stomp strike as part of your morning routine.

- Goal: Develop confidence, strength, and accuracy in using a stomp strike as a self-defense technique.

- Specific: Incorporate five repetitions of a stomp strike into your morning routine, focusing on form, power, and visualization of breaking through an obstacle.

- Measurable: Count your repetitions and gradually increase the number as your confidence and strength improve (e.g., starting with five and addingtwo2 per week).

- Accountability: Record a short video of your practice weekly to assess technique or share with an ESD instructor for feedback.

- Time-bound: Perform this exercise daily for 3 weeks; then assess your comfort and precision with the movement.

- Conduct situational scans while walking.

- Goal: Cultivate the ability to remain alert and aware of your surroundings during movement or transit.

- Specific: While walking, scan your environment for potential threats, safe zones, and items that could be used defensively. Focus on being alert rather than distracted by devices.

- Measurable: Set a goal to perform a situational scan for 5 minutes during each walk or outing. Use a checklist to note key observations, such as exits, lighting, or unusual behavior.

- Accountability: Pair with a friend or family member who can practice situational scans with you, sharing insights after each outing.

- Time-bound: Practice this daily for 2 weeks; then evaluate your increased confidence and awareness.

- Pair awareness exercises with daily tasks.

- Goal: Make situational awareness a natural and integrated part of your daily life.

- Specific: Choose a routine activity, such as grocery shopping or waiting for public transportation, to practice combining situational awareness and defensive readiness (e.g., noting exits, observing objects, and scanning for potential threats).

- Measurable: Document one key observation from each session, such as a useful object, a safe zone, or an area to avoid.

- Accountability: Share your reflections weekly with a group or accountability partner who is also practicing these skills.

- Time-bound: Commit to pairing these exercises with daily tasks for 3 weeks; then reflect on how naturally the practice has become part of your routine.

By integrating these strategies into daily life, you can develop stronger situational awareness, confidence, and the ability to respond effectively in challenging situations, making empowerment self-defense an active and empowering part of your day.

Key Takeaways

After engaging with this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Possess a comprehensive understanding of ESD, fortified by the ability to articulate situational awareness and risk management within its context.

- Understand the intricacies of personal perception, recognizing its intersection with risk assessment.

- Recognize potential risks across diverse environments and situations and be able to develop strategies to assess and prioritize them effectively.

- Sharpen your observational skills to recognize pre-incident indicators and danger cues involving people and the surrounding environment.

- Reflect on the role intuition plays in decision-making while discerning and mitigating personal biases, stereotypes, and cultural influences on risk assessment.

- Enhance your personal safety with proactive measures, including mindfulness techniques to bolster present-moment awareness amid hazardous circumstances. This holistic skill set equips students with the tools necessary for proactive risk mitigation and personal empowerment in navigating various scenarios with confidence and efficacy.

- Incorporate ESD strategies into your daily routine.

Resources

Christensen, L. W., & Christensen, L. (2016). Self-defense for women: Fight back. YMAA Publication Center, Inc.

Cooper, J. (1972). Principles of personal defense. Paladin Press.

Cooper, J. (2006). Principles of personal defense (Rev. ed.). Paladin Press.

Durso, F., Rawson, K., & Girotto, S. (2018). Comprehension and situation awareness. In F. Durso & K. Rawson (Eds.), The handbook of learning and cognitive processes (pp. 1–20). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315087924-6

Gallwey, W. T. (2008). The inner game of tennis. Random House.

Global Guardian. (n.d.). Situational awareness. https://www.globalguardian.com/global-digest/situational-awareness

Leggatt, A., & Henwood, K. (2015). Situational awareness in protective services. Journal of Safety Research, 54, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2015.03.003

Moxley, B., Jacobs, R., & Neuman, M. (2021). Be aware: Strategies for keeping you and your loved ones safe.

Ross, E. N. (2000). Being safe: Using psychological and emotional readiness to avoid being a victim of violence and crime. Hartley & Marks.

Resources

Fig. 2.1: Copyright © 2020 Depositphotos/ajphotos.

Fig. 2.2: Created with Canva Pro.

Fig. 2.3: Copyright © 2018 Depositphotos/Nomadsoul1.

Fig. 2.4: Copyright © 2014 Depositphotos/missisya.