2 Reading 1.1: Undercovering Assumptions We Hold About Human Development

Ellen Skiller, Thomas Kindermann, and Andrew Mashburn, “Undercovering Assumptions We Hold About Human Development,” Lifespan Developmental Systems: Meta-Theory, Methodology and the Study of Applied Problems, pp. 36-42. Copyright © 2019 by Taylor & Francis Group. Reprinted with permission.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a paradigm shift was taking place in developmental psychology in the United States, although most researchers were not aware of it at the time. As was true for the rest of psychology, behaviorism and experimental child psychology continued to dominate developmental psychology during this decade (Cairns & Cairns, 2006). However, newer perspectives were knocking on the doors of behaviorism. For example, as discussed in the last chapters, ethological evolutionary perspectives were replacing social learning accounts of attachment. And, in 1959, Robert White published a seminal article questioning the supremacy of acquired motivation and presenting a case for intrinsic motivation, which would usher in a motivational revolution (Deci, 1975).

Nowhere was this sea change felt more keenly than in the area of learning, which was at the core of the behaviorist agenda (Bijou & Baer, 1961). With the publication of The Developmental Psychology of Jean Piaget in 1963, John Flavell introduced American developmentalists to a grand European theory of cognitive development, and it was proving to be a contender to theories of learning. In fact, the late 1960s were awash in dueling studies attempting to empirically adjudicate this clash (for reviews, see Brainerd, 1972; Strauss, 1972). One set of replies and rejoinders focused on whether preoperational children’s reasoning is limited by structural constraints on their cognitive processes. To examine this question, Piaget and his followers had carried out so-called conservation experiments to see whether children could mentally conserve the properties of objects despite transformations in their appearance. First, they showed young children two objects (e.g., two short wide glasses filled with juice) and ascertained that children viewed them as identical (i.e., they contained identical amounts of juice). Then researchers transformed the appearance of one of the objects (e.g., poured the liquid into a tall thin beaker), and asked children if the properties of the transformed object had also changed (e.g., “Is there more juice, less juice, or the same amount of juice in these two glasses now?”). Preschool children seemed to be fooled by the transformation. For example, they would assert that the amount of a liquid increased when it was poured into a taller thinner glass, or that the number of candies increased when the candies were spread farther apart. As evidence of structural limitations, Piagetians focused on children’s reasoning and rationales for their assertions (e.g., “There is more juice because it’s taller in the glass now” or “There are more candies because now they go from here to here”). In response, learning theorists conducted studies showing that, with sufficient practice, coaching, and reinforcement, young children could be trained not only to give the reply indicating that there had been no transformation in properties (namely, “They are the same”) but also to provide the correct rationale (namely, “You didn’t add any or take any away, so they are still the same”).

Although couched in more scientific terms, it is possible to see in these exchanges behaviorists’ satisfaction in disproving Piaget’s theory, an implied, “So there! Now we have demonstrated that there are no structural limitations operating on children’s performance.” And the replies from Piagetians are equally instructive, basically, “Pah! You have trained these children to say some words—but because you taught children to say them, they are meaningless as indictors of children’s underlying reasoning, and so prove nothing.” And so on, back and forth. It was in this atmosphere of acrimonious and baffled exchanges that two well-respected researchers, one learning theorist, Hayne Reese, and one Piagetian, Willis Overton, joined forces to examine the basis of these claims and counter-claims, and especially to try to understand why researchers from these two camps seemed to be so successfully talking right past each other.

What did Reese and Overton think was going on?

The resulting chapter, entitled “Models of Development and Theories of Development” (Reese & Overton, 1970), and its accompanying methodological chapter (Overton & Reese, 1973) were not the first discussions of paradigms and paradigm shifts in psychology and science (e.g., Kuhn, 1962; Pepper, 1942), but they were the first to lay out the issues for developmental psychologists. Reese and Overton argued that the state of mutual incomprehension apparent in these empirical exchanges was based on the fundamental incompatibility of the underlying assumptions about human nature and human development that each side brought to the table unawares. Each camp had its own “model” of humans and of reality. As explained by Reese and Overton,

the most general models, variously designated as “paradigms” (Kuhn, 1962), “presuppositions” (Pap, 1949), “world views” (Kuhn, 1962, Seeger, 1954), and “world hypotheses” (Pepper, 1942), have a pervasive influence throughout the more specific levels, as noted by Kessen (1966) and others before him (Black, 1962; Peppper, 1942; Toulmin, 1962). the different levels of models are characterized by different levels of generality, openness, and vagueness. At one extreme are implicit and psychologically submerged models of such generality as to be capable of incorporating every phenomenon. these metaphysical systems are … basic models of the essential characteristics of [humans] and indeed of the nature of reality.

(1970, p. 117)

Such models, which we refer to as “meta-theories,” have advantages and disadvantages. As Reese and Overton go on to explain,

any model limits the world of experience and presents the person with a tunnel vision. Being committed to a particular model may make a person blind to its faults…. however, a good model increases the horizon, since one of its functions is to aid in the deployment or extension of a theory…. A good model acts like a pair of binoculars…. Models provide rules of inference through which new relations are discovered, and provide suggestions about how the scope of the theory can be increased.

(1970, p. 120)

The most important feature of meta-theories is that they are sets of assumptions that are often hidden from our own awareness. They help us as scientists, but they also create a filter that forces us to “see through a glass darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12). The first step in recognizing our own assumptive worldviews is to understand what meta-theories are, to become familiar with the kinds of assumptions they contain, and to note the different families of theories that are derived from them.

What is a meta-theory?

The assumptive worlds that underlie theories have been called by many names—“meta-theories,” “worldviews,” “world hypotheses,” “models,” “cosmologies,” or “paradigms,” as in “paradigm shifts.” Although they often seem to be more fitting for the realm of philosophers and discussions of philosophies of science, they penetrate our work as scientists. We use the term “meta-theory” because we like the image it creates. Meta means “above” or “beyond,” like “meta-physics,” and we like the image of a shadow or cloud hovering above all of our scientific activities.

What are meta-theories of human development?

Meta-theories in human development are sets of assumptions about the nature of humans and the meaning of development—what it looks like, how it happens, what causes it. Examples of meta-theoretical assumptions about human development would be the idea that all development ends at 18, or that aging is a process of loss and decline.

Why are meta-theories important?

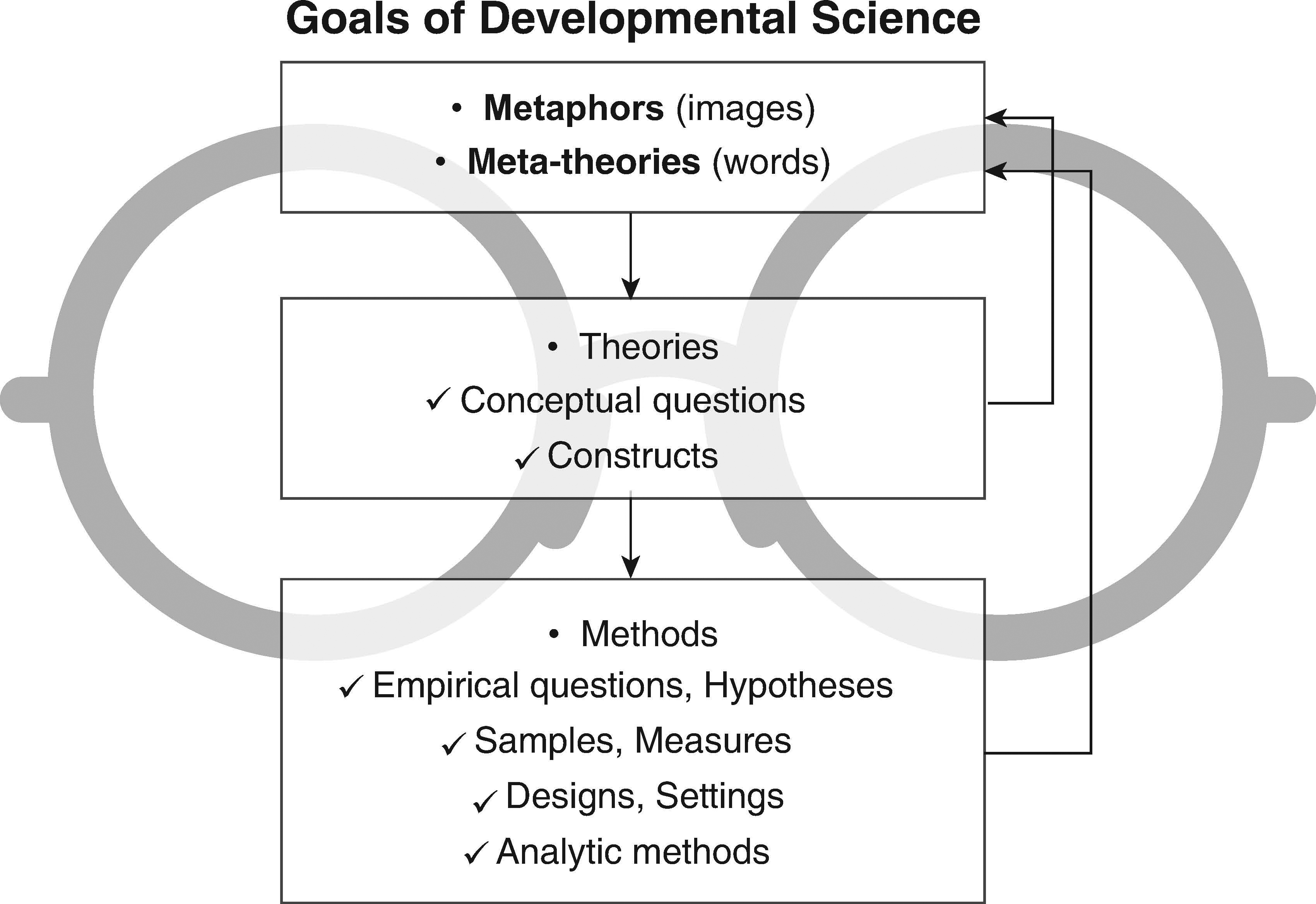

Meta-theories are important because their assumptions influence everything about how theories are constructed and research is conducted, including the questions that are asked, the measures and methods that are used, and how data are interpreted (see Figure 1.1.1). For example, if researchers assume that development ends at 18, they do not look for developmental changes after that age. Or, if researchers assume that aging is a process of decline, then they never look for characteristics that might improve as people get older.

What kinds of assumptions guide the study of human development?

Assumptions about humans and their development are both descriptive, in that they depict the nature of humans and what development looks like, and explanatory in that they explicate the causes of development (see Table 1.1.1).

|

Description 1. What is the nature of the person? 2. What is the nature of the environment? 3. What is the unit of analysis of change? 4. What is the course of development? Explanation 5. What is the role of the person in development? 6. What is the role of the environment in development? 7. What is the underlying hypothesized cause of development? |

Assumptions about Description

What are assumptions about human nature?

These refer to beliefs about the underlying qualities of our species—whether humans are born as blank slates (tabula rasa) or whether we all bring intrinsic human characteristics with us into the world. One of the most important of these assumptions centers on whether humans should be considered “active” or “reactive.” A “reactive” nature suggests that humans are inherently at rest, and so people tend to be relatively passive, unaware, and aimless. In contrast, an “active” nature suggests that humans are inherently and spontaneously active and energetic; that by nature all people are goal-directed, agentic, self-regulating, conscious, and reflective beings. For example, these different assumptions are readily apparent in alternative conceptualizations of motivation—some theories assume that motives and motivation are acquired, whereas others assume that all humans come with intrinsic motivations.

What are assumptions about the nature of the environment?

Descriptive assumptions apply not only to humans, but also to the nature of the environments they inhabit, for example, whether these surroundings are considered to be “active” or “passive.” “Active” environments have their own goals and agendas, and so busily work at shaping the developing person in specific desired directions. “Passive” environments, in contrast, have no particular agenda for the individual’s development, and so are not goal-directed in their interactions with the developing person. For example, in school contexts, teachers—who have an agenda and goals for their students—can be considered “active” environments, whereas students’ peer groups, while also important, may be more “passive” academic contexts, in that they typically do not have an agenda for the educational development of their members.

What are assumptions about the “unit of analysis of change”?

Perhaps the most basic of our descriptive assumptions entails our beliefs about the nature of the entities we are targeting in our developmental theories and research. Our choice of “units of analysis” or “focal objects” reveals our beliefs about where the developmental action is located. These assumptions are visible in each theory’s and each study’s choice of its “target phenomenon.” Some meta-theories assume that the most important entities to study are the fundamental building blocks that make up humans, such as their genes and their related phenotypic expressions, or human neurophysiological structures (like the brain), or stable traits and attributes (like intelligence, temperament, or personality). Other meta-theories focus their attention on observable behaviors and responses. Others insist that the key developing entities that deserve our attention are biopsychological structures and their functions in regulating actions. Yet others suggest that the fundamental units to consider are the interactions between the person and the context.

In analyzing these assumptions, the first step is to note the “bull’s-eye” that theories and studies consider the focal point of their activities. However, it is equally important to notice what these theories dismiss as irrelevant, as evidenced in their decisions about what not to include in theories and what not to study. For example, all theories of parenting focus on the role of parents in shaping children’s development, but only a subset of them also consider the forces that shape parent behavior. In a similar vein, all current theories of psychopathology typically include a place for the neurophysiological differences that underpin the manifestation of behavioral problems, but only a select few of these conceptualizations also consider the specific experiences that contribute to the development of those neurophysiological systems.

What are assumptions about the “course of development”?

These are the fundamental parameters that describe the way development proceeds. One of the most important features of the course of development, as shown already in Figure 1.1, is whether development involves quantitative continuous incremental change or discontinuous qualitative shifts (Overton & Reese, 1981). Some meta-theories assume that development is “more” or “less” of some characteristic, as reflected in descriptors like “trajectories” and the analysis of mean level changes or growth curves. Other meta-theories assume that development involves qualitative changes in the form, structure, or organization of a system, as reflected in descriptors like “phases,” “stages,” or “developmental tasks,” and the empirical search for age-graded shifts.

A second assumption about the course of development, also depicted in Figure 1.1, is whether pathways of development are presumed to be (1) normative and universal, meaning that all people pass through them in the same sequence, or (2) differential and specific, meaning that a variety of different patterns and pathways of developmental change are possible depending on the individual and the context. Sometimes assumptions about the course of development also refer to its directionality and presumed end state—whether development always refers to positive healthy growth and progression or whether it encompasses changes in many different directions, sometimes toward gains but sometimes toward declines, losses, or dysfunction.

Assumptions about Explanation

What are assumptions about the role of the person in development?

The causal role of the person in development generally involves two points that follow from a view of people as “active” versus “reactive” in their own development. A “reactive” model assumes that stability is the natural state of affairs, and that development is something that primarily happens to people—based on their genetic or environmental programming. And it is these factors, external to the agentic self, that instigate change, and to which people passively react. Sometimes this also implies that genetics, traits, characteristics, and experiences early in life can have permanent irreversible effects. In contrast, an “active” model assumes that the essence of substance is activity, meaning that the natural state of affairs is continuous transition or change. From this perspective, development is something in which people participate directly as active agents, choosing and shaping their own development. Sometimes this also implies that people are malleable and remain open to change throughout life.

What are assumptions about the role of the environment in development?

Assumptions about the causal role of the environment specify what is “on the arrows” from environments to the development of a target person. A view of the environment as “passive background” suggests that it operates only to provide the fuel needed to spur development from the inside (e.g., by providing nutrition for consumption and digestion, leading to growth). A more “active” environment is one that supports intrinsic motivations and growth tendencies by providing developmental affordances, that is, by essentially handing the organism what it intrinsically needs for the next steps in its development. Even more active are environments that support intrinsic motivations but also introduce their own socialization agenda through processes such as attunement and apprenticeship. Most active are environments assumed to be “running the show,” in that they are considered external forces that actively instigate, motivate, and shape growth from the outside.

What are assumptions about the underlying causes of development?

Most people have heard of these assumptions—these are the ones that usher in our favorite debates—nature versus nurture, heredity versus environment, genes versus experience, maturation versus learning, biology versus society, preformed versus epigenetic, innate versus acquired, nativist versus empiricist, and so on. Some meta-theories emphasize one over the other of these poles, and some are more toward the middle—that is, they insist on “and” formulations that emphasize the importance of both organism and environment. If you are interested in reflecting a bit about your own assumptions, we have included a set of questions in Table 1.1.2 about the nature of humans and their development. Your answers to these questions may reveal which way you are currently leaning on these issues.

| True? | False? | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| What is the Nature of Human Nature? | |||

| 1. | Humans are naturally selfish and self-interested. | ||

| 2. | Human beings are naturally active curious creatures. | ||

| 3. | Humans arrive as “blank slates” with no inherent characteristics. | ||

| 4. | At birth, people’s personalities are already determined. | ||

| 5. | At birth, all people have the potential to develop in any direction, positive or negative. | ||

| 6. | Human beings are predisposed to both good and bad behavior. | ||

| Nature or Nurture? | |||

| 7. | It’s mostly biology—genetics and maturation—that shapes human nature and development. | ||

| 8. | It’s mostly environment—families and society—that shapes human nature and development. | ||

| 9. | Genetic and environmental factors shape human nature and development equally. | ||

| Active or Reactive? | |||

| 10. | People’s development is a product of forces outside their own control. | ||

| 11. | People are actively engaged in their own growth and development. | ||

| 12. | People are mostly reactive and are molded by other people and their environments. | ||

| 13. | People actively choose and shape themselves and their environments, and are shaped by their environments in equal measure. | ||

| Stability or Change? | |||

| 14. | Traits and experiences early in life have a permanent effect on people’s development. | ||

| 15. | People are malleable and can be changed by their environments and experiences at any age. | ||

| 16. | People are malleable and can change themselves at any age. | ||

| Continuity or Discontinuity? | |||

| 17. | Humans develop gradually through incremental changes, moment by moment, bit by bit, day by day. | ||

| 18. | Humans develop in fits and spurts over a lifetime through qualitative stages of growth. | ||

| 19. | Humans develop continuously day by day as well as through stage-like progressions over a lifetime. | ||

| Universal or Context Specific? | |||

| 20. | There are universal stages we all go through, from infancy to childhood to adolescence to adulthood. | ||

| 21. | An individual’s pathway of development depends on that person’s specific culture and combination of experiences. | ||

References

Bijou, S. W., & Baer, D. M. (1961). Child development: Vol. 1. A systematic and empirical theory. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Brainerd, C. J. (1972). Neo-Piagetian training experiments revisited: Is there any support for the cognitive-developmental stage hypothesis? Cognition, 2(3), 349–370.

Cairns, R. B., & Cairns, B. (2006). The making of developmental psychology. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Theoretical models of human development: Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., Vol.1, pp. 89–165). W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Editors-in-Chief). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Deci, E. L. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. New York, NY: Plenum.

Flavell, J. H. (1963). The developmental psychology of Jean Piaget. Princeton, NJ: van Nostrand.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Overton, W. F., & Reese, H. W. (1973). Models of development: Methodological implications. In J. R. Nesselroade & H. W. Reese (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Methodological issues (pp. 65–86). Oxford: Academic Press.

Overton, W. F., & Reese, H. W. (1981). Conceptual prerequisites for an understanding of stability-change and continuity-discontinuity. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 4(1), 99–123.

Pepper, S. C. (1942). World hypotheses. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Reese, H., & Overton, W. (1970). Models and theories of development. In L. R. Goulet & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), Lifespan developmental psychology (pp. 115–145). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Strauss, S. (1972). Inducing cognitive development and learning: A review of short-term training experiments I. The organismic developmental approach. Cognition, 1(4), 329–357.

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66, 297–333.