1 Laying the Foundation

Introduction

This chapter begins with a short journey through the history of grammar study. We review the different senses of the term grammar and clarify what the term means when used in this textbook. We discuss how prescriptive grammar differs from descriptive grammar, and we introduce acceptability judgments as an analytical tool for uncovering the organizing principles of English sentence structure. The discussion acknowledges the presence of syntactic variation in present-day American English and explains the textbook’s approach in addressing it. Next are tips for combatting grammar anxiety for readers who may be experiencing it. The chapter closes with a preview of the fruits of the labor involved in mastering sentence analysis, specifically becoming more knowledgeable and deliberate in your choices as a writer as well as more perceptive as a student of literature.

Chapter Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to

- Differentiate between prescriptive and descriptive grammar study and grammar rules.

- Report grammatical acceptability judgments.

- Appreciate how gaining masterful control of the structure of English empowers us to make intentional choices when crafting sentences.

- Practice methods for combatting grammar anxiety.

Overarching Goal

The general aim of this textbook is to describe the grammar of English to a diverse audience of students, including future educators, aspiring authors, budding linguists, and curious linguaphiles. The overarching goal is to help readers build grammar awareness and knowledge in order to accomplish the following types of tasks with confidence:

- Make intentional grammatical choices when writing.

- Identify available grammatical alternatives and their effect on meaning.

- Understand how a writer’s grammatical choices contribute to meaning.

- Identify and correct ungrammatical or inappropriate choices.

- Assess the grammatical complexity of a text.

- Identify specific grammatical challenges of students in your own teaching practice.

- Evaluate and select appropriate grammar learning materials for use in your own teaching practice.

- Adapt grammar learning materials to diverse learner needs and contexts.

- Devise effective instructional tasks for use in your own teaching practice.

- Analyze the grammatical structure of authentic language.

Approaches to Grammar Study

To situate this textbook in the rather long tradition of grammar study, we begin with a discussion of two distinct approaches to the task. One approach is prescriptive in nature. It prescribes how speakers and writers of a language should use it to be deemed correct. The second approach is descriptive in nature. It describes the structure of a language as it is actually used by its native speakers without passing any judgment. To a descriptive grammarian, the term grammar refers to the rules and principles native speakers have acquired naturally from birth—that is, the grammatical knowledge in the minds of native speakers to which linguists refer as mental grammar.

Prescriptive Grammar

Prescriptivism in grammar study involves establishing rules which dictate how words and sentences should be structured and used by writers and speakers of a language. This approach is rooted in the tradition of documenting and recording classical languages to ensure subsequent generations can read and understand ancient historical documents. In the case of English, prescriptivism emerged in the 18th century in a climate of significant language variation among speakers of the language. Calls for the establishment of an English academy to standardize and regulate the use of the language to foster and ensure mutual intelligibility were met with resistance in both the United Kingdom and the United States. However, even in the absence of an English academy, prescriptivism still flourished through the publication of several independent authoritative English grammars and dictionaries, whose authors advanced their personal views on correct and proper usage. Popular and most influential among them were A Dictionary of the English Language by Dr. Samuel Johnson, published in 1755;[1] the Short Introduction to Grammar by Bishop Robert Lowth, published in 1762;[2] and English Grammar by Lindley Murray, published in 1795.[3] Today, prescriptivism is the foundation of grammar manuals and style guides published by authoritative bodies, such as the University of Chicago (Chicago Manual of Style), the Modern Language Association (The MLA Style Manual), the American Psychological Association (APA Style), and the Associated Press (AP Stylebook). Pedagogical grammar books are typically prescriptive in nature.

Various aspects of the language are targeted by prescriptivists, including pronunciation, word choice, verb forms, negation, sentence structure, and, in the case of written language, word spelling and punctuation. Generally, language prescriptivists refer to preferred forms of the language as “correct” or “proper” and to dispreferred forms as “incorrect” or “bad.” Prescriptive rules take the form of statements that dictate which sentence structures or word forms to use and which to avoid, as the following examples illustrate:

- Never omit the relative pronoun in a relative clause.

- Never end a sentence with a preposition.

- Never split an infinitive.

- Never use two negatives in the same sentence.

- Never start a sentence with And or But.

- When forming the simple future tense, use the auxiliary verb shall with a first-person subject, and use the auxiliary verb will with second- and third-person subjects.

Descriptive Grammar

The second approach to grammar study is descriptive. It aims to provide an objective and nonjudgmental description of the grammatical constructions in a language. The term grammatical in this framework applies to all the language structures that conform to the structural rules of the language present in the minds of its fluent native speakers. In other words, descriptive grammar refers to the set of constraints that fluent native speakers of a language abide by when composing words, phrases, clauses, and sentences in their language.

Within a descriptive grammar framework, one methodology linguists often rely on is the acceptability judgment test. Also known as acceptability judgment task or acceptability rating task, this is an empirical task in which fluent native speakers of a language are shown a sentence and asked to indicate as quickly as possible whether a sentence sounds structurally acceptable to them. Take, as an example, the string of words The cat stretched on the sofa. Does this string of words sound structurally acceptable to you as a well-formed English sentence? The answer is yes, so the string passes the acceptability judgment test and is grammatically accurate. By contrast, consider the string of words Cat the on stretched the sofa. Does this same set of words in this order also pass the acceptability judgment test? The answer is no, so it serves as evidence of an unacceptable English sentence structure. You may be thinking at this juncture that the difference between these two strings of words is that one sentence makes sense whereas the other doesn’t, and you are correct. However, notice that you would also accept the string of words Colorless green ideas sleep furiously as a structurally grammatical English sentence, yet it, too, makes no sense. The acceptability of this nonsensical sentence, proposed by Noam Chomsky in Syntactic Structures, illustrates that the acceptability judgment task can be used to tap into native speaker knowledge of grammatical sentence structure regardless of sentence meaning.[4]

Activity 1.1

Differentiating Descriptive from Prescriptive Grammar

Differentiating between the two approaches can be tricky because they share common ground. They rely on much of the same grammatical terminology, and they make similar distinctions among grammatical categories of words and structures. To confuse things further, both approaches refer to rules. However, the tone of descriptive rules is significantly different from the tone of prescriptive rules. To illustrate, compare the following two observations about the structure of the utterance Try and get here early in contrast to Try to get here early. You will have no trouble identifying the prescriptive one in contrast to the descriptive one:

- The verb try requires an infinitive as its complement—for example, try to go, try to remember. Never use and in place of to following the verb try.

- The verb try is both transitive and intransitive. When used as a transitive verb, it takes an infinite as its complement, as in I will try to remember this. As an intransitive verb, it is used alone, as in I promise to try, and as the first verb in a compound verb phrase, as in I will try and remember this. In formal contexts, try is predominantly used as a transitive verb followed by an infinitive.

The first rule is prescriptive. Prescriptivism is present when a grammatical explanation insists on adhering to traditional and well-established guidelines of grammar use. This approach characterizes language use recommendations by teachers, parents, writing coaches, editors, and so on, including editing software. The second rule is descriptive. It provides a grammatical explanation for the observed variants in the use of the verb try, and it describes the distribution of the two variants in terms of their formality.

Let’s look at one more example. Some speakers of American English produce the following constructions: That might could work. We might should go to the store. My editing software underlined the double modals and proposed deleting might—it is being prescriptive. From a descriptive vantage point, the combination of might with could is an acceptable structure in the mental grammar of the native speakers who use it, and as a descriptive linguist, my job is to determine the acceptable combinations of different modal auxiliary verbs, the meanings associated with the acceptable combinations, and their distribution across different varieties of English and different levels of formality.

Activity 1.2

Scope

Narrowing down the scope of a book on the structure of English is no easy task. Not only is English a language with a long history, but it is also a language with a wide reach. Additionally, even within each English-speaking country or region, such as North America, we find grammatical variation among the active dialects as well as between the formal and informal forms of the mainstream variety. For example, several varieties of American English (AmE) allow the combination of multiple modal auxiliary verbs in succession to introduce separate modalities in a sentence, as in I might can go to the party, but the mainstream variety does not. Similarly, whereas I gotta go is a structure within the grammar of the informal mainstream variety of AmE, it is absent from the grammar of the formal mainstream variety. It is helpful in discussions of the grammar of AmE to draw the following global distinctions among varieties, all of which can be reflected in both speaking and writing:

- Formal Mainstream American English: The variety used in formal situations, taught in U.S. schools, and characterized by norms which are prescribed by sources of authority, such as usage manuals and style guides. The written version is also labeled Edited American English, Academic English, or Standard Written English.

- Informal Mainstream American English: The variety used in informal situations and characterized by the absence of socially stigmatized linguistic forms and structures.

- Vernacular American English: All the varieties which differ from the mainstream variety and are characterized by the presence of some socially stigmatized linguistic forms and structures.

A second hurdle is narrowing down the structural components of English to be described. Notice that a fluent speaker of the language has multiple levels of knowledge regarding its structure. First is the knowledge of English speech sounds and the rules governing their co-occurrence. For example, you know that glorp could be an English word, whereas rlogp could not. Second is the knowledge of rules governing English word structure. For example, you know that happy is grammatically related to happier, and you also know that while happier is a well-formed English word, erhappy is not. You also know that the –er in happier is not the –er in shopper. In more formal terms, you know that the –er in happier is an inflectional suffix, which combines with adjective and adverb roots to create their comparative form in English. By contrast, the –er in shopper is a derivational suffix, which attaches to a verb to create a noun meaning ‘person engaged in the activity indicated by the verb’. Third is your knowledge of English sentence structure. For example, you know that He likes candy is a grammatical English sentence, whereas Candy likes he, Likes he candy, and Likes candy he are not.

A third concern when determining the scope of an English grammar textbook is ensuring it addresses the needs of all its readers. This textbook is aimed at a diverse population of students of English grammar, and your individual needs will differ, at least to some extent. Those of you becoming English teachers should ideally be presented with the opportunity to master all the grammar terms you will likely encounter in your teaching career and, if possible, to learn how to best incorporate grammar instruction and assessment into your own classes. Those of you becoming professional writers would ideally master the structure of English well enough to feel in control of the language as a writer. Those of you interested in teaching English to nonnative speakers would benefit from a textbook which describes the structure of English in relation to the alternative grammatical structures of the languages spoken by your students. Finally, some of you may want a review of the prescriptive rules and conventions associated with formal writing.

Overview

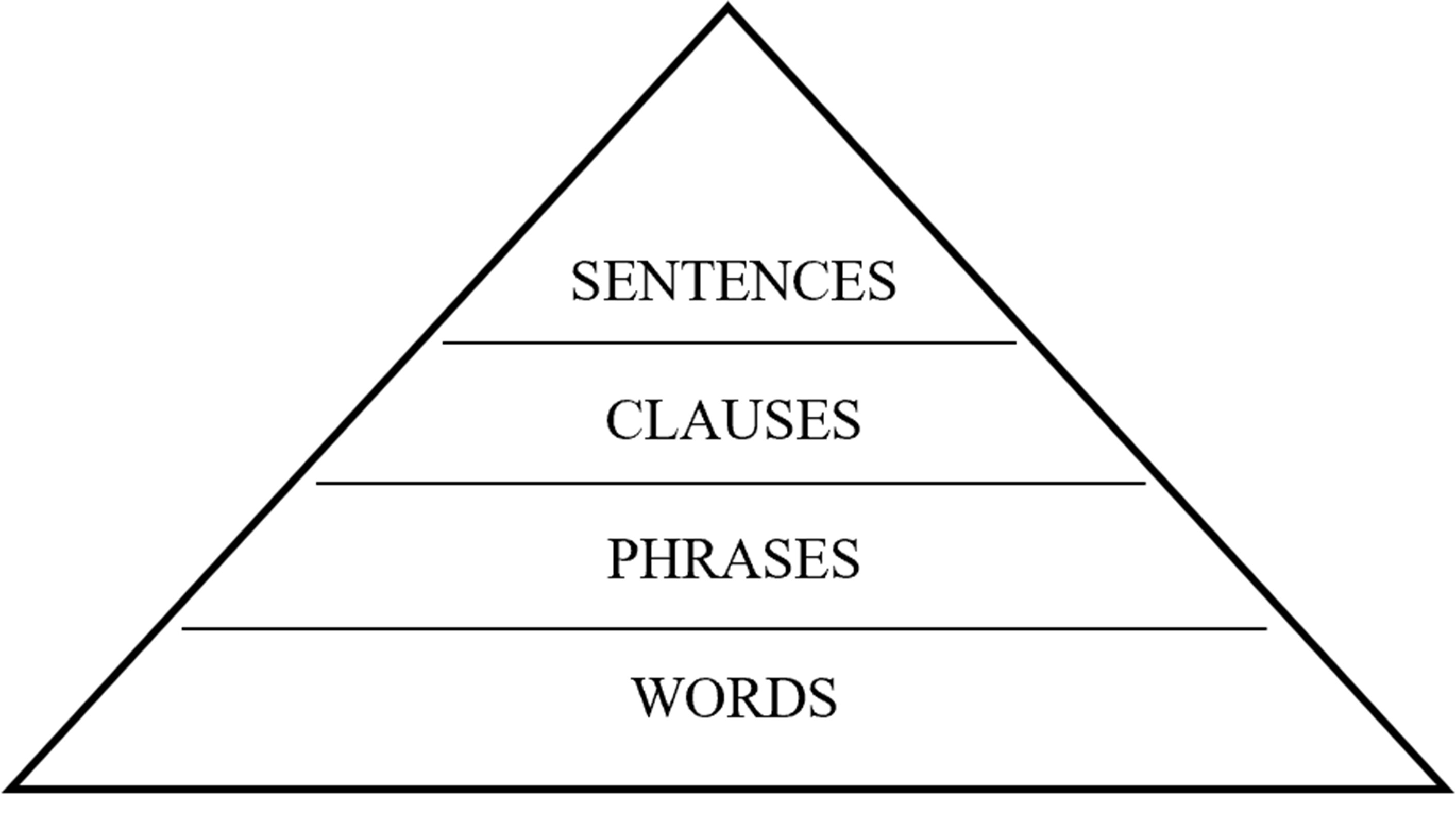

To achieve its goals, this textbook provides a review of English grammar with a primary focus on the Formal Mainstream American English variety and a secondary focus on areas of syntactic variation among varieties of Vernacular American English. The textbook is organized in two parts. Unit I consists of eight chapters, whose goal is to provide readers with an understanding of the role of each level of structure (shown in Figure 1.1) in the construction of English sentences.

Chapter 2 reviews the open categories of words. Chapter 3 is a survey of the closed categories of words. Chapter 4 introduces the structural level of the phrase and introduces analytical tools for identifying and labeling different types of phrases. Chapter 5 addresses the structural level of the clause with a focus on the role of verbs in clause structure. Chapter 6 examines how we manipulate the structure of clauses to perform different discourse functions, and we look in detail at the structural properties of declarative, imperative, interrogative, and exclamative clauses. Chapter 7 reviews the structure of simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences. Chapter 8 connects the dots by discussing form in contrast to function.

Unit II dives more deeply into the grammar of English verbs. We review tense and aspect in chapter 9, voice and mood in Chapter 10, and negation in chapter 11. Chapter 12 addresses grammatical variation in dialects of American English.

Grammar Anxiety

I have included a section on grammar anxiety for two reasons. First, some of you may have experienced it. Second, even if you don’t have grammar anxiety yourself, if you plan to teach English, you will likely teach students who do, and you may find the suggestions here valuable. Third, if you struggle with writer’s block, the advice in this section might prove helpful to you, as well. Even if none of these scenarios apply to you, you may still find it valuable to explore your own beliefs about grammar as you embark on this journey.

While writing this textbook, I was mindful of the apprehension some of you may experience in relation to learning grammar. I have tried to do my part in helping you learn without experiencing anxiety. I have attempted to pace the introduction of new terms and concepts, incorporated examples to adequately illustrate terms and analytical methodologies, and created interactive activities to give you opportunities to practice what you learn and assess your progress toward mastery. You must also do your part to combat any anxiety you may experience. Read deliberately. Every word serves a purpose. Reread any sentences, paragraphs, or sections that leave you confused. Be sure to complete the embedded interactive exercises to gauge your understanding. Treat mistakes as learning opportunities, and revisit the relevant explanations and examples until you feel more confident in your understanding before proceeding to the next section or completing the end-of-chapter graded activities. Before proceeding to the next chapter, keep in mind that subsequent chapters assume knowledge of the grammatical phenomena and terminology presented in earlier chapters. Avoid reading selectively or skipping around. If you have experienced grammar anxiety in the past, it would be helpful to identify the root of your anxiety and consider some of the following suggestions to overcome it.

Several factors are known to contribute to grammar anxiety. One major factor is the presence of negative past experiences associated with grammar learning, ranging from struggling to understand a grammar topic to possibly even being told by any authority figure that you are not good at grammar. If you harbor some such negative memories, you may want to consider the following strategy which is particularly effective in reframing a negative memory to your advantage. Doing so is valuable because persistent recall of negative memories is known to increase anxiety. Start by recollecting your negative memories associated with grammar learning. For each of the negative memories you retrieve, complete the following task: Think of something you learned or something positive that you gained from the incident. Focus specifically on the positive aspects of this memory. How could you reframe the negative memory by focusing on its bright side? How can it become valuable to you in some way? For example, you may have a negative memory associated with earning a low grade on an examination, and by focusing on the positive, you can reframe this memory as an incident that taught you to study more effectively when preparing for exams going forward. Repeat this strategy with as many of your negative memories associated with grammar learning as you can recall. Changing how you think about these incidents will change how you feel about grammar learning, so you can engage with the grammar knowledge in this textbook unimpeded.

The second major factor associated with grammar anxiety is a learner’s belief system about grammar. In some cases, early negative experiences associated with grammar learning lead to negative beliefs about grammar. However, even in the absence of negative memories attached to grammar, one may hold negative or inaccurate beliefs about grammar knowledge, instruction, assessment, learner aptitude, and the value of learning grammar. The following are examples of such beliefs:

- Grammar is a set of confusing rules that people can’t even agree on.

- Grammar is a list of rules that must be memorized, and my memory isn’t great; memorization is the obstacle to my learning grammar.

- Grammar is a matter of arbitrary pronouncements that define “good’” vs. “bad language; it is pointless to learn them because they change unpredictably, or they are not relevant outside of academic contexts, or both.

- English grammar has numerous, variable, inconsistent, vague, rigidly soft “rules.”

- English has too many irregularities and inconsistencies, and its grammar is too complicated.

- Learning grammar is not necessary for me to achieve my life goals.

- I am not good at learning grammar.

These beliefs are not only negative, but several are also inaccurate. If left unchallenged, they create unnecessary stumbling blocks in one’s effort to master English grammar. Notice how vastly different they are from my own beliefs about grammar.

The Author’s Beliefs About Grammar

- Learning grammar involves discovering the constraints that apply to different aspects of the grammar system of a language by closely examining language samples and by relying on native speaker intuitions.

- Discovering the rules governing a grammatical phenomenon by analyzing language data is enjoyable in the same way that solving puzzles is fun.

- Learning the various terms that apply to grammatical forms and functions does not require a strong memory, only time and practice.

- Knowing grammatical terminology enables us to discuss grammar with others using common language.

- Mastering a variety of grammatical constructions makes the craft of writing interesting, fun, and personally rewarding.

- Punctuation norms align with structural aspects of English in logical and predictable ways.

- Mastering punctuation norms ensures my readers will comprehend my writing and my efforts will be worthwhile.

- Anyone with a desire to learn grammar can learn grammar.

While your beliefs about grammar will differ from mine, replacing any negative beliefs you hold with positive beliefs which ring true to you will help pave the way toward a positive experience studying English grammar. Additionally, this textbook will provide you with the necessary knowledge about the structure of English to help you reframe any inaccurate beliefs you may currently hold about the nature of the grammar of English and the experience of studying it.

The Author’s Craft

Most chapters in this textbook include a section devoted to the author’s craft with a focus on sentence structure. Based on my own experience as a writer, I strongly believe that gaining masterful control of English grammar empowers us to make intentional choices when crafting sentences. Naturally, vocabulary knowledge is an important prerequisite. However, so is knowledge of the structural possibilities the language affords us when combining our words to create sentences. In this chapter, we will look at two examples of this knowledge at work.

The first example is from Little Women by Louisa May Alcott.[5] The novel is loosely based on the lives of the author and her three sisters. In this section, she introduces the four main characters, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Notice the variety of syntactic structures Alcott enlists to create a fresh start for each of the sisters as her description moves from one to the next. Notice that to keep our interest in this long, descriptive passage, Alcott does not rely on snazzy word choice. Instead, she introduces structural intricacy at the sentence level. Most striking is the structure of the underlined clause in the middle of the paragraph, where Alcott breaks the flow by swapping the typical subject–verb–object order (Joe had round shoulders) for the highly uncommon object-–verb–subject order (Round shoulders had Jo):

Margaret, the eldest of the four, was sixteen, and very pretty, being plump and fair, with large eyes, plenty of soft brown hair, a sweet mouth, and white hands, of which she was rather vain. Fifteen-year-old Jo was very tall, thin, and brown, and reminded one of a colt, for she never seemed to know what to do with her long limbs, which were very much in her way. She had a decided mouth, a comical nose, and sharp, gray eyes, which appeared to see everything, and were by turns fierce, funny, or thoughtful. Her long, thick hair was her one beauty, but it was usually bundled into a net, to be out of her way. Round shoulders had Jo, big hands and feet, a flyaway look to her clothes, and the uncomfortable appearance of a girl who was rapidly shooting up into a woman and didn’t like it. Elizabeth, or Beth, as everyone called her, was a rosy, smooth-haired, bright-eyed girl of thirteen, with a shy manner, a timid voice, and a peaceful expression which was seldom disturbed. Her father called her ‘Little Miss Tranquility’, and the name suited her excellently, for she seemed to live in a happy world of her own, only venturing out to meet the few whom she trusted and loved. Amy, though the youngest, was a most important person, in her own opinion at least. A regular snow maiden, with blue eyes, and yellow hair curling on her shoulders, pale and slender, and always carrying herself like a young lady mindful of her manners. What the characters of the four sisters were we will leave to be found out.

The second example is from Gather Together in My Name by Maya Angelou.[6] It is the second volume in the author’s autobiographical series. As you read this passage, notice the structure of the underlined sentences:

By no amount of agile exercising of a wishful imagination could my mother have been called lenient. Generous she was; indulgent, never. Kind, yes; permissive, never. In her world, people she accepted paddled their own canoes, pulled their own weight, put their own shoulders to their own plows and pushed like hell, and here I was in her house, refusing to go back to school. Not giving a thought to marriage (admittedly, no one asked me) and working at nothing. At no time did she advise me to seek work. At least not in words. But the strain of her nights at the pinochle table, the responsibility of the huge sums which were kept in the bedroom closet, wore on her already short temper.

This paragraph is composed of eight sentences describing Maya Angelou’s mother. Notice that Angelou went to some lengths to ensure that not a single sentence begins with the words my mother or she. Even in the underlined sentences, Angelou does not rely on a prototypical word order, such as My mother could not have been called lenient by any amount of agile exercising of a wishful imagination; She was generous; and She did not advise me to seek work at any time. Instead, Angelou tucks the words my mother and she in the middle of each of these three sentences by recruiting alternative grammatical sentence structures.

As you can see from these examples, deep knowledge of sentence structure allows a writer to flex their writing muscles, and this applies to both fiction and nonfiction writing. Take, for example, my first sentence in this section of this chapter. It reads Narrowing down the scope of a book on the structure English is no easy task. I could have written It is no easy task to narrow down the scope of a book on the structure of English, or It is not an easy task to narrow down the scope of a book on the structure of English, or It is a difficult task to narrow down the scope of a book on the structure of English, or Narrowing down the scope of a book on the structure of English is a difficult task, or Narrowing down the scope of a book on the structure of English is not an easy task. I intentionally crafted this sentence to be Narrowing down the scope of a book on the structure of English is no easy task. Here is why. My main goal in this section of the book is to explain how I narrowed down the book’s scope. Starting with the words narrowing down brings this goal into clear focus immediately. Next, I chose the predicate is no easy task as opposed to is not an easy task, and I chose to avoid the word difficult. While the task is not straightforward, it is not difficult, and it is, in fact, a task, so I chose is rather than is not. Clearly, a lot of thought and time went into that single sentence, and you may wonder how realistic or beneficial it is to devote this much effort to crafting individual sentences, let alone paragraphs of sentences. I believe it is both realistic and beneficial. With practice, one can master manipulating the order and placement of elements in sentences for rhetorical effect, and one becomes faster with experience. Ultimately, writing becomes more fun for the author, and the fruits of their labor are more engaging and far less ambiguous to readers. What would be the point of writing sentences that readers were unwilling to read because they put them to sleep or confused them?

Looking Ahead

As you embark on your journey across the grammatical landscape of American English sentence structure, remember the following:

- This textbook provides a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, overview of mainstream American English.

- It is valuable to reflect on your own belief system about grammar as well as any feelings of anxiety associated with grammar study so that these do not interfere with your grammar journey.

- The more you master the intricacies of the grammatical system of English, the better a writer you can become.

Reflection Questions

- Acceptability judgment tests are widely used in empirical linguistics as a method to describe the mental grammar of speakers of a language. As a competent English speaker, you can readily distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable cases; however, you are able to make even finer distinctions. To prove this point, provide one example sentence to illustrate the following types of acceptability judgments.

- A sentence that no speaker of English would ever produce and which no native speaker of English would judge acceptable, under any circumstances. This type of sentence fails the acceptability judgment test because it violates the descriptive rules of English.

- A sentence that conforms structurally with the descriptive rules of English but is nonsensical.

- A sentence that conforms with the mental grammar of a native English speaker but breaks at least one prescriptive grammar rule.

- An English sentence most native speakers of American English would deem acceptable to use but only in informal interactions.

- An English sentence that most native speakers of American English would deem acceptable to use in all contexts, including formal or professional settings.

- Write five English sentences that reflect five grammatical “errors” based on your personal judgment. These sentences must pass the strictest acceptability judgment test—that is, all would be judged grammatical to use in some context by at least one native speaker of English. Share your list of sentences with five native speakers of American English, and ask them to evaluate the grammaticality of each sentence and to identify any “errors” in their judgment. Discuss your findings. What was the consensus regarding each “error,” and how would you order these “errors” in terms of gravity based on this small sample?

- Select an educational context in which English grammar is typically taught. If you plan to become a teacher of English yourself, choose the context in which you plan to do so. In that context, how might the two approaches to grammar study serve the needs of students? How would the differences between these approaches inform your own curriculum and instruction?

- In an interview, Claudia Tate asked Maya Angelou what she thought her responsibility was as a writer, to which Angelou replied the following:

My responsibility as a writer is to be as good as I can be at my craft. So I study my craft. I don’t simply write what I feel, let it all hang out. That’s baloney. That’s no craft at all. Learning the craft, understanding what language can do, gaining control of the language, enables one to make people weak, make them laugh, even make them go to war. You can do this by learning how to harness the power of the word. So studying my craft is one of my responsibilities.[7]

Can you think of a time when you found yourself harnessing the power of language in a way that ensured your message was effective in communicating your intent accurately? What was the context, and how exactly did you attempt to “gain control of the language”?

- Many people feel insecure about their ability to write in ways that satisfy their readers’ expectations. Grammar anxiety is, therefore, quite common, and it can lead to writer’s block. If you have successfully overcome grammar anxiety when writing, describe the method(s) you have relied on. If you currently struggle with grammar anxiety, choose a method to combat your anxiety, practice using it, and report your impressions. You can practice a method introduced in this chapter, or you may select a suggestion from another published source on the topic.

- Johnson, S. (1755). A dictionary of the English language: In which the words are deduced from their originals, and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. To which are prefixed, a history of the language, an an English grammar. W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, et al. ↵

- Lowth, R. (1762). A short introduction to English grammar: With critical notes. J. Dodsley and T. Cadell. ↵

- Murray, L. (1795). English grammar, adapted to the different classes of learners. With an appendix containing rules and observations, for assisting the more advanced students to write with perspicuity and accuracy. Wilson, Spence & Mawman. ↵

- Chomksy, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. Mouton. ↵

- Alcott, L. M. (1868). Little women, or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Roberts Brothers. ↵

- Angelou, M. (1974). Gather together in my name. Random House. ↵

- Tate, C., & Angelou, M. (1985). Black women writers at work. Oldcastle Books, Ltd. ↵