2 Chapter 1: What Is Literacy?

Chapter 1

What is literacy? Take a moment to think about how you would define literacy. Most people define literacy by a person’s ability to read and write. While this is the most common and popular way to define literacy, literacy goes beyond just reading and writing (Guerra, 1998). Most of us think about learning how to read and write in school, but literacy really begins at home (Morrow, 2001). Over the decades of schooling in the United States, researchers and policymakers have examined reading instruction very closely (National Reading Panel et al., 2000). Reading tests have been used to measure students, teachers, and schools. Literacy and reading are not necessarily the same thing. In our tutoring program, we highlight the idea of literacy—not just the skill of reading. It will be imperative for you to understand the difference.

Purpose of the Chapter

Literacy is a complex topic. This chapter is designed to provide you with background information about how literacy is defined, what theories are used to describe literacy, and what literacies students bring to tutoring. Literacy includes understanding a topic in depth, demonstrated by the ability to engage in activities related to the topic, being able to talk about or explain the topic, or being able to modify and improve their knowledge of the topic at a high level (e.g., financial literacy, civic literacy). Think about a topic you know very well. You may have personal experiences and background knowledge related to the topic. For example, a shrimper has specific knowledge of their craft. Their knowledge of the Gulf waters, the weather, and the shrimp, fish, and oysters they gather is in-depth. Yes, they can probably read and write and use these skills when they work, but they also have the ability to “read” the weather and water, to know what time of day to head out on the boat, what time of year to fish for flounder, and when to harvest oysters. They are able to analyze laws and legislation that regulate fishing. They can articulate their knowledge by breaking down ideas and explaining them to others, demonstrating how to prepare the boat, how to fish, and what the signs of the weather and water meant. They are highly literate in fishing and shrimping. On the other hand, others may not be literate in fishing. While they can see if the sky is sunny or cloudy, they cannot tell what that means for fishing that day. They can read a book on how to prepare a boat for the water but cannot actually walk up to a boat and know how to interpret what they see. All of us have literacies related to our lives. Students bring their literacies to us, and we must recognize and use them as we build their reading and writing abilities.

Literacy involves knowing about particular topics in-depth. Someone may have a PhD in literacy, but they may not be literate in many areas such as astronomy or taxes. They may be able to read the instructions on their tax return and try to answer each question, but they may not really understand deeply what the questions mean and seek out a professional tax accountant for assistance because this individual is highly literate in current tax laws and can interpret the tax forms. This does not mean that someone cannot read, but it does show how literacy is more than just reading words on a page. We want you to keep this in mind as you tutor. Before you read the chapter, please take a moment to answer the pre-reading questions that follow. Record your answers so when you are done reading you can go back and review what you have learned. Definitions for each term are both in the text and in the glossary.

How would you define literacy?

What literacies do you possess?

How is literacy used by students in their daily lives?

The following terms will be crucial for you to understand as you move into learning how to tutor students.

Developmental level

Funds of knowledge

Literacy

Multimodal

Understanding these key terms will help you as you learn about teaching your student. Our goal is to make sure you recognize the literacies that students bring to the tutoring sessions so you can build your teaching on their strengths. When students struggle with reading and writing, it helps to know what they are interested in and already know about. For example, if a student knows a lot about dinosaurs, you can build your reading and writing around dinosaurs. The following sections cover theories, developmental levels, types of literacy, and how forces in and outside of schools shape literacy for young students.

What Are Theories Related to Literacy?

Literacy

Literacy is a broad term that moves beyond simple reading and writing. Literacy includes in-depth knowledge about a topic and the ability to listen, speak, read, and write.

Theories are used to define literacy and provide a framework on how to teach literacy (Tracey & Morrow, 2012). While most of us do not talk about theories in our daily lives, we all have theories about how things work and how they should be done. Some people may theorize the best way to train a horse is to use behaviorism and give the horse treats for each command performed correctly. Others may follow a more natural approach and work with the animal’s natural behaviors to get the horse to do specific things. Theories guide our thinking. They give us ways to explain how and why we are doing a task in a particular way. We may or may not talk directly about our theories in scholarly terms, but they are there and meaningful for us. The same ideas are true for teaching literacy. Theories about literacy are based in research and provide ways to demonstrate and explain how children learn. There are many theories about how to teach students to read and write; some are focused on how to teach the broader ideas related to literacy while others emphasize learning skills such as the alphabet. There are no right or wrong theories; most good instruction uses many aspects of various theories. Each student is different, so the more approaches you can use, the more effective you will be. See Tracey and Morrow (2012) for a comprehensive look at the theories related to literacy. Some students need focused, direct instruction at times, and others may need a more student-centered type of lesson. In our tutoring program, we will present ideas that reflect many theories, but the theories we will most rely on will be (a) funds of knowledge (Gonzales et al., 2005), (b) developmental stages of reading development (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996), (c) multimodal literacies (Kress, 2002), and (d) psycholinguistic theory (Goodman, 1967; Smith, 1971). You do not have to memorize these ideas, but you do need to understand their basic components before you begin to tutor.

Thinking about literacy broadly and approaching your instruction from a literacy perspective—rather than from just a reading and writing view—means you will recognize the literacies students bring with them and work to build a bridge between what they know and what they need to know instead of just teaching a list of words and skills. The following sections describe the theories related to our views of tutoring.

What Are Literacies?

“Literacies” refer to all types of literacies students bring to us. As we mentioned earlier, there are many types of literacies when you look beyond just reading and writing. There is a tradition of categorizing people as literate or illiterate. We argue that everyone is literate, that literacy looks different for everyone, and that as teachers we recognize all literacies. It is important to recognize how we can understand a student’s strengths. In the example about the shrimper, you learned how his knowledge went beyond reading words on a page. There are many recognized literacies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2002). Termed multiple literacies, these literacies are identified as scientific literacy, civic literacy, financial literacy, and so on and represent ways to name different types of literacies in relation to specific types of knowledge. Each of these literacies is unique to the area it covers. For example, civic literacy refers to the knowledge and understanding of how to engage in civic life (Marciano, 1997). When we think of civic life, we may think of voting or community service. To be civically literate we do not necessarily need to be able to read and write; it is ideal, and we would never want someone to not be able to read and write, but it is not a requirement. Citizens can determine how they are going to vote by watching the news, going to town hall meetings, or talking with others to make informed decisions. Even in the earliest of democracies, oral discussion was the predominate mode of engaging in civic acts (Graff, 1987). Other literacies are just as specific and may not depend on just reading and writing. For our purposes, it is important to recognize these types of literacies to know what our students are bringing to our lessons so we can learn from the students and connect what they know to the printed words they need to be able to read and write. Although we focus on literacy broadly, we are also working with students to ensure they can read and write well. Relying on their existing knowledge can be an effective way to bring reading and writing to life for students.

Funds of Knowledge

Funds of Knowledge

Funds of knowledge stress the important knowledge students bring with them to instructional settings.

Funds of knowledge is a concept we will use often in tutoring. Related to multiple literacies, the notion of funds of knowledge stresses the important knowledge students bring with them to instructional settings (Gonzalez et al., 2005). Too often school settings are separated from the home lives of students, with educators expecting that students will conform to school expectations with little regard for their existing knowledge and abilities.

Funds of knowledge is based on research by Moll et al. (1992) in which the researchers went into students’ homes and brought family and student knowledge into the classroom. They found students were more engaged and learned more than when their knowledge was overlooked (Moll et al., 1992; Gonzalez & Moll, 2002). Students in tutoring programs are often not doing well in school. They may not be motivated to read and write or see how school connects to their own experiences. As you tutor you want to get to know your students and their families so you can build on what they know and see their strengths. We cover this in more detail in Chapter 3.

Multimodal Literacy

Multimodal Literacy

Multimodal literacy recognizes the various texts and modes we use today beyond just books.

Multimodal literacy recognizes the limitations of relying on books and pen and paper when thinking about literacy. The New London Group (Cope & Kalantzis, 2002) defines multimodal literacy as all the modes of literacy we engage in regularly. Multimodal literacy recognizes the technology we use, the media we read, and views text as more than words in a book. Multimodal literacy expands literacy to the modes we create and consume today—web pages, videos, podcasts, apps, and other forms of media and visual or auditory input. Many of us do not read a book or newspaper to get information. We rely on other modes of gaining information or enjoying entertainment. This matters for teaching reading because we can use various modes to teach students.

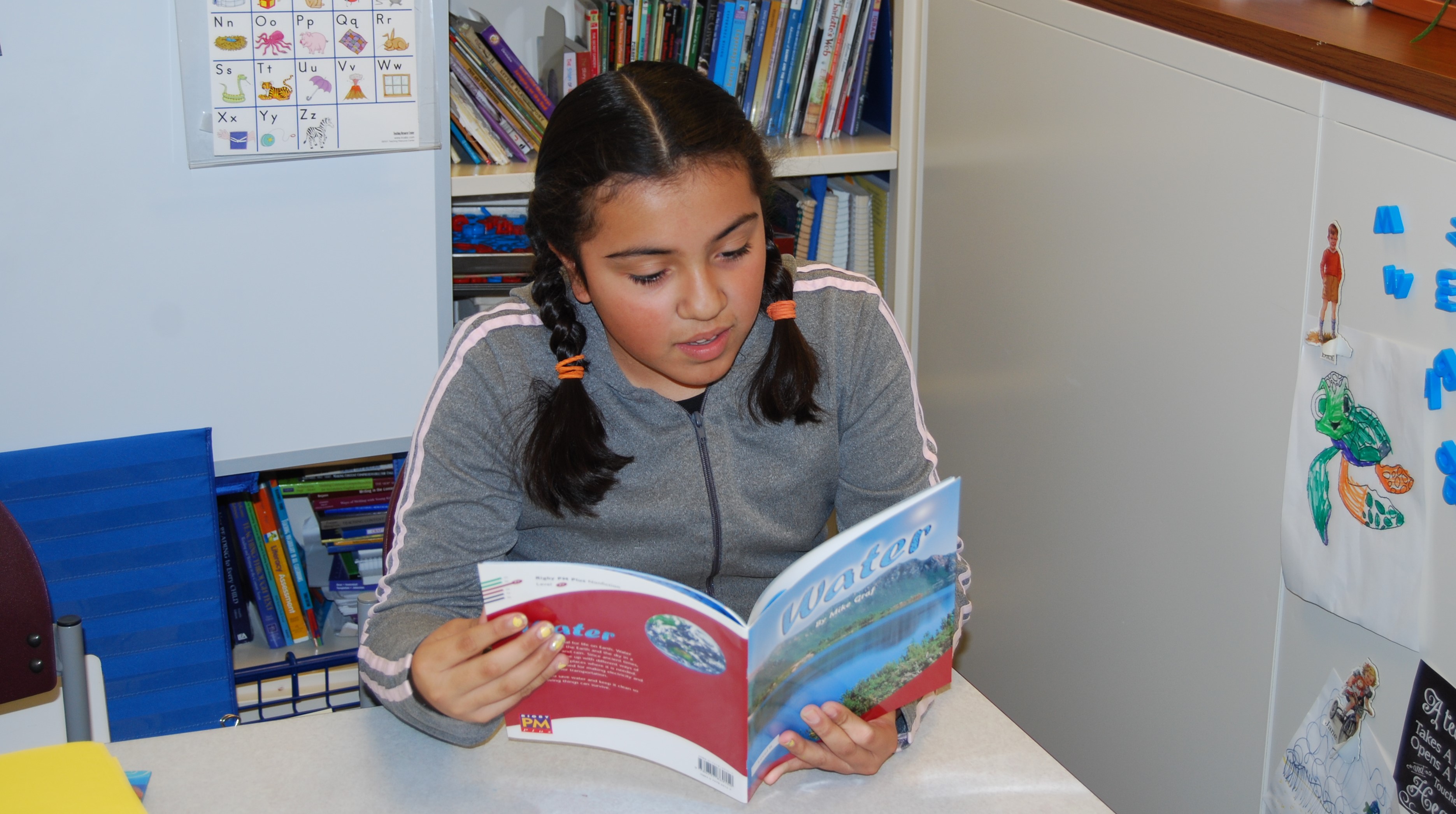

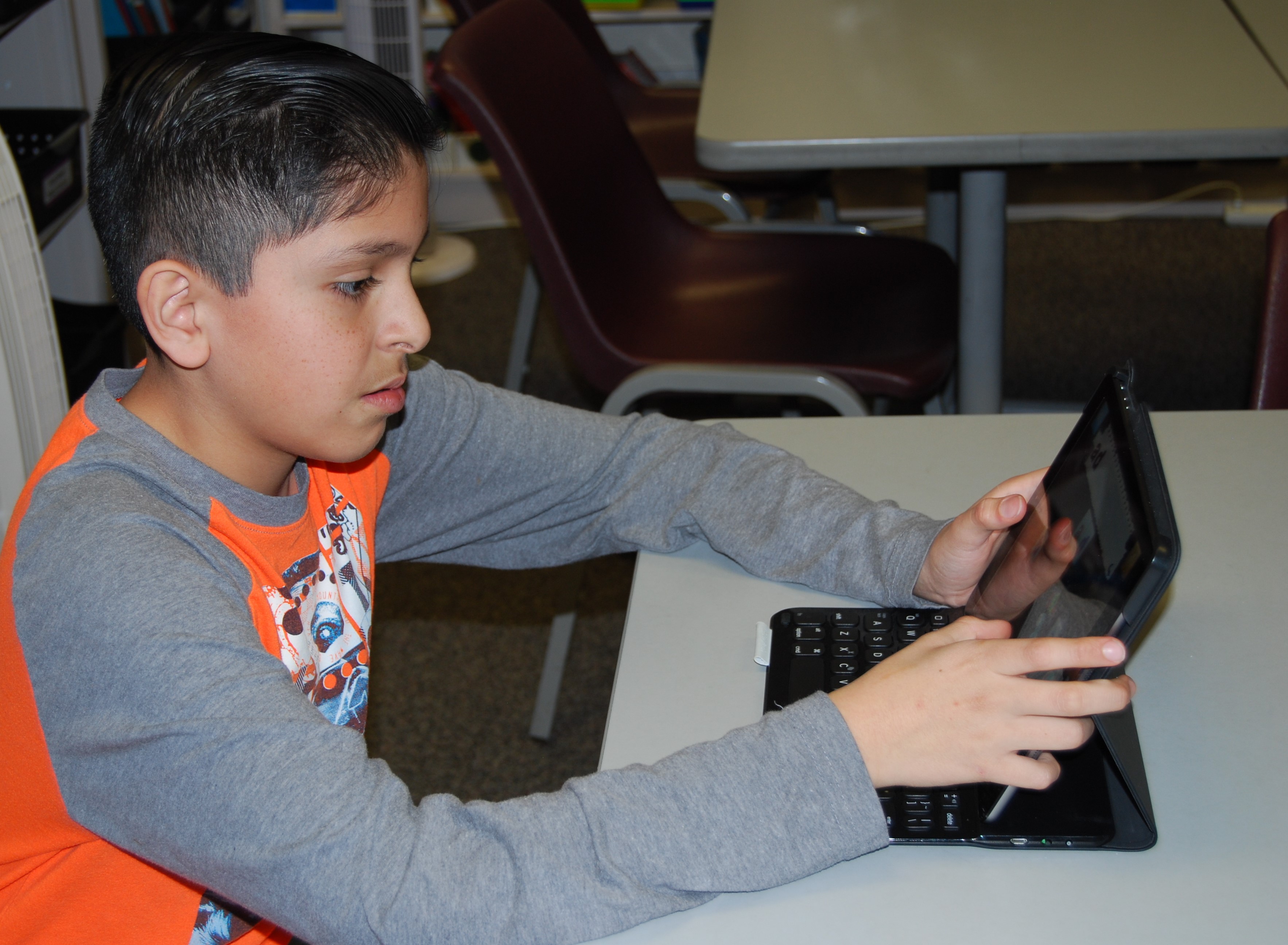

Students are already engaged in viewing and creating videos, playing video games, and reading websites with text, graphics, pictures, and videos. Multimodal literacy in tutoring allows us to bring all these modes into our teaching and allows students to make their own videos, blogs using text and visuals, and much more. Utilizing multiple modes of expression keeps students interested and connects their literacy learning to their lives outside of school.

What Are Developmental Levels?

Developmental Levels

Developmental reading levels refer to the predictable stages of reading young readers go through as they learn to read.

Developmental levels are very important to teaching literacy to young students. Working with elementary students is exciting when you see them making progress quickly. Yet due to the young age of students, it is helpful to look at how readers develop over time. While literacy is broad, developmental levels of reading highlight very specific reading behaviors that you can observe in your student. Most of us think about student reading abilities as they relate to grade level. We expect kindergarteners to learn their ABCs and be able to write the alphabet. We know that first grade is the year reading is taught to students, and that they should be able to read by the end of their first-grade year. Yet, research has shown us over time that grade levels or even student ages do not always fit students. Each student learns at their own pace.

Students do not always fit into grade-level expectations. Many kindergarteners can read books on their own, and some second graders may still be working on their alphabet sounds. Researchers and instructors (Clay, 1985; Fountas & Pinnell, 1996) have noted that while young students may learn at different rates, they still generally follow a certain path to learning how to read. This path is referred to as the developmental reading level. Please review Table 1.1.

As you read through the chart, note the descriptions and how they increase in complexity over time. Knowing where your student falls in the chart will help you not only to identify their developmental stage but also identify what types of activities you can plan to help them move to the next stage. The stages are described in ways that are observable. You can observe your student and begin to see where they are developmentally. The other assumption behind the developmental theory is that most students will progress through each stage in order. In addition to theories on how students learn in stages, developmental stages can help explain how students actually read.

Table 1.1 Developmental Reading Levels

|

|

Emergent Readers |

Early Readers |

Transitional Readers |

Self-Extending Readers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Description |

Use mostly information from pictures. May attend to and use some features of print. May notice how print is used. May know some words. May use the introduced language patterns of books. May respond to texts by linking meaning to their experiences. Beginning to make links between their oral language and print. |

Rely less on pictures and use more information from print. Have increasing control of early reading strategies. Know several frequently used words automatically. Read using more than one source of information. Read familiar texts with phrasing and fluency. Exhibit behaviors indicating strategies used as monitoring, searching, cross-checking, and self-correction. |

Have full control of early strategies. Use multiple sources of information while reading for meaning. Integrate the use of cues. Have a large core of frequently used words. Notice pictures, but rely very little on pictures to read the text. For the most part, read fluently with phrasing. Read longer, more complex texts. |

Use all courses of information flexibly. Solve problems in an independent way. Read with phrasing and fluency. Extend their understanding by reading a wide range of texts for different purposes. Read for meaning, solving problems in an independent way. Continue to learn from reading. Read much longer, more complex texts. Read a variety of genres. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Age and Grade Range |

Approximately ages 2 to 7 Preschool to early grade 1 |

Approximately ages 5 to 7 Kindergarten to grade 1 |

Approximately ages 5 to 7 Kindergarten to grade 2 |

Approximately ages 6 to 9 Grades 1 to 3 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Clay (1985); Fountas and Pinnell (1996) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What Is Psycholinguistic Theory?

Psycholinguistic theory applies to our view of tutoring due to its emphasis on the importance of meaning and understanding in reading (Goodman, 1967; Smith, 1971). At times, reading instruction can become disjointed and focus on smaller skills such as sounding out each word. A psycholinguistic view looks at how students use meaning to understand texts. This is compatible with our focus on student literacies and the developmental view of reading development. For example, you may be able to play tennis well when hitting balls coming from a machine. The machine is somewhat predictable; it can be set up to put the ball in a place that is comfortable for you. Being able to hit a tennis ball well when it is coming to you at a predictable speed and placement is one thing; a real tennis game in which your partner will not hit the ball directly toward you is very different. If students are taught one reading skill, such as sounding out words as they read, they will be only partially prepared to read actual texts. Many words, such as said, cannot be decoded. Therefore, you want to make sure you are teaching them many ways to read, just as a good tennis coach will work with you not only with the ball machine but also with an actual partner.

Psycholinguistic theory explains how readers use cueing systems as they read: (a) meaning/semantics, (b) grammar/syntax, and (c) visual/graphophonic (Goodman, 1967; Smith, 1971). Each cueing system is used by all readers. We all rely on sounding out words, using our knowledge of grammar and what we know about the meaning of the text we are reading. These three systems are automatic and occur very quickly and automatically in good readers, but for developing and struggling readers, they are not used efficiently or only one is used. Our goal is to recognize the value of the three cueing systems and teach them to students who are still learning how to read. For example, you may see some students who have been taught that reading is sounding out every word. While this is a very important part of reading and helps us to read unknown words, it is just one aspect of reading. There can be significant problems if this is the only reading strategy used, especially since words such as the, know, or saw cannot be sounded out successfully. Reading the sentence that follows will be extremely difficult for readers who only know how to decode words letter by letter:

I saw the cat.

For a reader who only knows how to read by decoding, the words saw and the will be problematic; the and saw are not words a reader can sound out letter by letter. If a reader can use their knowledge of grammar and meaning, they will be able to read the sentence. The grammatical structure of the sentence is familiar to English speakers. The order of the words is a common sentence pattern. The word cat is decodable, and the reader could use meaning to put all the words together. As is often the case with beginning level books, visual support with pictures can assist students with using meaning based on the picture. Psycholinguistic theory explains the importance of sounding out words, using grammar and meaning together in order to read. The terms used to delineate each cue are in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Reading Cueing Systems

|

Semantics (Meaning) |

Syntax (Grammar) |

Decoding (Visual) |

|

Relying on the meaning of the text. |

Relying on the grammatical structure of the text. |

Relying on the letter/sound decoding of the text and pictures. |

All three of these cueing systems work together as we read. Our goal is to develop each one in struggling readers so they can become independent readers.

Who Defines and Shapes Literacy in and out of School?

While we set up our tutoring program to embrace broad, multiple types and modes of literacy based on student knowledge, there are many stakeholders involved in literacy education. Students’ literacy experiences are shaped by the ideas of their families, their schools, and their communities. These areas are essential to understand because students’ learning is molded by the contexts of their lives. Since students’ literacy is influenced by family, school, and community, it is important for you to be aware of your student’s literacy.

Literacy Leaders: Families

Families are the first literacy teachers for their children. We discuss the significance of families in detail in Chapter 3, but for now it is important to understand that families influence students’ oral language, grammar usage, topic knowledge, and love or concerns about reading and writing. Knowing how families engage in literacy, how they read and talk with their children, and what types of experiences they have is key to providing relatable lessons to your student. Early on in your tutoring program, you will want to get to know your student’s family and what the families want for their child.

School Literacy

Schools are also a very strong influence on students’ literacy. Some schools rely on a psycholinguistic view of reading; others may use more skills-based phonics programs to teach reading. Knowing how your student has been taught to read is crucial. Some students may try to sound out each word because that is what they were taught, while others may guess at unknown words and not use the letter sounds. Knowing this can help you talk to students about other strategies they can use. Depending on your tutoring program, it can be difficult to learn about your student’s schooling, and you will have to be careful not to violate privacy laws. You may, however, ask your student how they learned to read and what was read in school. Most students can describe the types of books read in school and the activities they took part in.

Essential Elements of Literacy

As you can see, literacy is a broad and complex topic. As you tutor, the following essential elements will be important to remember as you learn about tutoring:

- All students possess literacy related to their background knowledge and experiences.

- Teaching literacy takes theory, student knowledge, and developmental levels into account.

- Literacy includes reading, writing, listening, and speaking but is multimodal and goes beyond books and pen and paper.

All of these elements are important to tutoring, and you will want to keep them in mind. Students need to be the center of your instruction as you plan for their unique developmental levels and knowledge.

Summary

Teaching students how to read and write using their existing literacies is an important job. The complex definitions and theories cited in this chapter will be used throughout the book. The lesson plans and detailed explanations of activities are all aligned with these ideas. You will see activities connected to real-world modes of learning and be asked to get to know your students and their families, and, of course, how to teach specific reading and writing strategies so your student can become highly literate. Please revisit the pre-reading questions to check and revise your initial answers.

How is literacy defined?

What types of literacies do you possess?

Clarify why you should know about your student’s literacy as you teach.