1 Kinesiology

Chapter 1

The Emergence of a New Field of Study

Student Objectives

- To appreciate the focus of inquiry in kinesiology

- To identify the various subfields or foundations in kinesiology

- To know the difference between cross- and interdisciplinary fields of study

- To understand the nature of a degree in kinesiology

- To identify a number of career options following a degree in kinesiology

- To become familiar with a case study on a cross-disciplinary approach to kinesiology

The Physical Activity Focus

Since ancient times, there has always been an interest in how and why humans engage in physical activity. Recently, there have been serious efforts to embody this interest within a coherent, scholarly field of study. The field of study we call today kinesiology is the result of these efforts. The term “kinesiology” derives from the Greek words kinesis (movement) and logos (the study of). The emphasis in kinesiology inquiry is on human movement, although animal movements are studied and used to help us better understand the human condition.

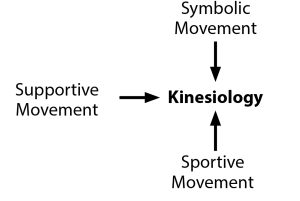

In the preface, a rationale for understanding human movement from several viewpoints was discussed. In Chapter 1, this rationale is further developed. A part of this rationale deals with the focus of inquiry in kinesiology. Should kinesiology as a field of study be restricted to a certain type of movement or physical activity? Should kinesiologists study sports? Is the study of dance within the focus of kinesiology? What about activities of daily living, such as tying one’s shoes, doing the dishes, or driving a car? Is physical exercise within the scope of kinesiology? The basic answer to these questions is essentially yes. As argued by Newell (1990), kinesiological inquiry can be used to study all types of physical activity, from spontaneous play, exercise, rehabilitation, to recreational and competitive sports. Charles (1994) suggested that there are three major types of movement that can be scrutinized by kinesiology researchers, as shown in Figure 1.1:

- Sportive movement—refers to skill-related physical activity

- Symbolic movement—physical activity that expresses thoughts and feelings through the symbolic medium of the body; the main emphasis is on physical expressiveness such as in dance, gestures, and speech

- Supportive movement—physical activity of a functional nature necessary to support a certain lifestyle and the major emphasis is health-related physical activity, such as the activities of daily living, rehabilitation from injury, disease prevention, and work

This distinction by no means implies that the categories of movement are mutually exclusive (Charles, 1994, p. 16). For example, a ballet dancer’s movements are clearly symbolic, but they are also sportive in the sense that they reflect the skill of the dancer. In addition, ballet movements also may be supportive if the dancer considers their production as contributing to the dancer’s health. Thus, any observed movement could fit into one or more categories.

Knowledge gained from the study of one type of movement may also apply to our understanding of the other types. For example, many supportive movements have to be learned first before they can be used. That is, whether one engages in supportive movement may depend on how well the movement can be executed. For example, a person with an amputation, who could functionally benefit from the use of an artificial hand, often rejects using it because of the lack of sufficient motor control—that is, the ability to control movements. As pointed out by McKensie (1970) some time ago, “Learning to use an arm prosthesis never comes instinctively, and its effective use is an acquired skill, so much so that no worthwhile return in the way of function is apparent to the user, and rejection may result.” This is just one example of how an understanding of one type of movement (sportive or skillful) can facilitate the understanding of another (supportive).

In addition to the three major types of movements studied by kinesiologists, there also are a variety of settings where they may be examined. We can expect the qualities of human movement to be at least partly dependent on the situation. For example, sportive, symbolic, and supportive movements all can be studied in the laboratory where the researcher can better control the environmental conditions. Much kinesiology research has been investigated in this setting. However, further insight into physical activity can be gained by studying human movement outside of the laboratory in more real-life conditions, such as in the workplace, the clinic, the gymnasium, the dance studio, the swimming pool, a city park, or on a mountain. There is much to learn about human physical activity in natural settings, where the difficulties of controlling environmental influences can be offset somewhat by the richness of the information gathered. In addition, some physiological and psychological contributions to movement will vary from one physical activity setting to another, while others will not. How we experience and ascribe meaning to physical activity may also likely depend on the physical activity setting.

Differences and similarities in human physical activity can be examined across cultures, racial and ethnic groups, socioeconomic status; between the sexes; and across different developmental ages. While the focus of kinesiology is on human physical activity, this does not imply a restriction to only human inquiry. Often, insight into human physical activity can be gained by studying other animals before applying this knowledge to humans. In addition, a growing amount of physical activity research uses computer technology, where the researcher relies on computer models and simulations of human and animal movement. Here, human or animal movement is investigated through the use of a set of derived equations! The researcher derives such equations to mimic a theoretical model of movement or factors affecting movement and tests the model using computer simulations before applying the model to actual human behavior. Thus, some scientific inquiries of physical activity are not performed in the experimental laboratory or in the natural environment but on the computer! In summary, restricting our inquiry to a certain type of movement, setting, type of individual, or model will only serve to limit our understanding of the various dimensions of human physical activity.

Adapted from Charles (1994).

Subfields in Kinesiology

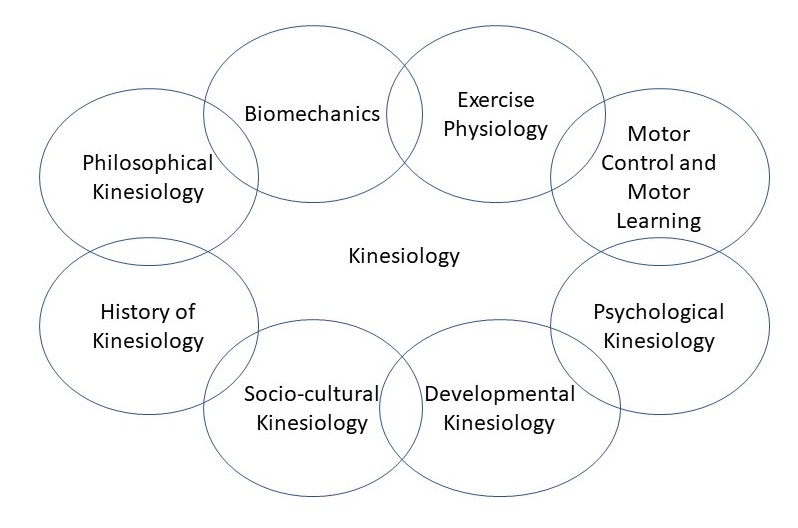

Figure 1.2 illustrates a conceptualization of kinesiology made up of various subdisciplines or subfields. In this conceptualization, the major subfields of kinesiology are the history of kinesiology, biomechanics, exercise physiology, motor control and motor learning, developmental kinesiology, psychological kinesiology, sociocultural kinesiology, and philosophical kinesiology. The circles representing the subfields are purposely placed close to one another and all connect to the field of kinesiology. As a result, the content of each subfield can be thought to be connected both to the field of kinesiology and to the other subfields. In this way, the field of kinesiology can be thought of as an “integrative” field of study.

In my view, no subfield is more important than another because without information from a subfield, a more complete understanding of how and why humans move, work, and perform in the environment is not possible. As we will see in subsequent chapters, each subfield focuses on a certain aspect of human physical activity. The subfields identified in Figure 1.2 have been well researched for a number of years and contain a number of facts, models, theories, and phenomena.

The chapter entitled The History of Kinesiology documents, in more or less chronological order, the relative importance of physical activity to society from ancient to modern times. This chapter also identifies important people in history who have either studied physical activity or have affected the promotion of physical activity. Finally, the history of kinesiology as a developing field of study is examined.

The Anatomical and Physiological Systems chapter is an overview of some of the major anatomical structures and important physiological systems of the human body. This chapter has been included to give the reader some useful background before going into the various subfields within kinesiology. The Exercise Physiology Foundations chapter is the study of how the structures and the various physiological systems in the body adapt acutely and chronically to the stress of exercise. The Biomechanical Foundations chapter provides a detailed description of the muscular forces produced by the human body and the mechanics of human motion. How movements are controlled, coordinated, and learned is investigated within the Motor Control and Motor Learning chapter. The Psychological Kinesiology chapter explores the various cognitive, emotional, and social factors that affect both how and why we move and perform in a number of physical activity environments. Changes in both the structure and function of the human body over the life span are investigated within the Developmental Kinesiology chapter. Some may argue that development is not a separate subfield, but rather a dimension of the other subfields. I understand this argument. However, there is sufficient accumulated knowledge of the human development and aging process to consider development as a unique subfield. The Sociocultural Kinesiology chapter examines the many social and cultural factors that influence human physical activity. Finally, there is the Philosophical Kinesiology chapter that examines a variety of philosophical perspectives and issues in kinesiology.

Some time ago, Jerry Barham (1963, 1966) conceptualized the various subfields in a unique way by using different adjectives in front of the noun kinesiology. For example, biomechanics was called mechanical kinesiology, and exercise physiology was called physiological kinesiology. Using Barham’s conceptualization, I have characterized some of the subfields in this way, as shown in Figure 1.2.

One could argue that specific names for each subfield should be dropped altogether and replaced by a thematic area within kinesiology. For example, in 1990, Newell suggested the following five thematic areas that attempt to cover the entire scope of kinesiological inquiry: coordination, control, and skill; growth, development, and form; energy, work, and efficiency; involvement, achievement, and enculturation; aesthetics, meanings, and values.

There is merit in Newell’s proposal because a thematic approach attempts to link the various subfields and helps promote cross-disciplinary knowledge (see the following and Chapter 10). The adjective descriptions of the subfields also bring a sense of unity to kinesiology inquiry. The traditional names of the subfields are probably adequate because they accurately represent the content within kinesiology, and they are familiar to most people in the field. However, both the Barham and Newell proposals for describing the developing field of kinesiology have merit and are worthy of further consideration.

Levels of Analysis

The antecedents (causes) and the consequences (outcomes) of human movement can be examined at different levels of analysis. A level of analysis can be thought of as representing the size of the unit under investigation. In describing the human engaged in physical activity, there are several levels of analysis: molecular, cellular, systems, behavioral, psychological, and sociocultural. Each subfield in kinesiology focuses on a certain level(s) of analysis to evaluate the antecedents and consequences of physical activity. Below the molecular level are the atomic and subatomic levels. But these levels are not widely examined in kinesiology, compared to the field of nuclear physics, for example.

The unit of study at the molecular level of analysis is extremely small. Observing and measuring events at this level of analysis requires sophisticated tools such as the electron microscope. For example, the molecular level of analysis has been used by exercise physiologists to examine how muscle contraction occurs. Magnetic resonance imaging measures the number of certain atoms at different locations in the body. This technique has been used by motor control researchers to measure brain activity during movement. It also has been used by biomechanics and exercise physiology researchers to study a variety of anatomical and physiological functions.

At the cellular level of analysis, cellular events occurring in the nerve, bone, muscle, and other tissues are examined. The cellular level of analysis is used primarily by the biomechanics, exercise physiology, and motor learning and control subfields.

At the systems level of analysis, activity within the various physiological systems is evaluated, such as the nervous, skeletal, muscular, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems, to name a few. Once again, the biomechanics, exercise physiology, and motor learning and control subfields extensively examine this level of analysis. There are also some researchers in sport and exercise psychology who measure events occurring in certain physiological systems.

At the behavioral level of analysis, movements that are readily observable by the naked eye are measured or evaluated. At the behavioral level of analysis, we can examine the causes or antecedents of movement using the principles of kinetics, a major area of biomechanics that studies the forces produced by or exerted on the body. Kinetic measures such as force can be examined through the use of devices called strain gauges, force transducers, and force platforms. Kinematics, another major area within biomechanics, examines the various biomechanical descriptions of movement such as displacement, velocity, and acceleration of the limbs or body. Kinetic and kinematic measures can also be used at the systems and cellular levels of analysis. An example of a kinematic measurement tool is motion analysis technology, such as videotape analysis. Certain types of markers are strategically placed on the body, the motion is videotaped, and the changes in markers’ positions during the movement are digitized and entered into a computer for analysis purposes. There are also other sophisticated technologies today that allow for kinematic measurement (see Magill, 2011).

Some years ago, Higgins (1977) proposed that the events at the behavioral level also could be examined using kinesic and subjective-description measurement. Kinesic measurement is a qualitative method to evaluate nonverbal communicative behavior of an individual or between individuals. It can be used to measure nonverbal communication of a performer, teacher, or coach, for example. Subjective description is another way to qualitatively evaluate movement based on the opinion of the evaluator. A golf instructor evaluating a student’s swing or an audience watching a dance performance are examples of subjective descriptions of movement. The outcome of the movement, involving the consequence, efficiency, and effectiveness of the goal accomplishment of the movement, can also be evaluated (Higgins, 1977). Did the basketball go in the basket, did the dart hit the bull’s-eye, is the amputee improving in the use of a new prosthesis are examples of questions that can be raised about movement outcome. How efficiently a movement is produced can also be examined. Thus, at the behavioral level of analysis, the causes, description, and outcome of movement can be evaluated. The behavioral level of analysis has been used by all the subfields in kinesiology.

At the psychological level of analysis, cognitive and emotional events of the human are evaluated. Measurement of cognitive and emotional events may take the form of validated questionnaires or interviews. These types of measurements assess the mental events associated with participating in physical activity, such as the motivation of the individual. The psychological level of analysis is used primarily in the sport and exercise psychology subfield, but some of the other subfields also take measures at this level of analysis (Duda, 1998, 471–483).

The sociocultural level of analysis examines the largest unit of study in kinesiology: the behavior of groups of people or societies. One example of a question addressed at this level of analysis is, What sociocultural factors influence the participation of an individual or a large group of individuals in physical activity? Does the racial or ethnic background of a group of people affect their participation in exercise? Does the socioeconomic status of a group of people have an effect on whether they choose to live a physically active lifestyle or not?

Other than the size of the unit, another distinguishing characteristic of the various levels of analysis are time-scale differences. Time scales can be thought of as the elapsed time between significant events occurring at a given level of analysis. The fastest time scale occurs at the molecular level of analysis (not including the atomic or subatomic levels) and the slowest time scale occurs at the sociocultural level of analysis. In other words, important changes in events occur at a much faster rate at the molecular level, sometimes on the order of nanoseconds (i.e., one billionth of a second), compared to the sociocultural level, where significant events may be separated by years, decades, or even centuries! One of the great challenges for kinesiologists is determining the proper time scale between important events at any given level of analysis and making measurements that encompass that time scale. For example, the time scale for a given muscle contraction, say for flexing the elbow, might be no longer than a second or two. However, what is the time scale for understanding why a person chooses not to engage in a physically active lifestyle? The relevant time scale is certainly not as short as two seconds! But what is the relevant time scale in this case? Answering the question depends on the definition of what is meant by “a significant event” at a given level of analysis. The events that occur at a particular level are numerous. The researcher must determine which are the relevant and irrelevant events before a time scale can be determined. Determining what are relevant and irrelevant events at any given level of analysis is a difficult but nonetheless important challenge facing research in kinesiology, as well as in other fields of study.

All the levels of analysis operate as an individual is engaged in physical activity. When we perform a golf swing, molecular events are occurring at unbelievable rates, contributing to both the physical and cognitive aspects of the performance. But superimposed on molecular events are all the other levels of analysis that contribute in certain ways to the swing. As a result of the many important processes occurring at different time scales of the various levels of analysis, the golf swing occurs! It must be the case that there is some relationship between what is happening at the molecular level and the other levels. Indeed, yet another major challenge to researchers in kinesiology (as well as other fields of study) is how the events at any one level of analysis relate to events at the other levels.

The last point I want to make in this section is that because all behavioral movements are influenced by all the levels of analysis, no one level of analysis is more important than another. Ignoring one or more levels of analysis results in an incomplete description of the movement. If we ignore the molecular, cellular, or systems level of analysis, the physiological description of the movement is lost. If the psychological level is ignored, we fail to appreciate the motivation for performing the movement, for example. The sociocultural level of analysis provides the overall context of the movement and probably helps define the meaning of the movement to the individual.

While all levels of analysis are required to fully describe a movement, a particular level of analysis might be more appropriate for certain situations. For example, the three types of movement (i.e., sportive, symbolic, and supportive) can be investigated from several levels of analysis. In some cases, a particular level of analysis may be necessary to measure a given type of movement or movement situation. For example, if a golfer is slicing the ball and wishes to improve the swing, the instructor may wish to analyze the behavioral level of analysis through videotaping. In this way, the student may be able to actually see what is wrong with the swing. In this situation, the student’s heart rate, one measure of the cardiovascular system, is probably irrelevant in terms of providing helpful information that could be used to correct the student’s slice. This example appears rather straightforward; however, determining the most useful level of analysis for understanding a certain movement or movement situation is another important challenge faced by kinesiologists. The reasoning is that movements, and their antecedents and consequences, are complex, and complex phenomena are difficult to describe and understand.

Cross- and Interdisciplinary Fields of Study

Each foundation of kinesiology has been investigated by scholars both within and outside of kinesiology. For example, medical researchers have contributed to the development of the exercise physiology foundation and researchers in the field of psychology have helped in laying some of the groundwork in the motor learning/control and psychological foundations. To some extent, each of the foundations could be part of other disciplines, such as physiology or psychology. However, the major focus of kinesiology is human movement and physical activity from a number of perspectives. As such, it is different from the major focus of other academic disciplines.

If research in each subfield or foundation in kinesiology were to continue in an isolated fashion without any integration from the other subfields, then kinesiology would become an interdisciplinary field of study (see Henry, 1978; Lawson & Morford, 1979, for excellent discussions). This type of academic discipline develops subfields that typically become highly specialized. Researchers in each subfield develop unique research skills and techniques and speak a “different language” in describing the content within their specialized area. In this scenario, each subfield becomes so specialized that it could be encompassed within a traditional or parent discipline (e.g., biomechanics into physics, exercise physiology into biology, sport, and exercise psychology into psychology). In some present-day departments of kinesiology, it is common for researchers in exercise physiology, for example, to have little interaction with their colleagues in sport and exercise psychology, in spite of the fact that there are many areas of potential overlap and issues of common interest. I suspect similar interdisciplinary trends are evident in many other scientific fields of study.

Cross-disciplinary means that the focus of the field of study is the communication and interaction among the subfields and not just the isolated advancement of each subfield. Many academic fields of study, such as psychology, physics, and chemistry, started out being cross-disciplinary, but as time went on, they tended to become more interdisciplinary in nature because of specialization and fragmentation. Suffice it to say, interdisciplinary research within each subfield of kinesiology is important, but a more comprehensive understanding of how and why we engage in physical activity is likely to be better achieved through cross-disciplinary research. With cross-disciplinary research, thematic problems within the field of kinesiology can be explored using expertise and knowledge from more than one subfield. For example, the question “How does one improve cardiovascular fitness?” can be addressed from several subfield perspectives. From an exercise physiology point of view, specific physiological training techniques can be evaluated. From a sport and exercise psychology perspective, the proper motivational orientation of the individual can be assessed. From a developmental viewpoint, the age of an individual can affect the type of training technique used and may have an influence on the individual’s motivation. Whether the individual initiates and adheres to a cardiovascular fitness program may depend on his or her socioeconomic background and information emphasized from a sociocultural point of view. Whether kinesiology as a field of study develops into an interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary field of study is an open question.

However, the view presented in this textbook is that a cross-disciplinary approach to kinesiology can provide a unique perspective on the many issues related to participation in physical activity. To give the reader, and beginning kinesiology students, a better appreciation of this approach, a case study will be described at the end of this chapter that will be examined repeatably throughout the textbook. After the reader finishes reading a given chapter focusing on a particular subfield in kinesiology, the reader will then be given an opportunity to use the knowledge gained from that subfield to address the case study. By the end of the book, the reader will have addressed the case study from a wide variety of perspectives using the knowledge gained from each subfield. As a result, it is hoped that the reader and beginning kinesiology study have a much better appreciation of the cross-disciplinary approach.

Types of Knowledge in Kinesiology

As with other fields of study, the content of kinesiology consists of declarative and procedural knowledge (Ryle, 1949). One type of declarative knowledge is the theoretical and empirical information generated within a field of study as a result of scientific research. After decades of research in the various subfields, kinesiology as a field of study contains considerable declarative knowledge about humans engaged in physical activity. The views of Franklin Henry, expressed in two important papers (1964, 1978), had much to do with the emphasis on declarative knowledge in the kinesiology curriculum today in most universities. Actually, as pointed out by Tulving (1972), declarative knowledge can be divided into semantic and episodic. Semantic, declarative knowledge, is that theoretical and empirical information generated by scientific research referred to here. However, episodic, declarative knowledge, is that information gained through personal experiences, a type of knowledge not emphasized in this book.

Another type of declarative knowledge is that generated by the practitioner, such as the physical education teacher, sports coach, and exercise trainer (Newell, 1990). We have all probably met practitioners in the field, such as physical education teachers or coaches who have declarative knowledge of their profession of a practical nature. The declarative knowledge they possess is about the real-world setting of their profession. For example, it is one thing to know about the biomechanics of a soccer kick, but it is quite another to be able to teach soccer to elementary school children. Any beginning student physical education teacher will confirm this point! There are many “tricks of the trade” in any profession, some gained with theoretical knowledge but much usually gained from years of practical experience on the job. One reason for bringing up this distinction between types of knowledge is to emphasize that this book is primarily about declarative knowledge of the theoretical and empirical types within kinesiology. However, real-life examples of how theoretical information can be used in practical settings will be discussed throughout the book.

Procedural knowledge entails knowing how to do something. In the case of kinesiology, procedural knowledge may pertain to the ability to execute a movement or an action. Having procedural knowledge of a golf swing means being able to actually execute the golf swing. In many physical education degrees and some kinesiology degrees, it is required for students to demonstrate their ability to perform certain skills or exercises or be required to take physical activity classes. The emphasis on procedural knowledge is common in most dance degrees. Procedural knowledge also can be demonstrated in laboratories associated with lecture classes in kinesiology classes. The ability to perform certain measurement techniques at a given level of analysis indicates some mastery of procedural knowledge. Student demonstrations of a movement, skill, or exercise in a lecture or laboratory class are other examples of procedural knowledge. It is my view that declarative and procedural knowledge about humans engaged in physical activity should be part of the kinesiology curriculum.

Three Aspects of Kinesiology Programs

According to Newell (1990), a kinesiology program at the university level can consist of three emphases: disciplinary, professional, and performance. The disciplinary emphasis relates primarily to the declarative knowledge within kinesiology—that is, the theoretical information within the various subfields. In most universities, a disciplinary emphasis is required in all fields of study. The professional emphasis focuses on preparing the student for a specific career or profession. In physical education departments and some kinesiology departments, students may major in physical education that will prepare them to become a physical education teacher in elementary or secondary school, a sports coach, or sports administrator, for example. In other kinesiology departments, the professional emphasis is not a part of the curriculum. The performance emphasis relates primarily to certain aspects of procedural knowledge within kinesiology—for example, the demonstration of skill for competitive or aesthetic purpose. According to Newell (1990), this emphasis greatly decreased over the last few decades in most physical education and kinesiology programs. In fact, the field of dance, which used to be an inherent part of physical education before kinesiology evolved, moved out of physical education and formed its own degree program in many universities. The performance emphasis is typically less emphasized in most kinesiology curricula across North America.

In my view, whether the three program emphases are part of a given degree or not, people in a given emphasis can benefit from the knowledge generated in the other two. For instance, the theoretical knowledge generated by researchers in the disciplinary emphasis may be useful to both the physical activity practitioner and the performer. Examples of physical activity practitioners are physical education teachers, coaches, exercise leaders, physical therapists, and other health professionals. Physical activity performers may include dancers and other athletes. While debated (Best, 1978; Newell, 1990), it is possible for the three types of emphases (theoretical, practitioner, and performance) to inform each other. Practitioners such as physical education teachers can apply principles of biomechanics, exercise physiology, and other subfields to their teaching of exercise habits and motor skill development. Basic knowledge of kinesiology can help physical therapists develop preventive injury or rehabilitation programs for their clients.

It is also possible, I believe, for the researcher to gain insight into theoretical physical activity problems by studying or interacting with professionals, clinicians, or performers. “Real-world” problems faced by these professionals, clinicians, and performers offer the researcher a steady reminder of the complexity of behaviors outside the laboratory. The kinesiology researcher can potentially gain great insight into a physical activity problem by conducting research outside of the laboratory. Field research is a common strategy used by researchers in the psychological and sociocultural areas but is also practiced by some researchers in other subfields. Performers also can benefit from the other two areas. A dancer who interacts with a physical activity researcher may discover a better method to improve his or her leg strength. If the dancer becomes injured, knowledge gained by communication with a physical therapist may improve rehabilitation and help in preventing future injury.

The Degree in Kinesiology

Regardless of the desired career, it is important for kinesiology students to receive a strong liberal arts education. A liberal arts education exposes the student to a wide variety of areas of study outside of the student’s specific major. A liberal arts education is designed to provide the student with a greater perspective of the world and an appreciation of the importance of different fields of study, regardless of one’s specific interest (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2020). In addition, many liberal arts courses can provide important background for understanding the content in the various subfields of kinesiology. For example, general psychology provides an excellent foundation for the study of sports and exercise psychology. Chemistry and biology are important prerequisites for exercise physiology. Physics is important for a better understanding of biomechanics. In many kinesiology degrees, quantitative reasoning, usually in basic mathematics, is often required as a prerequisite because many kinesiology classes require an understanding of statistics and other quantitative skills. In my opinion, it is important that students take the necessary prerequisite coursework that adequately prepares them for kinesiology.

In most kinesiology degrees, classes in the major subfields of kinesiology, like the subfields described in this chapter, are common. To provide a basic understanding of the field of kinesiology and to provide students with various career options following a degree in kinesiology, an Introduction to Kinesiology class is often offered. Following the introduction class, students then take so-called core classes that all kinesiology students must take. The kinesiology core classes are designed to introduce students to the various subfields within kinesiology. It is also often the case that many of the core classes in kinesiology are accompanied by laboratory sections that allow students to apply their knowledge to various physical activity issues. Following these core classes, a number of elective classes in kinesiology are offered to further prepare students for specific careers in kinesiology or to expand on their interests. Some examples of elective classes might be athletic training, strength and conditioning, aging, nutrition and performance, management of exercise and wellness programs, and prevention and treatment of performance and sports injuries. In addition, internship classes might be offered that allow the student to apply their knowledge of kinesiology in the community, like in schools or clinics. Independent study opportunities might be offered that allow the student to work more closely with a faculty member on research projects. Finally, some degrees in kinesiology require the student to take physical activity classes, such as swimming, weight lifting, yoga, or tennis, for example. These types of classes allow the student to enhance their procedural knowledge of kinesiology, as discussed earlier in this chapter.

Career Opportunities

Many students contemplating kinesiology as an undergraduate major ask the following question: “What can I do with a degree in kinesiology?” The highlight box provides some information to help answer that question. Listed here are a number of areas of study and career opportunities for students who start with an undergraduate degree in kinesiology or an equivalent degree in exercise, sports, or human movement science, as some departments have opted to call themselves. It should be emphasized that an undergraduate degree in kinesiology is usually not sufficient, as is the case in most other fields of study, to land a high-salaried job. In many cases, advanced degrees and practical experiences leading to certification in a specialty area are required.

First of all, countless studies have concluded that a college degree in any major is an asset in many ways in later life (e.g., Hout, 2012). Most liberal arts degrees (e.g., psychology, biology, and mathematics) are not designed to lead to a specific employment opportunity but rather to provide a well-rounded education and to develop the basic knowledge and skills inherent in almost any occupation. One of the requirements of a liberal arts degree is a concentration of work in one specific area known as a major. In most cases, students naturally select an area of interest in which to major in, and, of course, it makes sense that this might lead to some related employment situation in the future. Thus the question, “What can I do with a degree in kinesiology?”

In an attempt to answer this question, the following occupations and fields related to kinesiology were compiled:

|

Adapted Physical Education |

Nutrition Science |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aerospace Medicine |

Occupational Therapy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Allied Health |

Ophthalmology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anatomical Science |

Optometry |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anatomy |

Orthopedic Assistant |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Anesthesiology Education |

Orthopedic Medicine |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Applied Physiology |

Osteopathic Therapy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Aquatics Director |

Osteopathy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Athletic Clubs |

Outdoor Education |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Athletic Director |

Paramedic |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Athletic Training |

Park and Recreation Resources |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Athletic or Sports Administration |

Pharmacology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Biobehavioral Science |

Physical Ed/Special Population |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Biodynamics |

Physical Education |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Biomedical Engineering |

Physical Therapist |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Biomedical Science |

Physical Therapy/Aid |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Buying and Selling Equipment |

Physical Therapy Assistant |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Camp Director |

Physician’s Assistant |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cardiac Rehabilitation |

Physiology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cardiopulmonary Technology |

Podiatry |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cardiorespiratory Science |

Preschool Program |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Cell Biology |

Preventive Medicine |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chiropody |

Private Sports/Rec Clubs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chiropractic |

Promotional Manager—Sports Equipment |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Clinical Biology |

Psychiatric Medicine |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Clinical Medicine |

Psychomotor Therapy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Coaching |

Public Health |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Corporate Fitness/Wellness |

Radiation Technology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Administration |

Radiation Therapy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health-Care Management |

Radiological Technology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Club/Management |

Recreation |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Education |

Recreation Administration |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Fitness Management |

Recreation Leadership |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Promotion |

Recreational Therapy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Records |

Recreation and Leisure |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Science Administration |

Recreation and Parks |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Services |

Rehabilitation Specialist |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health Spa Management |

Research Assistant |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Health and Wellness |

Resort Programs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Home Economics/Nutrition |

Sport Information |