3 Reading 2: Selection from "Introduction to Psychology"

Reading 2

History of Psychology

Psychology is a relatively young science with its experimental roots in the 19th century, compared, for example, to human physiology, which dates much earlier. As mentioned, anyone interested in exploring issues related to the mind generally did so in a philosophical context prior to the 19th century. Two men, working in the 19th century, are generally credited as being the founders of psychology as a science and academic discipline that was distinct from philosophy. Their names were Wilhelm Wundt and William James. This section will provide an overview of the shifts in paradigms that have influenced psychology from Wundt and James through today.

Wundt and Structuralism

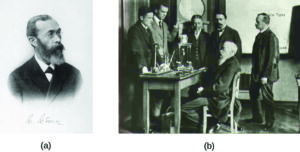

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) was a German scientist who was the first person to be referred to as a psychologist. His famous book entitled Principles of Physiological Psychology was published in 1873. Wundt viewed psychology as a scientific study of conscious experience, and he believed that the goal of psychology was to identify components of consciousness and how those components combined to result in our conscious experience. Wundt used introspection (he called it “internal perception”), a process by which someone examines their own conscious experience as objectively as possible, making the human mind like any other aspect of nature that a scientist observed. Wundt’s version of introspection used only very specific experimental conditions in which an external stimulus was designed to produce a scientifically observable (repeatable) experience of the mind (Danziger, 1980). The first stringent requirement was the use of “trained” or practiced observers, who could immediately observe and report a reaction. The second requirement was the use of repeatable stimuli that always produced the same experience in the subject and allowed the subject to expect and thus be fully attentive to the inner reaction. These experimental requirements were put in place to eliminate “interpretation” in the reporting of internal experiences and to counter the argument that there is no way to know that an individual is observing their mind or consciousness accurately, since it cannot be seen by any other person. This attempt to understand the structure or characteristics of the mind was known as structuralism. Wundt established his psychology laboratory at the University at Leipzig in 1879 (Figure 1.2.1). In this laboratory, Wundt and his students conducted experiments on, for example, reaction times. A subject, sometimes in a room isolated from the scientist, would receive a stimulus such as a light, image, or sound. The subject’s reaction to the stimulus would be to push a button, and an apparatus would record the time to reaction. Wundt could measure reaction time to one-thousandth of a second (Nicolas & Ferrand, 1999).

However, despite his efforts to train individuals in the process of introspection, this process remained highly subjective, and there was very little agreement between individuals. As a result, structuralism fell out of favor with the passing of Wundt’s student, Edward Titchener, in 1927 (Gordon, 1995).

James and Functionalism

William James (1842–1910) was the first American psychologist who espoused a different perspective on how psychology should operate (Figure 1.2.2). James was introduced to Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection and accepted it as an explanation of an organism’s characteristics. Key to that theory is the idea that natural selection leads to organisms that are adapted to their environment, including their behavior. Adaptation means that a trait of an organism has a function for the survival and reproduction of the individual, because it has been naturally selected. As James saw it, psychology’s purpose was to study the function of behavior in the world, and as such, his perspective was known as functionalism. Functionalism focused on how mental activities helped an organism fit into its environment. Functionalism has a second, more subtle meaning in that functionalists were more interested in the operation of the whole mind rather than of its individual parts, which were the focus of structuralism. Like Wundt, James believed that introspection could serve as one means by which someone might study mental activities, but James also relied on more objective measures, including the use of various recording devices, and examinations of concrete products of mental activities and of anatomy and physiology (Gordon, 1995).

Freud and Psychoanalytic Theory

Perhaps one of the most influential and well-known figures in psychology’s history was Sigmund Freud (Figure 1.2.3). Freud (1856–1939) was an Austrian neurologist who was fascinated by patients suffering from “hysteria” and neurosis. Hysteria was an ancient diagnosis for disorders, primarily of women with a wide variety of symptoms, including physical symptoms and emotional disturbances, none of which had an apparent physical cause. Freud theorized that many of his patients’ problems arose from the unconscious mind. In Freud’s view, the unconscious mind was a repository of feelings and urges of which we have no awareness. Gaining access to the unconscious, then, was crucial to the successful resolution of the patient’s problems. According to Freud, the unconscious mind could be accessed through dream analysis, by examinations of the first words that came to people’s minds, and through seemingly innocent slips of the tongue. Psychoanalytic theory focuses on the role of a person’s unconscious, as well as early childhood experiences, and this particular perspective dominated clinical psychology for several decades (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

Freud’s ideas were influential, and you will learn more about them when you study lifespan development, personality, and therapy. For instance, many therapists believe strongly in the unconscious and the impact of early childhood experiences on the rest of a person’s life. The method of psychoanalysis, which involves the patient talking about their experiences and selves, while not invented by Freud, was certainly popularized by him and is still used today. Many of Freud’s other ideas, however, are controversial. Drew Westen (1998) argues that many of the criticisms of Freud’s ideas are misplaced, in that they attack his older ideas without taking into account later writings. Westen also argues that critics fail to consider the success of the broad ideas that Freud introduced or developed, such as the importance of childhood experiences in adult motivations, the role of unconscious versus conscious motivations in driving our behavior, the fact that motivations can cause conflicts that affect behavior, the effects of mental representations of ourselves and others in guiding our interactions, and the development of personality over time. Westen identifies subsequent research support for all of these ideas.

More modern iterations of Freud’s clinical approach have been empirically demonstrated to be effective (Knekt et al., 2008; Shedler, 2010). Some current practices in psychotherapy involve examining unconscious aspects of the self and relationships, often through the relationship between the therapist and the client. Freud’s historical significance and contributions to clinical practice merit his inclusion in a discussion of the historical movements within psychology.

Wertheimer, Koffka, Köhler, and Gestalt Psychology

Max Wertheimer (1880–1943), Kurt Koffka (1886–1941), and Wolfgang Köhler (1887–1967) were three German psychologists who immigrated to the United States in the early 20th century to escape Nazi Germany. These men are credited with introducing psychologists in the United States to various Gestalt principles. The word Gestalt roughly translates to “whole;” a major emphasis of Gestalt psychology deals with the fact that although a sensory experience can be broken down into individual parts, how those parts relate to each other as a whole is often what the individual responds to in perception. For example, a song may be made up of individual notes played by different instruments, but the real nature of the song is perceived in the combinations of these notes as they form the melody, rhythm, and harmony. In many ways, this particular perspective would have directly contradicted Wundt’s ideas of structuralism (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

Unfortunately, in moving to the United States, these men were forced to abandon much of their work and were unable to continue to conduct research on a large scale. These factors along with the rise of behaviorism (described next) in the United States prevented principles of Gestalt psychology from being as influential in the United States as they had been in their native Germany (Thorne & Henley, 2005). Despite these issues, several Gestalt principles are still very influential today. Considering the human individual as a whole rather than as a sum of individually measured parts became an important foundation in humanistic theory late in the century. The ideas of Gestalt have continued to influence research on sensation and perception.

Structuralism, Freud, and the Gestalt psychologists were all concerned in one way or another with describing and understanding inner experience. But other researchers had concerns that inner experience could be a legitimate subject of scientific inquiry and chose instead to exclusively study behavior, the objectively observable outcome of mental processes.

Pavlov, Watson, Skinner, and Behaviorism

Early work in the field of behavior was conducted by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936). Pavlov studied a form of learning behavior called a conditioned reflex, in which an animal or human produced a reflex (unconscious) response to a stimulus and, over time, was conditioned to produce the response to a different stimulus that the experimenter associated with the original stimulus. The reflex Pavlov worked with was salivation in response to the presence of food. The salivation reflex could be elicited using a second stimulus, such as a specific sound, that was presented in association with the initial food stimulus several times. Once the response to the second stimulus was “learned,” the food stimulus could be omitted. Pavlov’s “classical conditioning” is only one form of learning behavior studied by behaviorists.

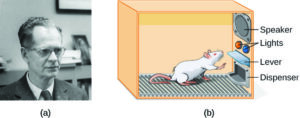

John B. Watson (1878–1958) was an influential American psychologist whose most famous work occurred during the early 20th century at Johns Hopkins University (Figure 1.2.4). While Wundt and James were concerned with understanding conscious experience, Watson thought that the study of consciousness was flawed. Because he believed that objective analysis of the mind was impossible, Watson preferred to focus directly on observable behavior and try to bring that behavior under control. Watson was a major proponent of shifting the focus of psychology from the mind to behavior, and this approach of observing and controlling behavior came to be known as behaviorism. A major object of study by behaviorists was learned behavior and its interaction with inborn qualities of the organism. Behaviorism commonly used animals in experiments under the assumption that what was learned using animal models could, to some degree, be applied to human behavior. Indeed, Tolman (1938) stated, “I believe that everything important in psychology (except … such matters as involve society and words) can be investigated in essence through the continued experimental and theoretical analysis of the determiners of rat behavior at a choice-point in Behaviorism dominated experimental psychology for several decades, and its influence can still be felt today (Thorne & Henley, 2005). Behaviorism is largely responsible for establishing psychology as a scientific discipline through its objective methods and especially experimentation. In addition, it is used in behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behavior modification is commonly used in classroom settings. Behaviorism has also led to research on environmental influences on human behavior.

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) was an American psychologist (Figure 1.2.5). Like Watson, Skinner was a behaviorist, and he concentrated on how behavior was affected by its consequences. Therefore, Skinner spoke of reinforcement and punishment as major factors in driving behavior. As a part of his research, Skinner developed a chamber that allowed the careful study of the principles of modifying behavior through reinforcement and punishment. This device, known as an operant conditioning chamber (or more familiarly, a Skinner box), has remained a crucial resource for researchers studying behavior (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

modification of work by “Silly rabbit”/Wikimedia Commons

The Skinner box is a chamber that isolates the subject from the external environment and has a behavior indicator such as a lever or a button. When the animal pushes the button or lever, the box is able to deliver a positive reinforcement of the behavior (such as food) or a punishment (such as a noise) or a token conditioner (such as a light) that is correlated with either the positive reinforcement or punishment.

Skinner’s focus on positive and negative reinforcement of learned behaviors had a lasting influence in psychology that has waned somewhat since the growth of research in cognitive psychology. Despite this, conditioned learning is still used in human behavioral modification. Skinner’s two widely read and controversial popular science books about the value of operant conditioning for creating happier lives remain as thought-provoking arguments for his approach (Greengrass, 2004).

Maslow, Rogers, and Humanism

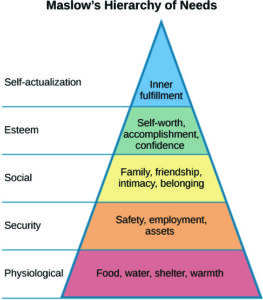

During the early 20th century, American psychology was dominated by behaviorism and psychoanalysis. However, some psychologists were uncomfortable with what they viewed as limited perspectives being so influential to the field. They objected to the pessimism and determinism (all actions driven by the unconscious) of Freud. They also disliked the reductionism, or simplifying nature, of behaviorism. Behaviorism is also deterministic at its core, because it sees human behavior as entirely determined by a combination of genetics and environment. Some psychologists began to form their own ideas that emphasized personal control, intentionality, and a true predisposition for “good” as important for our self-concept and our behavior. Thus, humanism emerged. Humanism is a perspective within psychology that emphasizes the potential for good that is innate to all humans. Two of the most well-known proponents of humanistic psychology are Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers (O’Hara, n.d.).

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) was an American psychologist who is best known for proposing a hierarchy of human needs in motivating behavior (Figure 1.2.6). Although this concept will be discussed in more detail in a later chapter, a brief overview will be provided here. Maslow asserted that so long as basic needs necessary for survival were met (e.g., food, water, shelter), higher-level needs (e.g., social needs) would begin to motivate behavior. According to Maslow, the highest-level needs relate to self-actualization, a process by which we achieve our full potential. Obviously, the focus on the positive aspects of human nature that are characteristic of the humanistic perspective is evident (Thorne & Henley, 2005). Humanistic psychologists rejected, on principle, the research approach based on reductionist experimentation in the tradition of the physical and biological sciences, because it missed the “whole” human being. Beginning with Maslow and Rogers, there was an insistence on a humanistic research program. This program has been largely qualitative (not measurement-based), but there exist a number of quantitative research strains within humanistic psychology, including research on happiness, self-concept, meditation, and the outcomes of humanistic psychotherapy (Friedman, 2008).

Carl Rogers (1902–1987) was also an American psychologist who, like Maslow, emphasized the potential for good that exists within all people (Figure 1.2.7). Rogers used a therapeutic technique known as client-centered therapy in helping his clients deal with problematic issues that resulted in their seeking psychotherapy. Unlike a psychoanalytic approach in which the therapist plays an important role in interpreting what conscious behavior reveals about the unconscious mind, client-centered therapy involves the patient taking a lead role in the therapy session. Rogers believed that a therapist needed to display three features to maximize the effectiveness of this particular approach: unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and empathy. Unconditional positive regard refers to the fact that the therapist accepts their client for who they are, no matter what he or she might say. Provided these factors, Rogers believed that people were more than capable of dealing with and working through their own issues (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

“Didius”/Wikimedia Commons

Humanism has been influential to psychology as a whole. Both Maslow and Rogers are well-known names among students of psychology (you will read more about both men later in this text), and their ideas have influenced many scholars. Furthermore, Rogers’ client-centered approach to therapy is still commonly used in psychotherapeutic settings today (O’hara, n.d.)

The Cognitive Revolution

Behaviorism’s emphasis on objectivity and focus on external behavior had pulled psychologists’ attention away from the mind for a prolonged period of time. The early work of the humanistic psychologists redirected attention to the individual human as a whole, and as a conscious and self-aware being. By the 1950s, new disciplinary perspectives in linguistics, neuroscience, and computer science were emerging, and these areas revived interest in the mind as a focus of scientific inquiry. This particular perspective has come to be known as the cognitive revolution (Miller, 2003). By 1967, Ulric Neisser published the first textbook entitled Cognitive Psychology, which served as a core text in cognitive psychology courses around the country (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

Although no one person is entirely responsible for starting the cognitive revolution, Noam Chomsky was very influential in the early days of this movement (Figure 1.2.8). Chomsky (1928–), an American linguist, was dissatisfied with the influence that behaviorism had had on psychology. He believed that psychology’s focus on behavior was short-sighted and that the field had to re-incorporate mental functioning into its purview if it were to offer any meaningful contributions to understanding behavior (Miller, 2003).

Robert Moran

European psychology had never really been as influenced by behaviorism as had American psychology; and thus, the cognitive revolution helped reestablish lines of communication between European psychologists and their American counterparts. Furthermore, psychologists began to cooperate with scientists in other fields, like anthropology, linguistics, computer science, and neuroscience, among others. This interdisciplinary approach often was referred to as the cognitive sciences, and the influence and prominence of this particular perspective resonates in modern-day psychology (Miller, 2003).

Feminist Psychology

The science of psychology has had an impact on human wellbeing, both positive and negative. The dominant influence of Western, white, and male academics in the early history of psychology meant that psychology developed with the biases inherent in those individuals, which often had negative consequences for members of society that were not white or male. Women, members of ethnic minorities in both the United States and other countries, and individuals with sexual orientations other than heterosexual had difficulties entering the field of psychology and therefore influencing its development. They also suffered from the attitudes of white, male psychologists, who were not immune to the nonscientific attitudes prevalent in the society in which they developed and worked. Until the 1960s, the science of psychology was largely a “womanless” psychology (Crawford & Marecek, 1989), meaning that few women were able to practice psychology, so they had little influence on what was studied. In addition, the experimental subjects of psychology were mostly men, which resulted from underlying assumptions that gender had no influence on psychology and that women were not of sufficient interest to study.

An article by Naomi Weisstein, first published in 1968 (Weisstein, 1993), stimulated a feminist revolution in psychology by presenting a critique of psychology as a science. She also specifically criticized male psychologists for constructing the psychology of women entirely out of their own cultural biases and without careful experimental tests to verify any of their characterizations of women. Weisstein used, as examples, statements by prominent psychologists in the 1960s, such as this quote by Bruno Bettleheim: “... we must start with the realization that, as much as women want to be good scientists or engineers, they want first and foremost to be womanly companions of men and to be mothers.” Weisstein’s critique formed the foundation for the subsequent development of a feminist psychology that attempted to be free of the influence of male cultural biases on our knowledge of the psychology of women and, indeed, of both genders.

Crawford & Marecek (1989) identify several feminist approaches to psychology that can be described as feminist psychology. These include re-evaluating and discovering the contributions of women to the history of psychology, studying psychological gender differences, and questioning the male bias present across the practice of the scientific approach to knowledge.

Multicultural Psychology

Culture has important impacts on individuals and social psychology, yet the effects of culture on psychology are under-studied. There is a risk that psychological theories and data derived from white, American settings could be assumed to apply to individuals and social groups from other cultures and this is unlikely to be true (Betancourt & López, 1993). One weakness in the field of cross-cultural psychology is that in looking for differences in psychological attributes across cultures, there remains a need to go beyond simple descriptive statistics (Betancourt & López, 1993). In this sense, it has remained a descriptive science, rather than one seeking to determine cause and effect. For example, a study of characteristics of individuals seeking treatment for a binge eating disorder in Hispanic American, African American, and Caucasian American individuals found significant differences between groups (Franko et al., 2012). The study concluded that results from studying any one of the groups could not be extended to the other groups, and yet potential causes of the differences were not measured.

This history of multicultural psychology in the United States is a long one. The role of African American psychologists in researching the cultural differences between African American individual and social psychology is but one example. In 1920, Cecil Sumner was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in the United States. Sumner established a psychology degree program at Howard University, leading to the education of a new generation of African American psychologists (Black, Spence, and Omari, 2004). Much of the work of early African American psychologists (and a general focus of much work in first half of the 20th century in psychology in the United States) was dedicated to testing and intelligence testing in particular (Black et al., 2004). That emphasis has continued, particularly because of the importance of testing in determining opportunities for children, but other areas of exploration in African-American psychology research include learning style, sense of community and belonging, and spiritualism (Black et al., 2004).

The American Psychological Association has several ethnically based organizations for professional psychologists that facilitate interactions among members. Since psychologists belonging to specific ethnic groups or cultures have the most interest in studying the psychology of their communities, these organizations provide an opportunity for the growth of research on the impact of culture on individual and social psychology.

Contemporary Psychology

Contemporary psychology is a diverse field that is influenced by all of the historical perspectives described in the preceding section. Reflective of the discipline’s diversity is the diversity seen within the American Psychological Association (APA). The APA is a professional organization representing psychologists in the United States. The APA is the largest organization of psychologists in the world, and its mission is to advance and disseminate psychological knowledge for the betterment of people. There are 56 divisions within the APA, representing a wide variety of specialties that range from Societies for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality to Exercise and Sport Psychology to Behavioral Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology. Reflecting the diversity of the field of psychology itself, members, affiliate members, and associate members span the spectrum from students to doctoral-level psychologists, and come from a variety of places including educational settings, criminal justice, hospitals, the armed forces, and industry (American Psychological Association, 2014). The Association for Psychological Science (APS) was founded in 1988 and seeks to advance the scientific orientation of psychology. Its founding resulted from disagreements between members of the scientific and clinical branches of psychology within the APA. The APS publishes five research journals and engages in education and advocacy with funding agencies. A significant proportion of its members are international, although the majority is located in the United States. Other organizations provide networking and collaboration opportunities for professionals of several ethnic or racial groups working in psychology, such as the National Latina/o Psychological Association (NLPA), the Asian American Psychological Association (AAPA), the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi), and the Society of Indian Psychologists (SIP). Most of these groups are also dedicated to studying psychological and social issues within their specific communities.

This section will provide an overview of the major subdivisions within psychology today in the order in which they are introduced throughout the remainder of this textbook. This is not meant to be an exhaustive listing, but it will provide insight into the major areas of research and practice of modern-day psychologists.

Biopsychology and Evolutionary Psychology

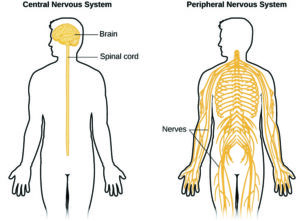

As the name suggests, biopsychology explores how our biology influences our behavior. While biological psychology is a broad field, many biological psychologists want to understand how the structure and function of the nervous system is related to behavior (Figure 1.2.9). As such, they often combine the research strategies of both psychologists and physiologists to accomplish this goal (as discussed in Carlson, 2013).

The research interests of biological psychologists span a number of domains, including but not limited to, sensory and motor systems, sleep, drug use and abuse, ingestive behavior, reproductive behavior, neurodevelopment, plasticity of the nervous system, and biological correlates of psychological disorders. Given the broad areas of interest falling under the purview of biological psychology, it will probably come as no surprise that individuals from all sorts of backgrounds are involved in this research, including biologists, medical professionals, physiologists, and chemists. This interdisciplinary approach is often referred to as neuroscience, of which biological psychology is a component (Carlson, 2013).

While biopsychology typically focuses on the immediate causes of behavior based in the physiology of a human or other animal, evolutionary psychology seeks to study the ultimate biological causes of behavior. To the extent that a behavior is impacted by genetics, a behavior, like any anatomical characteristic of a human or animal, will demonstrate adaption to its surroundings. These surroundings include the physical environment and, since interactions between organisms can be important to survival and reproduction, the social environment. The study of behavior in the context of evolution has its origins with Charles Darwin, the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin was well aware that behaviors should be adaptive and wrote books titled, The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), to explore this field.

Evolutionary psychology, and specifically, the evolutionary psychology of humans, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent decades. To be subject to evolution by natural selection, a behavior must have a significant genetic cause. In general, we expect all human cultures to express a behavior if it is caused genetically, since the genetic differences among human groups are small. The approach taken by most evolutionary psychologists is to predict the outcome of a behavior in a particular situation based on evolutionary theory and then to make observations, or conduct experiments, to determine whether the results match the theory. It is important to recognize that these types of studies are not strong evidence that a behavior is adaptive, since they lack information that the behavior is in some part genetic and not entirely cultural (Endler, 1986). Demonstrating that a trait, especially in humans, is naturally selected is extraordinarily difficult; perhaps for this reason, some evolutionary psychologists are content to assume the behaviors they study have genetic determinants (Confer et al., 2010).

One other drawback of evolutionary psychology is that the traits that we possess now evolved under environmental and social conditions far back in human history, and we have a poor understanding of what these conditions were. This makes predictions about what is adaptive for a behavior difficult. Behavioral traits need not be adaptive under current conditions, only under the conditions of the past when they evolved, about which we can only hypothesize.

There are many areas of human behavior for which evolution can make predictions. Examples include memory, mate choice, relationships between kin, friendship and cooperation, parenting, social organization, and status (Confer et al., 2010).

Evolutionary psychologists have had success in finding experimental correspondence between observations and expectations. In one example, in a study of mate preference differences between men and women that spanned 37 cultures, Buss (1989) found that women valued earning potential factors greater than men, and men valued potential reproductive factors (youth and attractiveness) greater than women in their prospective mates. In general, the predictions were in line with the predictions of evolution, although there were deviations in some cultures.

Sensation and Perception

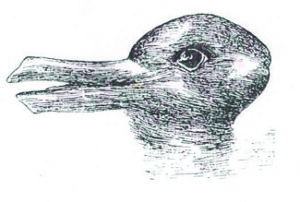

Scientists interested in both physiological aspects of sensory systems as well as in the psychological experience of sensory information work within the area of sensation and perception (Figure 1.2.10). As such, sensation and perception research is also quite interdisciplinary. Imagine walking between buildings as you move from one class to another. You are inundated with sights, sounds, touch sensations, and smells. You also experience the temperature of the air around you and maintain your balance as you make your way. These are all factors of interest to someone working in the domain of sensation and perception.

As described in a later chapter that focuses on the results of studies in sensation and perception, our experience of our world is not as simple as the sum total of all of the sensory information (or sensations) together. Rather, our experience (or perception) is complex and is influenced by where we focus our attention, our previous experiences, and even our cultural backgrounds.

Cognitive Psychology

As mentioned in the previous section, the cognitive revolution created an impetus for psychologists to focus their attention on better understanding the mind and mental processes that underlie behavior. Thus, cognitive psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on studying cognitions, or thoughts, and their relationship to our experiences and our actions. Like biological psychology, cognitive psychology is broad in its scope and often involves collaborations among people from a diverse range of disciplinary backgrounds. This has led some to coin the term cognitive science to describe the interdisciplinary nature of this area of research (Miller, 2003).

Cognitive psychologists have research interests that span a spectrum of topics, ranging from attention to problem solving to language to memory. The approaches used in studying these topics are equally diverse. Given such diversity, cognitive psychology is not captured in one chapter of this text per se; rather, various concepts related to cognitive psychology will be covered in relevant portions of the chapters in this text on sensation and perception, thinking and intelligence, memory, lifespan development, social psychology, and therapy.

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of development across a lifespan. Developmental psychologists are interested in processes related to physical maturation. However, their focus is not limited to the physical changes associated with aging, as they also focus on changes in cognitive skills, moral reasoning, social behavior, and other psychological attributes.

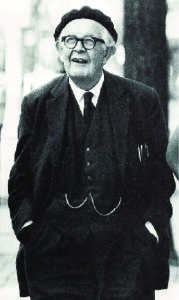

Early developmental psychologists focused primarily on changes that occurred through reaching adulthood, providing enormous insight into the differences in physical, cognitive, and social capacities that exist between very young children and adults. For instance, research by Jean Piaget (Figure 1.2.11) demonstrated that very young children do not demonstrate object permanence. Object permanence refers to the understanding that physical things continue to exist, even if they are hidden from us. If you were to show an adult a toy, and then hide it behind a curtain, the adult knows that the toy still exists. However, very young infants act as if a hidden object no longer exists. The age at which object permanence is achieved is somewhat controversial (Munakata, McClelland, Johnson, and Siegler, 1997).

While Piaget was focused on cognitive changes during infancy and childhood as we move to adulthood, there is an increasing interest in extending research into the changes that occur much later in life. This may be reflective of changing population demographics of developed nations as a whole. As more and more people live longer lives, the number of people of advanced age will continue to increase. Indeed, it is estimated that there were just over 40 million people aged 65 or older living in the United States in 2010. However, by 2020, this number is expected to increase to about 55 million. By the year 2050, it is estimated that nearly 90 million people in this country will be 65 or older (Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

Personality Psychology

Personality psychology focuses on patterns of thoughts and behaviors that make each individual unique. Several individuals (e.g., Freud and Maslow) that we have already discussed in our historical overview of psychology, and the American psychologist Gordon Allport, contributed to early theories of personality. These early theorists attempted to explain how an individual’s personality develops from his or her given perspective. For example, Freud proposed that personality arose as conflicts between the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind were carried out over the lifespan. Specifically, Freud theorized that an individual went through various psychosexual stages of development. According to Freud, adult personality would result from the resolution of various conflicts that centered on the migration of erogenous (or sexual pleasure-producing) zones from the oral (mouth) to the anus to the phallus to the genitals. Like many of Freud’s theories, this particular idea was controversial and did not lend itself to experimental tests (Person, 1980).

More recently, the study of personality has taken on a more quantitative approach. Rather than explaining how personality arises, research is focused on identifying personality traits, measuring these traits, and determining how these traits interact in a particular context to determine how a person will behave in any given situation. Personality traits are relatively consistent patterns of thought and behavior, and many have proposed that five trait dimensions are sufficient to capture the variations in personality seen across individuals. These five dimensions are known as the “Big Five” or the Five Factor model, and include dimensions of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion (Figure 1.2.12). Each of these traits has been demonstrated to be relatively stable over the lifespan (e.g., Rantanen, Metsäpelto, Feldt, Pulkinnen, and Kokko, 2007; Soldz & Vaillant, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 2008) and is influenced by genetics (e.g., Jang, Livesly, and Vernon, 1996).

Social Psychology

Social psychology focuses on how we interact with and relate to others. Social psychologists conduct research on a wide variety of topics that include differences in how we explain our own behavior versus how we explain the behaviors of others, prejudice, and attraction, and how we resolve interpersonal conflicts. Social psychologists have also sought to determine how being among other people changes our own behavior and patterns of thinking.

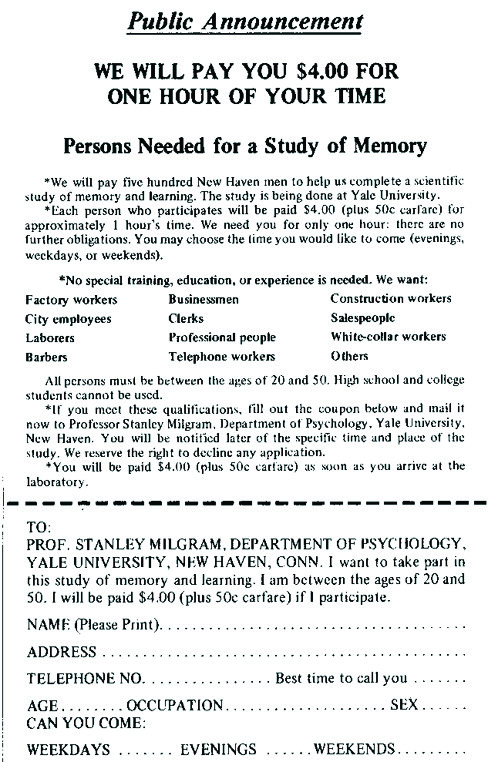

There are many interesting examples of social psychological research, and you will read about many of these in a later chapter of this textbook. Until then, you will be introduced to one of the most controversial psychological studies ever conducted. Stanley Milgram was an American social psychologist who is most famous for research that he conducted on obedience. After the holocaust, in 1961, a Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, who was accused of committing mass atrocities, was put on trial. Many people wondered how German soldiers were capable of torturing prisoners in concentration camps, and they were unsatisfied with the excuses given by soldiers that they were simply following orders. At the time, most psychologists agreed that few people would be willing to inflict such extraordinary pain and suffering, simply because they were obeying orders. Milgram decided to conduct research to determine whether or not this was true (Figure 1.2.13). As you will read later in the text, Milgram found that nearly two-thirds of his participants were willing to deliver what they believed to be lethal shocks to another person, simply because they were instructed to do so by an authority figure (in this case, a man dressed in a lab coat). This was in spite of the fact that participants received payment for simply showing up for the research study and could have chosen not to inflict pain or more serious consequences on another person by withdrawing from the study. No one was actually hurt or harmed in any way, Milgram’s experiment was a clever ruse that took advantage of research confederates, those who pretend to be participants in a research study who are actually working for the researcher and have clear, specific directions on how to behave during the research study (Hock, 2009). Milgram’s and others’ studies that involved deception and potential emotional harm to study participants catalyzed the development of ethical guidelines for conducting psychological research that discourage the use of deception of research subjects, unless it can be argued not to cause harm and, in general, requiring informed consent of participants.

Industrial-organizational Psychology

Industrial-Organizational psychology (I-O psychology) is a subfield of psychology that applies psychological theories, principles, and research findings in industrial and organizational settings. I-O psychologists are often involved in issues related to personnel management, organizational structure, and workplace environment. Businesses often seek the aid of I-O psychologists to make the best hiring decisions as well as to create an environment that results in high levels of employee productivity and efficiency. In addition to its applied nature, I-O psychology also involves conducting scientific research on behavior within I-O settings (Riggio, 2013).

Health Psychology

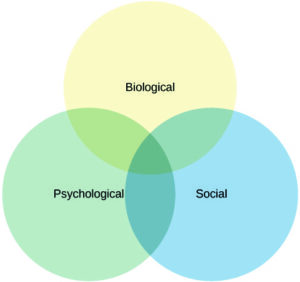

Health psychology focuses on how health is affected by the interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. This particular approach is known as the biopsychosocial model (Figure 1.2.14). Health psychologists are interested in helping individuals achieve better health through public policy, education, intervention, and research. Health psychologists might conduct research that explores the relationship between one’s genetic makeup, patterns of behavior, relationships, psychological stress, and health. They may research effective ways to motivate people to address patterns of behavior that contribute to poorer health (MacDonald, 2013).

Sport and Exercise Psychology

Researchers in sport and exercise psychology study the psychological aspects of sport performance, including motivation and performance anxiety, and the effects of sport on mental and emotional wellbeing. Research is also conducted on similar topics as they relate to physical exercise in general. The discipline also includes topics that are broader than sport and exercise but that are related to interactions between mental and physical performance under demanding conditions, such as fire fighting, military operations, artistic performance, and surgery.

Clinical Psychology

Clinical psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic patterns of behavior. As such, it is generally considered to be a more applied area within psychology; however, some clinicians are also actively engaged in scientific research. Counseling psychology is a similar discipline that focuses on emotional, social, vocational, and health-related outcomes in individuals who are considered psychologically healthy.

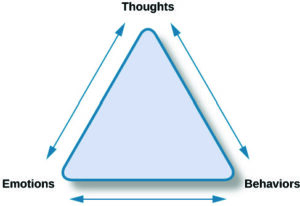

As mentioned earlier, both Freud and Rogers provided perspectives that have been influential in shaping how clinicians interact with people seeking psychotherapy. While aspects of the psychoanalytic theory are still found among some of today’s therapists who are trained from a psychodynamic perspective, Roger’s ideas about client-centered therapy have been especially influential in shaping how many clinicians operate. Furthermore, both behaviorism and the cognitive revolution have shaped clinical practice in the forms of behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (Figure 1.2.15). Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and problematic patterns of behavior will be discussed in detail in later chapters of this textbook.

By far, this is the area of psychology that receives the most attention in popular media, and many people mistakenly assume that all psychology is clinical psychology.

Forensic Psychology

Forensic psychology is a branch of psychology that deals questions of psychology as they arise in the context of the justice system. For example, forensic psychologists (and forensic psychiatrists) will assess a person’s competency to stand trial, assess the state of mind of a defendant, act as consultants on child custody cases, consult on sentencing and treatment recommendations, and advise on issues such as eyewitness testimony and children’s testimony (American Board of Forensic Psychology, 2014). In these capacities, they will typically act as expert witnesses, called by either side in a court case to provide their research- or experience-based opinions. As expert witnesses, forensic psychologists must have a good understanding of the law and provide information in the context of the legal system rather than just within the realm of psychology. Forensic psychologists are also used in the jury selection process and witness preparation. They may also be involved in providing psychological treatment within the criminal justice system. Criminal profilers are a relatively small proportion of psychologists that act as consultants to law enforcement.

References

American Board of Forensic Psychology. (2014). Brochure. Retrieved from http://www.abfp.com/brochure.asp

American Psychological Association. (2014). Retrieved from www.apa.org

Betancourt, H., & López, S. R. (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48, 629–637.

Black, S. R., Spence, S. A., & Omari, S. R. (2004). Contributions of African Americans to the field of psychology. Journal of Black Studies, 35, 40–64.

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 1–49.

Carlson, N. R. (2013). Physiology of Behavior (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Confer, J. C., Easton, J. A., Fleischman, D. S., Goetz, C. D., Lewis, D. M. G., Perilloux, C., & Buss, D. M. (2010). Evolutionary psychology. Controversies, questions, prospects, and limitations. American Psychologist, 65, 100–126.

Crawford, M., & Marecek, J. (1989). Psychology reconstructs the female 1968–1988. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 13, 147–165.

Danziger, K. (1980). The history of introspection reconsidered. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 16, 241–262.

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Projected future growth of the older population. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/future_growth/future_growth.aspx#age

Endler, J. A. (1986). Natural Selection in the Wild. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Franko, D. L., et al. (2012). Racial/ethnic differences in adults in randomized clinical trials of binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 186–195.

Friedman, H. (2008), Humanistic and positive psychology: The methodological and epistemological divide. The Humanistic Psychologist, 36, 113–126.

Gordon, O. E. (1995). A brief history of psychology. Retrieved from http://www.psych.utah.edu/gordon/Classes/Psy4905Docs/PsychHistory/index.html#maptop

Greengrass, M. (2004). 100 years of B.F. Skinner. Monitor on Psychology, 35, 80.

Hock, R. R. (2009). Social psychology. Forty studies that changed psychology: Explorations into the history of psychological research (pp. 308–317). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Jang, K. L., Livesly, W. J., & Vernon, P. A. (1996). Heritability of the Big Five personality dimensions and their facets: A twin study. Journal of Personality, 64, 577–591.

Knekt, P. P., et al. (2008). Randomized trial on the effectiveness of long- and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and solution-focused therapy on psychiatric symptoms during a 3-year follow-up. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research In Psychiatry And The Allied Sciences, 38, 689–703.

Macdonald, C. (2013). Health psychology center presents: What is health psychology? Retrieved from http://healthpsychology.org/what-is-health-psychology/

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. (2008). Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. In G. J. Boyle, G. Matthews, & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), The Sage handbook of personality theory and assessment. Vol. 1 Personality theories and models. London: Sage.

Miller, G. A. (2003). The cognitive revolution: A historical perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 141–144.

Munakata, Y., McClelland, J. L., Johnson, M. H., & Siegler, R. S. (1997). Rethinking infant knowledge: Toward an adaptive process account of successes and failures in object permanence tasks. Psychological Review, 104, 689–713.

Nicolas, S., & Ferrand, L. (1999). Wundt’s laboratory at Leipzig in 1891. History of Psychology, 2, 194–203.

O’Hara, M. (n.d.). Historic review of humanistic psychology. Retrieved from http://www.ahpweb.org/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&layout=item&id=14&Itemid=24

Person, E. S. (1980). Sexuality as the mainstay of identity: Psychoanalytic perspectives. Signs, 5, 605–630.

Rantanen, J., Metsäpelto, R. L., Feldt, T., Pulkkinen, L., & Kokko, K. (2007). Long-term stability in the Big Five personality traits in adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 511–518.

Riggio, R. E. (2013). What is industrial/organizational psychology? Psychology Today. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/cutting-edge-leadership/201303/what-is-industrialorganizational-psychology

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98–109.

Soldz, S., & Vaillant, G. E. (1999). The Big Five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 208–232.

Thorne, B. M., & Henley, T. B. (2005). Connections in the history and systems of psychology (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Tolman, E. C. (1938). The determiners of behavior at a choice point. Psychological Review, 45, 1–41.

Weisstein, N. (1993). Psychology constructs the female: Or, the fantasy life of the male psychologist (with some attention to the fantasies of his friends, the male biologist and the male anthropologist). Feminism and Psychology, 3, 195–210.

Westen, D. (1998). The scientific legacy of Sigmund Freud, toward a psychodynamically informed psychological science. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 333–371.