1 Chapter 1: African-American Music

Blues, Blood, and a Backbeat

Chapter 1

Introduction

The question posed in the article for this chapter is, simply, where did the blues come from? In other words, what are the roots of the blues? The blues, and all of American music, comes from many sources, and the roots of the blues have to do with the ways in which Africans, most of whom came as slaves, came to the United States, the first arriving in 1619, and how their music developed, evolved, and mixed with music from other sources. The uniqueness of the blues as an American art form has to do with the ways that African and Colonial music and culture came together, combined, and formed the hybrid that is African-American music. Many musical traditions came out of this hybridity, including music of worship, music of work, minstrelsy, ragtime and the blues.

African-American Music

The roots of African-American music are international and come from three distinct musical traditions: art music from Europe, folk music from the British Isles, and West African music traditions. European art, or classical, music came to the New World with the European colonists from several parts of Europe. Among the most heard traditions were art song and opera arias. These songs, many originally in German, Italian and French, were often translated and simplified for the middle and lower classes. Most popular songs published in the United States before the Civil War were based on European classical music.

Another source of music in early America was folk music from the British Isles. The large numbers of immigrants from England, Scotland, and Ireland brought with them a variety of popular music traditions, including fiddle tunes, songs, and ballads that rapidly became part of the American repertory. These folk songs were different than the urban popular music heard in places like New York and Boston and were mostly heard in rural settings, where large numbers of these British immigrants found themselves. Many traditions in American music are drawn from this folk music, most importantly minstrelsy, which we will see was an important part of the development of popular music in the United States during the 19th century.

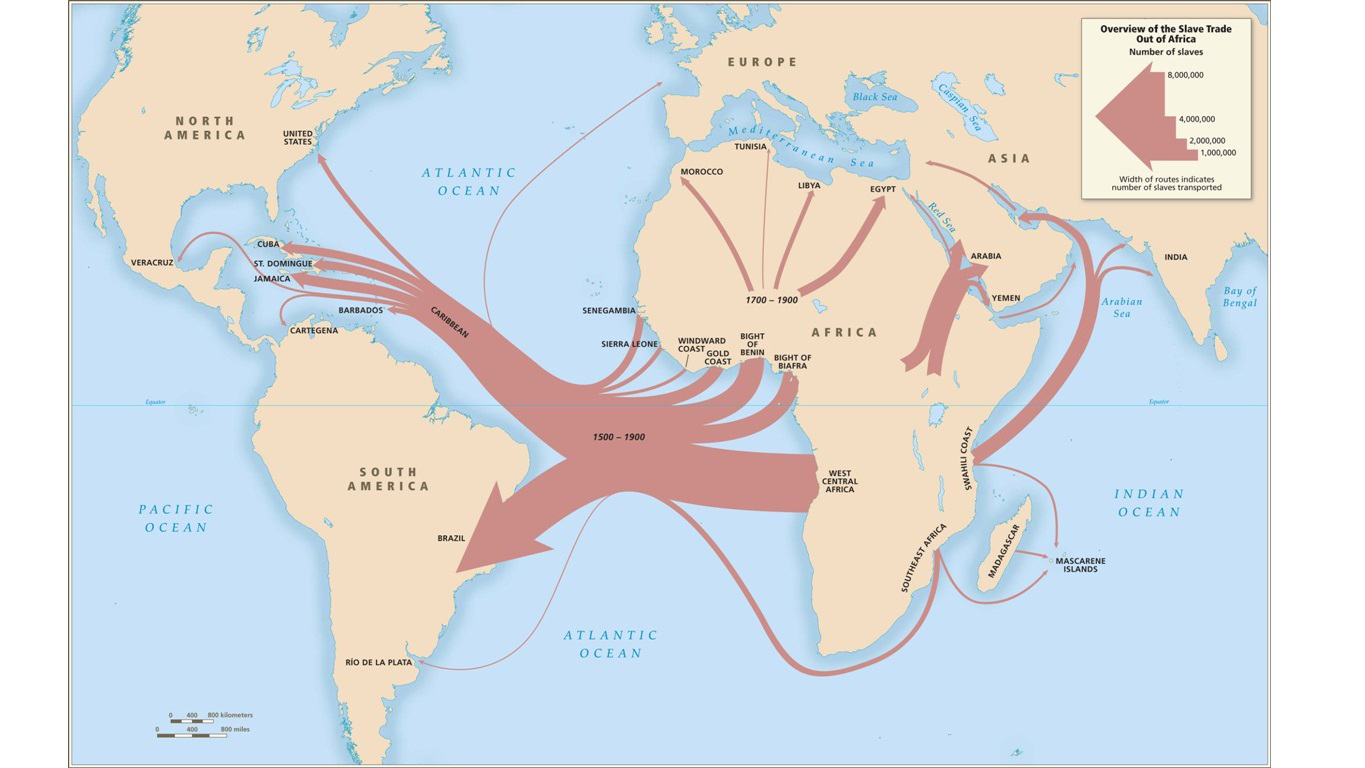

Many of the important roots of American popular music come from African sources. Slaves came to United States directly and indirectly from Africa. Those that came directly from Africa came from places such as the Gold Coast (what is now Nigeria, the Ivory Coast, etc.), from the Congo area, and from farther south in what is now the area around Angola, bringing with them many aspects of their music cultures. Other musical traditions came to North America indirectly from the Caribbean, with slaves who then made up part of the triangle trade between the Caribbean, North America, and England. Because slaves came from multiple regions of Africa, many different musical traditions came with them.

The result of these different sources of the popular music was a musical cross-pollination that is unique to the United States and distinguishes American popular music from African and European traditions. The one aspect of this combined music was backbeat, the rhythmic feature that is a distinguishing characteristic for American popular music styles since the turn of the 20th century. Popular music throughout the Americas can be said to have a similar cross-pollination, but what distinguishes all of the music traditions in the Americas is the different ways in which colonial and enslaved cultures interacted. American music, as a result of these different sources, is a hybrid that joins characteristics from different African and European sources. This does not mean that European musical traditions were abandoned, and indeed European classical and folk music remained vibrant throughout the colonial period and in the early independent American states.

Although slavery was common to most parts of the Americas, treatment of slaves was not the same. Unlike countries with larger slave populations, such as Brazil and Cuba, in North America, Africans were not able to keep their musical traditions intact. Family groups and language groups were often separated in this country, which was not so in other colonies. To put these differences in perspective, the number of slaves taken to colonial North America was somewhere in the order of half a million; the number of slaves taken to the West Indies was around four million; and in Brazil, the number was something more than five million. These differences reflect, among other forces and factors, the fact that Brazil and the West Indies were much closer to Africa, and, therefore, it was much more economical to transport large numbers of slaves to these places. This resulted in a different colonial-African cultural interaction, which, in turn, resulted in unique musical practices throughout the Americas. Despite this suppression of African cultural practices that took place in North America, African musical values surfaced in American popular music primarily through rhythm.

The African musical heritage is an important part of American popular music. Indeed, African rhythm permeates American popular music, and the steady increase of the influence of African musical values is remarkable. The result is that African-American musical roots dominate American popular music. Truly remarkable is that this is the first time in history that a minority population has shaped the dominant music of the society. This is all the more remarkable in that so much African culture was suppressed in the United States: African slaves were not permitted to practice their musical traditions on American plantations, and African-Americans of different backgrounds and mother languages created their own distinctive musical traditions.

Many West African musical systems contributed to the unique sound of American popular music in terms of vocal timbre, rhythm, and melodic shape. Many African music languages are tonal, meaning that the same syllable may have different meanings depending on pitch and inflection, which results in spoken languages that often approaching song. West African vocal music is very similar in many ways to African American blues in its basic sound. The melodic shape for both the blues and African music is commonly from high to low, and in both there is rhythmic freedom of delivery. Scales and pitch choice in the blues and West African song both often feature melismas, long, florid melodic fragments.

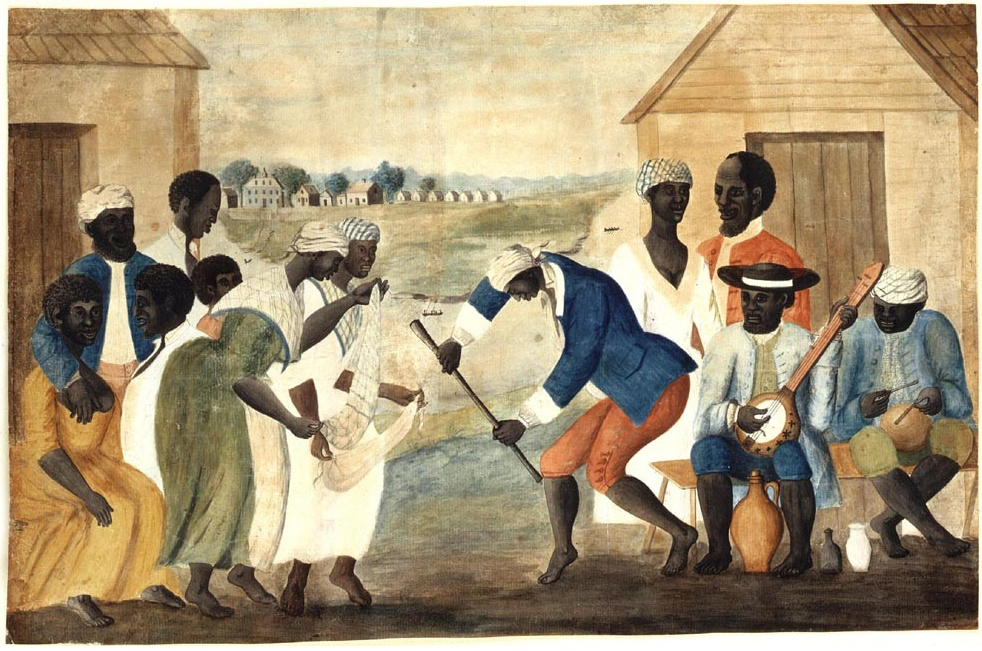

African music also contributed to American music in terms of instruments. Percussion instruments of all shapes and sizes came to the Americas with African slaves. Drums are perhaps the most important, and there are many different types and techniques. Cowbells and other instruments, such as shakers and scratchers, also came from Africa. The African approach to instrumental style also had a profound impact on American popular music in two ways. One is the distinctive sound that many African American performers achieve on various instruments. The other is through experimentation with alternative sounds and instruments, such as the washtub bass, the knife and plate, spoons, and even scratching in hip-hop. One of the most important African American instruments is an adaptation of West African guitar-like instruments, such as the banjar, a gourd guitar adapted to what we now call the banjo.

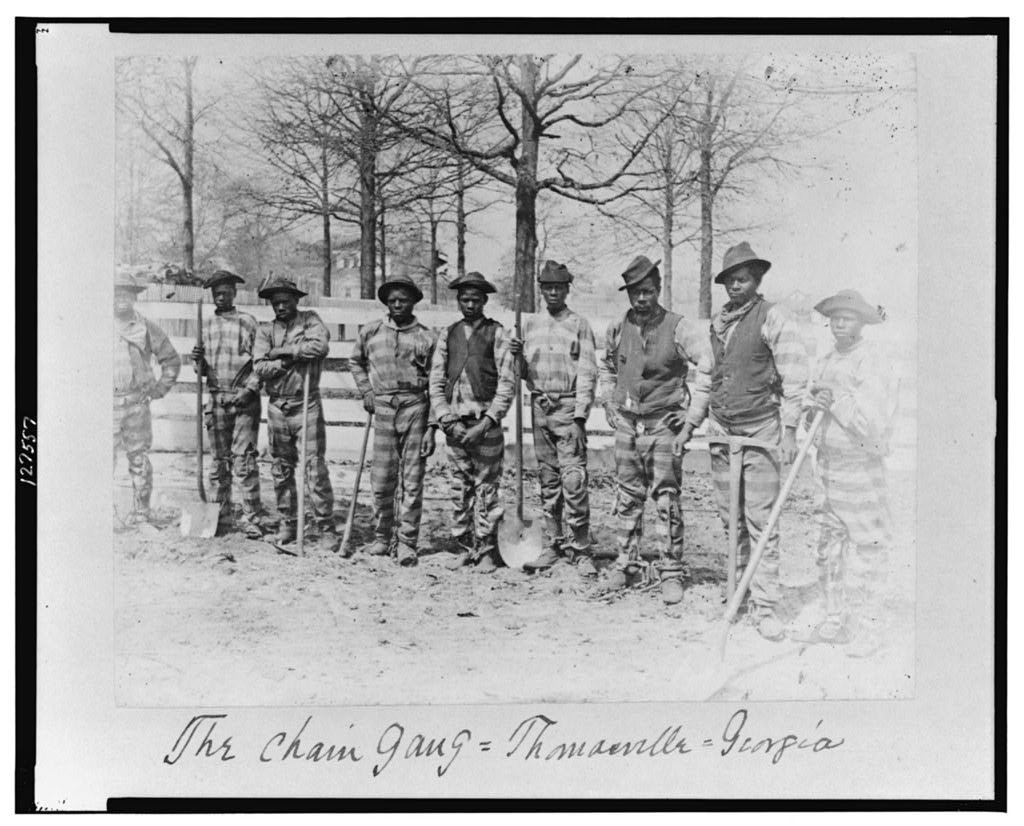

Music of Work

Call and response, a practice in which one person sings a musical phrase which is answered by other singers, is present in other African-American musical traditions, including the music of work. African-derived work songs were widely reported among black slaves in the West Indies in the 18th century and in North America in the 19th century (Titon 2009, 157). They were probably present throughout colonial times as well. Although there is little documentary evidence to this, the use of work songs was widespread in Africa and in Europe, continuing well-established work-song traditions. A typical and well-known African-American work song is “Rosie,” typically sung by prison chain gangs throughout the South.

These songs have many of the same characteristics of other African-American genres, most importantly the blues: they feature call and response, have similar singing styles, have similar rhythms, and use similar melodic ideas, including blue scales and blue notes, and include improvisation.

Music of Worship

A part of the African-American musical tradition that had a great impact on subsequent genres, and continues to influence popular music, is music of worship. One of the most unique aspects of this musical tradition is call and response, a performance practice common in many West African musical traditions that found its way into many popular practices as well. An interesting type of call and response is called lining out, a practice in which the song leader starts and the congregation follows immediately. It was standard procedure in colonial America, not only in African-American worship, but in other worship practices as well. This makes sense considering the population of most churches was illiterate, and this was a way to learn the music with no training. African-American church music also shares singing style, vocal quality, and melodic ornamentation with secular traditions such as the blues.

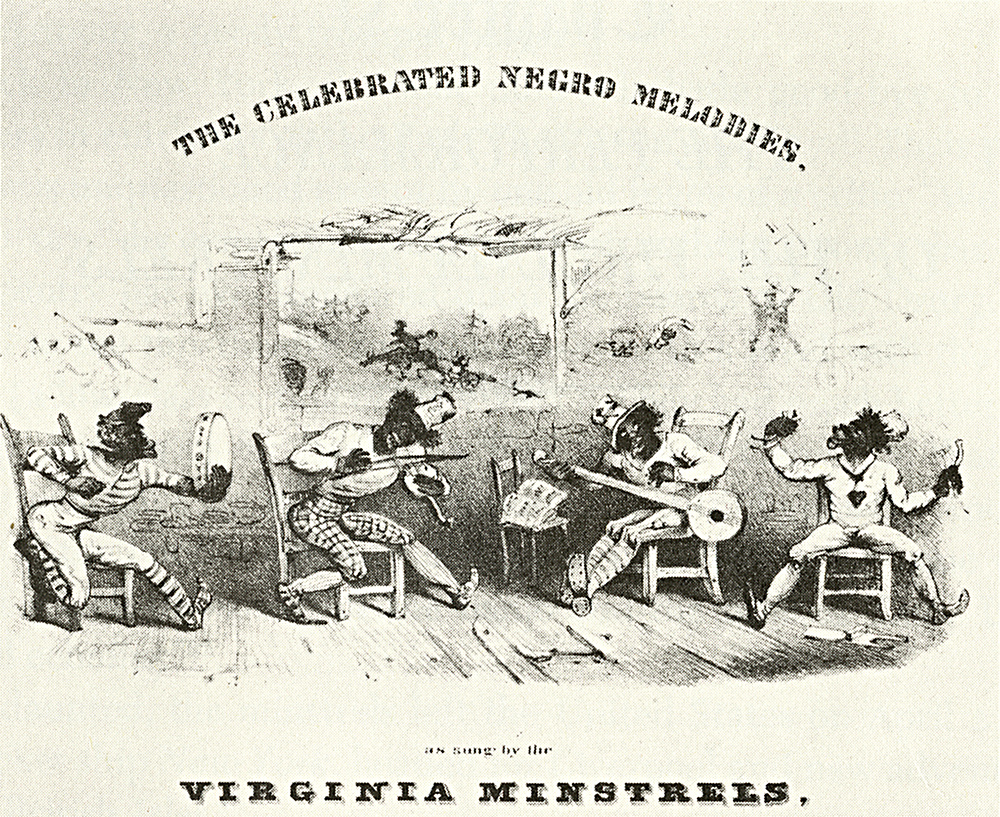

The Minstrel Show

One of the most important 19th century popular musical traditions was the minstrel show, which had its roots in medieval European culture. The American version of minstrelsy was a new and uniquely American genre, an American entertainment and recognized as so. It was popular and home grown and featured many folk elements, humor, and a lack of pretension. The European models were still important, but America minstrelsy was an American style, by Americans, and for an American market. The American minstrel show appeared at a time in which there was a political shift from the eastern, wealthy aristocracy to a more populist sentiment, best reflected in the presidency of Andrew Jackson. The minstrel show of the 1840s and 50s reflected this political change. Minstrel shows were informal, humorous, vigorous, and not stuffy, which was very much not aristocratic. At the same time, it was crude, cool, and a vicious portrayal of African-American culture, most apparent in the fact that most performers in the early shows were white and performed in blackface. This blackface reflected Jacksonian values; it was the best and worst of American populism.

Blackface as an impersonation of African Americans had been around for a long time when the first minstrel shows appeared in 1840s. These shows often featured a stereotypical city slicker and a country bumpkin, known respectively as Zip Coon and Jim Crow. The first minstrel show was in 1843 in New York, featuring a group that call themselves the Virginia Minstrels, all of whom where northerners and white.

These minstrels performed in blackface in a parody or caricature of black performers. None of these performers had ever been to the South and quite probably knew very few if any black performers. This did not stop their caricature of African Americans and African-American culture.

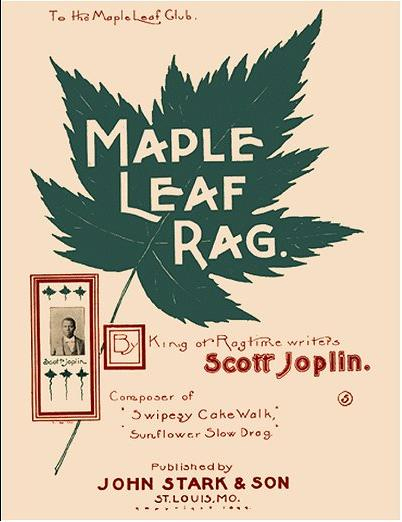

Ragtime songs also became popular in the early part of the century. They tended to be less rhythmically complex than instrumental ragtime and were sung by both African-American and white performers. Many became so popular that they were often interpolated, or substituted, into Broadway shows. Although ragtime was originally part of Midwest and Mississippi Valley saloon culture and featured a great deal of interaction between performers and the audience, as it evolved, it became more appropriate in other venues and became popular throughout the country.

The Blues

The most important and influential African-American musical tradition which influenced American and world music throughout the 20th century and beyond is the blues. Defining the blues can be tricky. It is different and separate from jazz, not a subset. The blues is “a feeling … as well as a specific musical form” (Titon 2009, 165), although jazz musicians often play the blues, and it influenced much jazz. Jazz musicians applied their technique to the blues, but the blues did not lose its identity. The blues are more than just a significant part of black music culture, but rather have become firmly embedded in the musical culture of the United States and the world.

What are the blues? Many characteristics can be found in most blues songs:

- The blues are a specific form: 12 bars with a basic three-chord progression;

- They feature a three- or four-line stanza of poetry;

- There is much rhythmic crossing between the vocal part and the accompaniment, resulting in both polyrhythm and polymeter;

- There is often an element of call and response between the vocal and instrumental parts;

- The blues features a great deal of improvisation, both poetically and musically;

- The blues use scales beyond the diatonic scale, often referred to as blues scales, and performers often sing slightly out of tune as ornamentation to the melodic line, known as blue notes;

- The blues feature an element of swing in which the beat is not symmetrically divided, resulting in a lilting feeling.

The blues first appeared around the turn of the 20th century, and early blues are connected to minstrelsy because many of the early blues musicians were minstrels. An example is Ma Rainey, a famous minstrel who toured the southern United States. Another early performer was Bessie Smith, who was one of the first to record the blues as well.

The blues had a great impact on other American musical forms, including jazz, bluegrass, rock and roll and others. By the 1950s the blues had become old fashioned in the African-American community, and outside the blues strongholds such as the Mississippi Delta, Chicago, and St. Louis, it was somewhat marginalized. The blues enjoyed a strong revival in the 1960s, when it was embraced by many of the great mainstream African-American performers such as Ray Charles, B.B. King (Blues Boy King), James Brown, Aretha Franklin, John Lee Hooker and many others. It remains one of the most important musical genres in the United States and the world.

The blues and the genres that developed from the blues are the most important and recognizable aspects of American popular music. The blues, rock and roll, jazz, ragtime, rap and other musical genres that continue the legacy of African-American music have had great influence on popular music throughout the world. As will be seen in this anthology, these genres have driven the development of popular music on a global scale, and there are many musical traditions throughout the world that are strongly connected to this uniquely American music. This has resulted in a rich, vibrant global music scene, much of which owes a debt to African-American music.

Reading 1.1

The reading for this chapter, “The Roots of the Blues: 1916–1919,” discusses the early blues, covering in depth how the blues came to be and including the African music traits that makes the unique genre that is the blues. The author touches on other African-American music, including details about each genre and how it contributed to the development of American music, both at home and on the world stage. The blues resulted from the social, economic, and racial makeup of the South after the Civil War and Reconstruction, and an understanding of these social conditions helps bring the development of the blues into focus.