2 Reading 1.1: The Roots of the Blues

1619–1919

Reading 1.1

This chapter will introduce us to the blues in various ways. First, we will trace the history of the blues, from their African American roots through various nineteenth-century African American musical styles, including worksongs, spirituals, and popular “minstrel” songs. We will then examine the social conditions at the time of the birth of the blues, and how these conditions influenced the new musical form. We will take a look at some early outgrowths from blues, including ragtime and the beginnings of jazz. We will then briefly examine the typical structure of a blues song. Finally, for those interested in playing blues music, we will give some basic pointers about how to learn to perform them.

History and Origins of the Blues

Where did the blues come from? When did they start, and where did they first appear? The blues are an African American form, so it is natural to seek the answers to these questions in the history of how Africans came to the United States, and what music they brought with them.

|

1619 |

First slaves brought to United States |

|

1781 |

United States defeated British, became an independent nation |

|

1803 |

Through Louisiana Purchase from France, United States, doubled its size, acquired Louisiana and extended western frontiers all the way to Rocky Mountains |

|

1808 |

Congress legislated an end to the slave trade |

|

1847 |

United States defeated Mexico, acquired area from Texas through California |

|

1861 |

Civil War began |

|

1863 |

Lincoln freed the slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation |

|

1865 |

Civil War ended; Reconstruction began |

|

1867 |

Slave Songs of the United States published |

|

1877 |

Reconstruction ended when federal troops withdrawn from South |

|

1890–1910 |

Various racist laws passed restricting African Americans from voting, and from eating or traveling with whites. Number of lynchings increased. |

|

1899 |

Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” published |

|

1902 |

First recording of black music issued by Victor Records: “Camp Meeting Shouts” |

|

1903 |

W.C. Handy saw bluesman playing guitar with a knife at Mississippi train station |

|

1909 |

Founding of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People)

|

|

1910 |

The Journal of American Folklore published extensive article by Howard Odum that included numerous blues texts collected in Georgia, 1906–1908 |

|

1912 |

First sheet music publication of blues songs |

|

1914 |

World War I began |

|

1917 |

United States entered the war First jazz recording by white Original Dixieland Jazz Band |

|

1919 |

Race riots took place in Chicago, Charleston, S.C., East St. Louis, Houston, and in many other major U.S. cities |

Most Africans came to the United States as slaves. The first slaves were brought here in 1619, and the slave trade lasted until 1809, with the illegal importation of slaves continuing up until the Civil War. It is generally acknowledged that most of the slaves imported into the United States came from West Africa, although many different tribes and languages were represented. Although there are no absolutely reliable estimates of how many slaves were brought in illegally, one estimate puts the number at 54,000. However, the precise number of Africans removed from their homes is a matter of some controversy and conjecture. We know that for every slave who reached the United States many died in the inhuman and overcrowded conditions aboard the slave ships. Some committed suicide, throwing themselves overboard rather than accepting life as slaves.

Some of the ship captains actually compelled the slaves to sing and dance on the slave ships—believing that the exercise from dancing would help keep them healthy during the dangerous trip—and we have reports that some of these songs appeared to be laments about the exile of the slaves. Slaves were not allowed to bring instruments from Africa, so the music on board the ships was entirely vocal music. The slaves were brought up on deck, and although they were kept in chains in order to avoid any form of protest or revolt, they were encouraged to dance. At times, they were even whipped if they did not dance. It is presumed that some musical instruments came over with their owners, but we do not know exactly what these instruments were. We do know that the playing of drums, certainly common in virtually every African tribe, was discouraged by the slave owners. There are reports of slaves playing the fiddle or the banjo in various eighteenth-century journals, and paintings that show slaves playing banjos. Cecilia Conway, in her book African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia, lists 12 references to black banjoists prior to 1800, and another 21 references printed by 1856. Dena Epstein, in her book Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War, reports references to slaves playing the fiddle as early as the 1690s, and references to slave banjoists date back to 1754 and 1774. She also writes that simple flutes like quills and pipes were used, and that by the eighteenth-century black fiddlers were a normal part of the musical scene on the plantation. Obviously, the slave musicians also entertained their own people when not performing for the whites.

In his book Savannah Syncopators, Paul Oliver mentions that Robert Winans examined the slave narratives collected by the Work Progress Administration (WPA) during the 1930s. Winans found 295 references by ex-slaves to fiddle players, 106 to banjo players, 30 to the playing of the quills (or panpipes), and only 8 to drums. There are also numerous references to slaves playing musical instruments in the form of written advertisements seeking the return of escaped slaves, or in flyers where masters were attempting to sell slaves, which listed their musical talents as a sort of bonus to enhance the salability of the slave. Other instruments reported are the bones, the jawbone of an ass scraped with a wire or brush, tambourine, and the thumb piano (mbira).

The banjo itself seems to be a descendant of an instrument from Senegal called the halam, which like the five-string banjo has one string that runs about three quarters of the way up the neck of the instrument. In both instruments, the highest and lowest strings are adjacent to one another, and the African playing technique of using the fingernails of the right index and middle fingers and the thumb parallel early American banjo styles.

Some slave owners encouraged the slaves to play music, sing, or dance, feeling that it was a harmless diversion that could amuse the master and mistress. A happy slave was less apt to consider rebellion, might tend to work harder, and might have a better feeling about his or her life. On the other hand, the master could not really control the content of the slave’s songs. If the songs were sung in any sort of African dialect, dangerous information could be spread. Even without the use of the African language, lyrics could carry coded messages with different meanings for the slave and the plantation owner. A well-known blues song underscores this duality, stating, “when I’m laughing, I’m laughing just to keep from crying.”

Dancing might represent an even clearer danger to the master class, because dance is intrinsically sensuous and potentially erotic. The planter class was ambivalent about black eroticism, seeing it as a sort of devilish temptation not only to the slaves but also to their owners. Such eroticism might lead to potentially “immoral” behavior.

As slavery developed, it became increasingly centered in the southern states. For the most part, the north did not have large farms or need a labor force to work these farms. There was also a certain amount of early antislavery sentiment in the north from groups such as the Quakers in Philadelphia, who regarded slavery as evil.

African Musical Traits in African American Music

Various authors have delineated African musical traits that they feel are traceable in the music of black Americans. These traits include:

- Flatting of the third and seventh notes of the scale, and sometimes the fifth as well. (In the key of C these notes would be E, B, and G, respectively.)

- A metronome sense. Metronome sense is a clear delineation of where the beats of a measure are located.

- Music is functional, rather than designed to be “beautiful.” Worksongs were used while people were working; other forms of music might be used for dancing, for religious purposes, or for personal expression.

- Call-and-response singing. Call-and-response singing occurs when one person sings a part, and multiple voices answer. In his book Origins of the Popular Style, Peter Van Der Merwe points out that dialogue can be another form of call and response, as when a guitar answers a vocal phrase in a blues song.

- Special vocal techniques. These include melisma (the use of several notes in singing a single syllable) and specialized vocal techniques, such as falsetto or growling.

- Musical instruments. A number of African musical instruments were played by African Americans. These include the banjo, bones, mouth-bow, quills, tambourine, and diddley bow, a one-string instrument mounted on a board. Many of the early blues guitarists used the diddley bow as their first instrument, often in their childhood.

- Use of handclapping. There were numerous reports of the slaves “patting juba,” using handclaps as part of a dance or song.

Whatever parallels we find in African music and the blues, we need to keep in mind that we do not have any recorded examples of African music or blues from the late nineteenth century, the time when scholars believe the blues first evolved. We should also note that the savannah—the part of Africa that spawned musical instruments that were similar to the ones slaves played in America—was an Arabic culture, whose use of vocal shakes and vibrato is found in African American music. Arabic music also featured the lengthening of individual notes, a quality that puzzled some early white (and classically trained black) musicians when they first heard blues singers, because they could not understand the structure of the music. In other words, Africa does not contain a single musical style, or culture, and African influences are more complex than many scholars have acknowledged.

One of the confusing aspects of attempting to trace African elements in African American music is that the importation of slaves was continuous from 1619 until 1807. The slaves came from various tribes and linguistic groups, and there were differences in the music among the various tribal groups. Not only do we have to factor in all of the different tribes and languages that originally came here, but as new groups of slaves appeared, they in turn would be bringing in whatever influences they had been subject to at the time of their capture. These new arrivals interacted with second-and third-generation slaves, who to some extent were already integrated into American musical practices, or had developed their own fusions of African and American music. Since this is a 250-year period, and we know virtually nothing about African music at any point in the process, it is virtually impossible to make any definitive connections between “original” African music and the new African American forms that developed. Given these circumstances, scholarship necessarily turns into speculation.

African American Spirituals

The first music performed by African Americans that gained recognition on the larger American musical scene was the so-called African American spiritual. Many slave owners encouraged blacks to attend church, and the imagery of freedom from bondage on earth, “escaping” to a promised land, must have resonated with the slaves’ own situation of oppression. Plus, singing hymns would have been acceptable to the white masters, whereas secular songs and dances might have been seen as more threatening.

The first black minister given a license to preach was George Leile Kiokee, who set up an African Baptist Church in Savannah in 1780. In 1801, a free black man named Richard Allen published the first hymnbook for blacks, and established his own church. Allen used quite a few of the Isaac Watts hymns, and he also added lines and phrases to existing white hymns.

The first example of the music of black Americans in print appeared in 1867 in the book Slave Songs of the United States. Almost all the songs are hymns or religious songs, with a small representation of secular songs; so it reinforced the notion that African American music centered on the spiritual. The authors refer to improvisation of texts, and “shouting,” or dramatic emotive singing taking place in a circle or ring. This book’s 102 songs were collected from 1861 to 1864 primarily by the book’s authors—William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison—who were working in an educational program on the Port Royal Islands, off the coast of South Carolina. Allen, Ware, and Garrison found no musical instruments among the singers they knew, and remark that it was difficult to get freedmen to sing the older songs, attributing this fact to the ex-slaves repudiating the “undignified” aspects of their past lives.

Black religious songs were referred to as “Negro spirituals.” Spirituals were songs with religious themes, often looking toward a better life in heaven after the singer’s time on earth was over. However, the songs also sometimes contained double meanings, known as coded messages. The songs could have one meaning to the singers and a black audience, and an entirely different one to any white listeners. The messages could involve analogies between biblical oppression and the plight of the slaves, or could even offer directions for help in escaping from the plantation, as in the song Follow the Drinking Gourd.

Spirituals are generally regarded as folk songs that evolved through the process of oral transmission—songs that were passed on from one person to another and then changed either deliberately or accidentally. The spirituals were sung by groups of people, rather than individuals, and generally utilized the call-and-response pattern in which a singer would sing a line or a verse, and then the group would chime in with a response to that line, or would wait until the chorus of the song.

The first successful “serious” African American performing group was the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who performed highly arranged versions of spirituals in harmonized settings. Formed in the 1870s at Fisk University in Nashville to raise money for the all-black college, the group toured in the United States and eventually Europe, and made some early recordings of their “concert” versions of spirituals. They influenced countless other groups, and again helped solidify the notion that the spiritual was the “highest” form of African American music. Twenty-five of their songs were published in souvenir programs that were sold when the group performed, and in 1872, an entire volume of their repertoire appeared. This book went through many editions, and was very influential in spreading spirituals to a broader audience.

The Fisk singers were so successful in their fund-raising efforts that a number of other schools, such as the Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Choir, attempted similar touring and fund-raising efforts. Other groups not connected with schools also began to compete with the Fisk groups, including some bogus groups that attempted to use the “Jubilee Singers” name without permission. The performances by these groups leaned toward formal arrangements, often with piano accompaniment.

The history of the spiritual, then, involves European sources—early hymnbooks—that were reworked by African American musicians to form a new musical style. This interplay between black and white is typical of much of the history of American popular music. Nonetheless, throughout the twentieth century, there was an extended controversy as to whether white hymns came from black spirituals, or vice versa. The proponents for the white origins of spirituals were in effect arguing that African Americans lacked the superior inventiveness of their white compatriots. Black scholars took the opposite view, presenting a view of slaves as relentlessly creative human beings, endowed with more musical talent than their white contemporaries.

George Pullen Jackson, the foremost advocate for the white origin of spirituals, related the tunes of several hundred African American spirituals to tunes found in the British Isles. He also found parallels in the use of the flatted third and seventh notes of the scale that are usually attributed to African Americans. However, Jackson did not spend much time analyzing the texts, nor did he factor in the improvisational aspects of musical performances. Melodies in folk tradition are not stagnant, but change from one performance to another. Not surprisingly some black scholars claimed earlier origins of the black songs. These scholars pointed out that the first publication of the songs did not necessarily prove an earlier origin than songs that might have been sung without ever having been published. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. Dena Epstein sees the development of spirituals as an exchange of songs during the early-nineteenth-century camp meetings that both whites and blacks attended.

A number of black composer-arrangers, such as John W. Work, J. Rosamond Johnson, his brother James Weldon Johnson, and Nathaniel Dett, expanded on the work of the Jubilee Singers, and made formal musical arrangements of traditional spirituals. During the twentieth century virtually all black concert or opera singers performed spirituals. Some of the famous performers were Roland Hayes, Paul Robeson, and Marian Anderson.

When the Czech composer Antonin Dvorák visited the United States in 1893, he enthusiastically endorsed the work of the Jubilee Singers, and wrote a symphony, known as The New World Symphony, that incorporated melodies that were obviously derived from the spirituals. This work became influential and popular, spreading the influence of the spirituals in yet another arena.

Blues and spirituals share some common musical features, particularly the use of the blues scale. However, there are some fundamental differences between them. One is that spirituals usually referred to a better land awaiting the singers after death, while blues focused on the singer’s more immediate or practical needs, especially romantic ones. The blues also gloried in using bawdy images and double entendres, which were not acceptable in spirituals. To put it in another way, the blues were about the here and now, the spirituals were about the afterlife. Blues are generally performed by vocal soloists, whereas the spirituals almost always involved groups of singers.

The two musical forms came together by the 1920s in the form of holy blues—songs that utilized blues instruments and musical style, but had religious texts.

Early Black Secular Music

Various travelers, historians, and journalists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries make reference to the singing or playing of slaves. In addition to spirituals, they note several different forms of secular songs, including work songs, hollers, and ring shouts. Unfortunately, it was not until the late 1890s that folklorists started to collect folk music in the United States, and it was not until the 1920s that we had recordings of this music. This was also the period when blues, ragtime, and jazz were all developing. Consequently, it is difficult for us to know what the hollers sounded like in their “pure” state, when they were relatively uninfluenced by other musical styles.

One primary difference between the work songs, hollers, and ring shouts and later musical styles was that these songs were sung without any accompanying instruments. It is a safe assumption that more African traits can be found in unaccompanied music. We do have a number of recorded examples of work songs, and some of hollers, but they date from a much later time, and the work songs were mostly recorded in prisons. Writing in 1925, Dorothy Scarborough pointed out that work songs were sometimes performed by a group of people working together, but also might be sung by individuals in cases where slaves were working as a group, but separated from one another.

The Minstrel Show

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, black secular music came to the attention of many Americans through the vehicle of the minstrel show. Scholars date the earliest example of white performers using blackface to the late 1820s. By that time a half-dozen performers toured the nation, performing songs and dances between the acts of plays. Two of the most famous of these performers were Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice and George Washington Dixon. Author Robert C. Toll, in his book Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America, reports two of the tunes performed as Zip Coon (later known as Turkey in the Straw) and Jump Jim Crow. The two stereotypical characters of the minstrel show are represented in these two songs: Zip Coon was the well dressed city dweller who knew all the latest trends; Jim Crow was his rural brother, the country bumpkin who stayed home on the farm. In addition to dressing up as plantation black men by using burnt cork on their faces, white performers also sang in African American dialects. Some of the songs of the minstrels, such as “The Boatman’s Dance, passed into folk tradition, and were still being performed 100 years later.

Complete minstrel shows began during the 1830s, and featured skits, dances, and singing. They were, in effect, mini-theatrical performances that presented blackface comedy and song. There were actors, singers, and instrumentalists, especially banjo and fiddle players. Often the shows made fun of African American’s use of language, by presenting it as either pompous or foolish. The show’s master of ceremonies was known as The Interlocutor, and typically Tambo and Bones, two comic characters named for the musical instruments that they played—the tambourine and bones—made fun of him. Although slaves were generally portrayed as lazy, shiftless, fun-loving, and irresponsible, occasional minstrel productions depicted them in more human terms.

The first popular minstrel troupe was the Virginia Minstrels, formed in New York City in 1843 by four individuals who had achieved some fame as solo blackface performers: Billy Whitlock, Dan Emmett, Frank Brower, and Dick Pelham. E.P. Christy and his Christy Minstrels were among the most successful of the rapidly developing competitors of the Virginians. The music of these performers had a strong Irish-English tinge, blended with African American styles that many of the artists had heard from performers in the south, and sought to imitate. The banjoists often consciously imitated the work of black musicians, who themselves had been influenced by white dance music, as well as their own musical traditions. The later performing groups were larger, and often featured multiple musicians, two fiddlers and two banjoists, for example, instead of one. One of the most important composers who worked in the minstrel idiom, although not exclusively so, was Stephen Collins Foster, who wrote a number of songs that are still heard today, including Oh! Susannah and Old Folks At Home (popularly known as Swanee River). Foster was not a performer, but is often regarded as America’s first professional songwriter; one of his first and best customers was E.P. Christy, who took author credit for some of Foster’s first hits. Most of Foster’s songs were highly sentimental, and depicted the slave as yearning for his master and the old plantation.

Minstrel songs varied in their attitudes toward slavery. In addition to depicting “the old plantation,” some of the songs protested, or at least mentioned, that slavery often led to the breakup of families, as the master sold off a husband without a wife, or vice versa. Several scholars have pointed out that the very fact that there was so much interest in African Americans music and lifestyles was a step forward in the ultimate acceptance of African Americans into American life.

Minstrel shows were popular both in the cities and in the rural areas. Some of the companies had runs as long as 10 years in such cities as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. However, in the early days of the minstrel show, black performers were rare. William Henry Lane, known as “Master Juba,” was one of the few black performers in the early minstrel days. He was considered a magnificent dancer, and was victorious over John Diamond, his white rival, in dancing contests. By the end of the Civil War, many of the touring companies were black, although they were usually owned by white entrepreneurs. A number of jazz performers got their start playing in touring minstrel shows, including W.C. Handy, Ma Rainey, and Bessie Smith. Black minstrel groups drew black audiences, as well as the usual white curiosity-seekers.

By the turn of the twentieth century, minstrel shows were no longer popular in the northern cities, and were replaced by vaudeville shows. Performers such as Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor continued to perform in blackface, however, through the 1920s. The burnt cork tradition continued in rural communities up until World War II.

Early folklorists assumed that the negative imaging of the minstrel shows contributed to the abandonment of the banjo by black musicians. This seemed to be borne out by the fact that, prior to the mid-1970s, the Library of Congress collection of thousands of recorded songs and instrumental pieces included less than a dozen recordings of black old-time banjo players. However, extensive field research by Bruce Bastin, Cecilia Conway, and Tommy Thompson in the mid-1970s turned up far more black musicians who played the five-string banjo. Their picking styles were somewhat similar to those of white players in the Southern Appalachian mountains. This has raised some intriguing but unanswered questions about the relationship between white and black music, and who originated what styles.

The Early Blues

Social Conditions at the Birth of the Blues: 1870s–1900

After the Civil War, social conditions in the south appeared to change radically for the freedmen. The period 1865–1880 represented a period of hope for southern blacks. There was a general optimism among African Americans, who felt that they were “free at last, free at last.” Slavery was abolished, some ex-slaves were able to buy land, and they voted in local and national elections. African Americans were elected to state offices and to the U.S. House of Representatives, and there were even a few elected to the U.S. Senate. Northern troops occupied the south, and missionaries established schools.

However, northern troops withdrew from the south in 1877, and conditions quickly deteriorated. Freedoms were curtailed, and many blacks were barred from voting—either outright or through the imposition of restrictive “poll taxes” or fees charged to exercise the right to vote. The sharecropping system, in which whites owned the land and black workers were forced to pay rent for its use, became common. The blacks also often had to purchase seed and other supplies from the landowners, often at inflated prices, so that most—if not all—of their harvest went to repaying loans and rent. The system was in effect similar to slavery, and some of the sharecroppers were perpetually in debt to the landowners. To aggravate matters, the northerners largely lost interest in the freedmen, and various political deals were made that removed any federal control over the racist practices prevalent in the south.

It is possible to make the case that it was the very nature and extent of repression that led to the dynamic emergence of new musical forms. In Bleaching Our Roots: Race and Culture in American Popular Music, performer-scholar Dave Lippman makes the interesting point that the slave owners, attempts to repress African music necessarily led to the development of new and unique musical forms by the slaves. We can hypothesize that the repressive period of 1890–1920 similarly led southern African Americans to create new musical forms.

The Blues: 1890–1920

Unfortunately, we do not have much in the way of printed texts to show us how and when the blues evolved. No one was very interested in secular black music in the late nineteenth century, and of course there were no tape recorders available. What blues scholars have written about really stems largely from the recordings and recollections of the older generation of black blues artists, none of whom recorded before 1920.

However, there is one key source for studying the early blues. Howard Odum collected music in Georgia and Mississippi in 1905–1908 and published his work, initially in The Journal of American Folklore, and some 20 years later in two books of songs, coauthored by Guy Johnson. Odum published the first blues, and much of what we have said about the form of early blues comes from his researches. Unfortunately, his books do not specify which songs were collected in which states. Alan Lomax calls Mississippi “the land where the blues began,” but we have no absolute evidence that this is literally true. We do know that the ways in which the blues developed vary in different regions […].

Odum classifies early blues musicians into three categories:

- The songster was a musician who performed blues, but also had a repertoire of many other songs, such as spirituals, work songs, and ballads.

- The musicianer was an instrumentalist.

- The music physicianer was a musician who traveled, and wrote and played his own songs.

It is possible that the songsters were the bridge between earlier black music forms and the blues. When one remembers that such musicians played for both black and white audiences, and would be attempting to please both groups, this seems even more plausible. The traveling music physicianers would then serve to spread the music far and wide, at least to the black populations in various parts of the country. The distinction between these various musicians has been overdrawn, in the sense that many musicians performed blues, other secular songs, and even religious tunes, and some musicians, such as Lonnie Johnson, sometimes recorded as vocalists, sometimes as an instrumental soloists, and sometimes as accompanists for other vocalists.

Another key early source for our knowledge of the blues comes from musician-composer W.C. Handy. In his autobiography (published many years later), Handy recalls seeing a black musician sitting by a railroad station in 1903, playing guitar with a knife in his left hand and singing I’m goin’ where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog. Handy found that this song referred to a railroad junction in Morehead, Mississippi. There are other reports of the blues sung during the 1890s in the memoirs of various black musicians. Some blues singers have claimed that the song Joe Turner was the first blues song, and the others that developed were variations on it. Turner was a penal officer who transported convicts in Tennessee between 1892 and 1896, certainly the correct time period for the beginnings of the blues.

Handy was a trained musician who realized that the blues could bring him income and popularity. Not long after his first experience of hearing the blues, Handy’s band was playing a dance in Cleveland, Mississippi, and saw a guitar, mandolin, and string bass trio play during the intermission of their show. The audience rewarded the trio’s efforts with “a rain of silver dollars,” causing Handy to immediately realize the financial potential of the folk blues. Because Handy was a bandleader, he needed to formalize the structure of the blues, and to write the blues down in sheet music form. Handy’s Memphis Blues was published in in 1912, and his St. Louis Blues appeared in 1914. Handy used the AAB lyric form, and his songs were usually 12-bar blues (we will discuss the structure of a blues song shortly). The first blues vocal to be recorded was Handy’s Memphis Blues, but, ironically, it was recorded by white musician Morton Harvey.

Handy’s success inspired countless others to write “blues” songs, and this repertoire became known in the 1910s and 1920s as the “classic blues.” Unlike their folk forebears, classic blues were composed blues songs, generally with a definite musical structure and a story line, and they were sung by female singers, many of whom were experienced performers, used to singing in front of theater audiences. This was very different from the style of folk blues, which were performed before small, informal audiences, or at dances. […]

Subject Matter

The blues that Howard Odum found in Georgia and Mississippi before 1910, like the blues that are sung today, were largely about romantic situations between men and women. Some of the songs contained boastful lyrics about the sexual prowess of the singer, some were self-pitying lyrics about unfaithful women, or double-dealing friends. Some are simply celebrations of sexuality, others of the virtues or difficulties associated with drinking. Another common subject was travel, and often the railroad was mentioned either as a way to escape the often oppressive small-town life, or simply to enjoy a change of scenery. Many blues refer to specific towns or states of the singer’s acquaintance. In an unfriendly world, jail was inevitably a possibility, and jail, judges, and prison guards make their way into early blues lyrics. Odum acknowledged that he was unable to print some blues lyrics on the basis of their immorality, the use of “unacceptable” sexual references. The same held true of some later collectors. Consequently, we will never know how many bawdy songs simply never appeared in print.

Various scholars have argued that the blues are a form of protest music, with the singer complaining about his lot in life. Others deny that protest is a significant aspect of blues style. Even in Odum’s work we find complaints about jailers, bosses, and work. It is also important to remember that all of the early collectors were white. Many of the singers may have not trusted these scholars enough to sing songs that complained about their lives, or protested specific occurrences. We will return to this subject when we discuss Lawrence Gellert’s collections of protest songs from the 1920s and 1930s.

Sometimes early blues lyrics did not tell a single coherent story, but rather used a number of unconnected images of what was floating through the singer’s mind at the time of the performance. Sometimes this included combining verses from other songs, and transforming them into “new” creations. There were certainly a number of well-known blues verses that surfaced in various songs. After blues started to appear on records during the 1920s, the pirating of verses from various songs became a common procedure. Sometimes entire songs were “borrowed,” with only the most minor changes, such as the singer changing the caliber of a gun or the name of the female protagonist in a song. This is partially due to the fact that record executives demanded that singers “write” their own material, hoping to benefit from ownership of their copyrights; many singers were not talented writers, and so took to reworking older songs in an attempt to pass them off as their own.

Although the slow blues definitely had a plaintive quality, faster tempo blues made good dance or party music. At times a sad lyric was combined with an up-tempo melody, or a faster tempo could mask the feelings of sadness in a thoughtful lyric. The blues had room for a wide range of emotions.

Ragtime and Early Jazz

The beginnings of ragtime and jazz virtually paralleled the development of the blues form. In ragtime, unlike the blues, the piano was the main instrument. The early ragtime pianists were barroom players, who did not necessarily read music. Ingredients of ragtime began to appear in the pop songs of the 1890s. Known as “coon songs,” these songs enjoyed enormous success and, as one might expect, treated African Americans in a derogatory fashion. They were essentially a repetition of the images that minstrels had painted of African Americans. Ironically, some of the composers of these songs were themselves black.

Instrumental ragtime developed during the 1890s, primarily in St. Louis and Sedalia, Missouri, but also in New Orleans. Eileen Southern, in her pioneering book The Music of Black Americans, also mentions piano players in such cities as Mobile, Alabama, Louisville, Kentucky, Memphis, Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York. As instrumental ragtime developed, it became very complex, containing as many as four different musical parts to a song. Composer-performers such as Scott Joplin or James Scott were sophisticated, trained musicians, who thought of themselves as serious composers. The first recorded ragtime pieces appeared in 1912 in two piano rolls recorded by the legendary black piano virtuoso Blind Boone; Joplin made some rolls well after his playing career was over 3 years later.

Ragtime piano was a sophisticated musical style, with the right hand playing syncopated or offbeat figures while the left hand kept the rhythm steady. Not only were such pieces as Joplin’s work divided into different sections, there were often key changes from one section to the next. Gilbert Chase, in his book America’s Music, suggests that the right-hand piano syncopations were derived from black banjo styles played on the five-string banjo. In these styles of banjo playing, the thumb played the fifth string of the banjo, sometimes playing that string off the beat.

Although ragtime was sometimes played on the banjo, the primary impact of ragtime on the blues was in the Piedmont guitar styles of the Carolinas and Georgia. As we will see in the next two chapters, these styles required a more sophisticated harmonic approach to the guitar than that of the folk blues players. The most advanced players, such as Blind Blake, wrote guitar instrumentals, rather than just using the guitar to accompany songs.

Most scholars agree that New Orleans was the central place where jazz developed, although there were black brass bands in various parts of the country in the middle of the nineteenth century. New Orleans had a particularly rich tradition of brass bands, dating from the 1870s. Sometime toward the end of the century, these musicians started to modify ragtime, and “swing the beat.” The legendary cornetist Buddy Bolden was probably among the first of these early jazzmen. By the turn of the century such African American musicians as trumpet players Freddie Keppard and Bunk Johnson started to play downtown with the Creole musicians, and New Orleans jazz was born. However, by 1915, many African Americans moved out of the south, and in 1917, the U.S. Navy closed down the Storyville district. Storyville had been the entertainment center of New Orleans, complete with bordellos that employed many musicians. The next developments in jazz took place in Chicago.

Jazz utilized some of the harmonic devices of ragtime, but kept the spirit of the blues. The brass instruments moaned, growled, and bent notes to simulate blues growls and trills. The typical New Orleans combos had trumpet, trombone, and clarinet, and the rhythm section had a tuba instead of a string bass, a banjo, and a small drum set. In a good number of early jazz arrangements, the music was not written down, but was improvised, with beginnings and endings of songs worked out. The solos were entirely improvised.

Many of the early jazzmen played on records by the classic blues singers in the 1920s, although usually with small combos using only a handful of musicians. Oddly the first jazz recordings were made by a white group, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, in 1917.

Blues Structure

When we discussed W.C. Handy and his composition, we mentioned the lyric structure (AAB) and the form “12-bar blues.” Students of the blues are familiar with these terms, but for others they may be slightly mystifying. Here is a brief explanation.

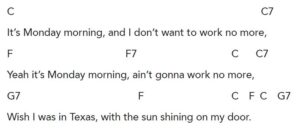

If we look at the way blues are performed by a contemporary artist, such as B.B. King, it is easy enough to analyze the musical and lyrical structure of one of his songs. Almost invariably the songs will be in 4/4 time, which means that there are four quarter notes in each measure of music. The verses will contain twelve bars of music, and the chord structure will usually consist of three basic chords, built on the first, fourth, and fifth notes of the scale. In the key of C, these chords will be C, F, and G7, with the C going to a C7 and the F chord moving to an F7. The lyrics will be in AAB form, which means that the first line of the song will be repeated, with the third line acting as a sort of answer to the previous (repeated) lines. The end of lines one and two typically rhymes with the end of line 3. An example, with the chords written in, is:

Notice that there is a short chord sequence at the end of the verse. This is called a turnaround, and it leads back to the next verse, which will start with the C chord.

This is all very well, except that when we start to look at the origins of the blues, and how they developed, we find a number of disconcerting things. First, the earlier folk blues did not always contain twelve bars. They might have eleven, or thirteen, sixteen, or even twelve-and-a-half bars. It is quite possible that the twelve-bar form developed when musicians started to play together, or when a singer was accompanied by a guitarist or pianist. As soon as two or more musicians play together, they need to have some agreement about the length of musical phrases in order to stay together. Or perhaps Handy, being a “professional” musician, simply “evened out” a form that in the folk tradition was much more flexible. Blues did not always use three chords, either. Some of the Mississippi blues really consisted of a single chord, slightly modified to go with the melody of a particular song.

The lyrics were equally irregular. Howard Odum, working in 1906–1908, found that there were songs that consisted of a single repeated line, with no additional lyrics. Other lyrics patterns consist of a verse that has an opening line, with the second line repeated, instead of the first line as shown in the example above. This form can be indicated as an ABB form. An example is:

Ain’t no more cotton, cause the boll weevil ate it all,

Gonna leave this town, goin’ away before the fall,

You know baby, I won’t be here next fall.

Notice that in both lyrics the repeated lines are not identical. They are almost conversational, as though the singer is thinking about the lyrics as he sings.

The forms that blues songs can take are seemingly endless, and sometimes vary within a single song. I have an out-of-print recording by Hally Wood where she sings a song called The Worried Blues. The first verse goes like this:

I’ve got the worried blues,

I’ve got the worried blues,

I’ve got the worried blues, oh my Lord;

I’ve got the worried blues,

I’m going where I’ve never been before.

I suppose we could call this form AAAAB. But, later in the song she sings

I’m going where those orange blossoms bloom,

I’m going where I never been before,

I’m going where those orange blossoms bloom, oh my Lord;

I’m going where those orange blossoms bloom,

I’m going where I’ve never been before.

We might call this form ABAAB. The point is that the blues singer created the form around the lyrics of the song, rather than tailoring the lyrics of the song to fit a preconceived model.

At the turn of the twentieth century, there were ballads that had many elements of blues songs, but did not follow these lyric structures. For example, in the song Frankie and Albert—a version of the song Frankie and Johnny sung by Mississippi John Hurt and Leadbelly, among others—there is a recurrent last line (“he was her man, he was doin’ her wrong”). In Furry Lewis’s version of the ballad Casey Jones—which he calls Kassie Jones—he repeats the last (fourth line) of each verse. This form of song, with a repeated last line, is known as a “refrain,” and is common in Anglo-American balladry as well.

Just as the blues make use of repetition in the construction of their lyrics, the same patterns also can be found in spirituals, and in traditional English ballads. For example, here is a verse of the sixteenth-century ballad Pretty Polly, a song that has been collected in numerous versions in the southern Appalachian mountains:

I courted pretty Polly, all the livelong night,

I courted pretty Polly, all the livelong night,

I left her next morning, before it was light.

The spiritual Lonesome Valley has been collected from both white and black singers. It uses a different pattern of repeated phrases:

You’ve got to walk that lonesome valley,

You’ve got to walk it by yourself,

Ain’t nobody here, going to walk it for you,

You’ve got to walk that lonesome valley by yourself.

In this instance, the lyric is not a word-for-word repetition. The second line is slightly different from the first line, and the fourth line combines elements from the first and second lines.

Learning to Play or Sing the Blues

Before we proceed with the history of the blues, it might be useful for the interested reader to get a glimpse of how to learn to play or sing the blues. The earliest blues singers developed their knowledge of the music as a sort of communal experience, in the same way that communities in such diverse places as Bulgaria and West Africa have nurtured and developed their musical traditions. The Carolinas nurtured and developed the Piedmont blues, while in Texas and Mississippi relevant but different musical styles emerged. Further refinements that scholars ponder over include the differences between the delta Mississippi blues style that developed in the Clarksdale area, and the somewhat different and less intense Mississippi school that emerged around Bentonia, north of the city of Jackson.

One hundred and ten years later these local communities where music could be learned directly from older master performers no longer really exist. So how does the reader, black, white, or otherwise, learn how to play or sing the blues? The most typical path that people follow is to immerse themselves in the musical style through listening to CDs, watching videos, and buying instructional books and tapes. Fortunately, these resources are readily available in most cities, and if you do not live in a relatively large urban area they are available through mail order or internet purchases. In the appendix of this book is a large list of resources that can help. But let us discuss the way that these resources can be utilized most efficiently.

From the author’s point of view, the most useful way to learn about a musical style, blues or otherwise, is to have as much direct contact as possible with a person or people for whom that style is natural. In other words, your best bet is to be around blues singers, players, and bands. The reason that this sort of immersion is the most successful way of learning about the blues is that not only will it show you the specific musical ways that, for example, a guitar is played, but it will also give you some feeling for the more subtle aspects of the music. In addition, you will begin to develop enough of an ear to understand what distinguishes one particular player from another. Mance Lipscomb and John Hurt had a similar feel in their playing, but they do not sound alike. Muddy Waters developed out of the Clarksdale tradition that spawned Robert Johnson, Son House, and Charley Patton, but Muddy really did not sound anything like these other blues artists. Each had certain distinguishing traits, whether right-hand picking styles, the use of musical dynamics or different guitar tunings, or vocal styles that could involve falsetto (a sort of fake high tenor) singing, grunts, doubling what the guitar was playing, and so on.

It is more convenient to learn from instructional videos, CDs, and books than to seek out artists who actually play and sing the blues. The problem with learning from these valuable resources is that they are tools, not substitutes for trial-and-error musical experiences. The same thing applies to taking guitar, piano, or vocal lessons. Blues is an improvisational genre of music, and although students often must go through a process of imitating a specific musician, this ultimately can be counterproductive to developing individual approaches to the music. So, the author recommends singing and playing along with records only up to a point. There should come a time when you put other people’s styles away, and you make the choice to try it your own way.

Whether or not you will turn out to be a musical innovator is impossible to predict, but there is a great deal of joy to be experienced in playing your own songs, your own instrumental solos, or even your own musical arrangements of old standards.

The blues began around 1890, possibly in Mississippi. The musical aspects of the blues utilized a number of African traits, and lyrics of the early blues were written in a stream-of-consciousness manner. Rather than telling a specific story, they reflected the moods and memories of the singer. The earliest blues were probably unaccompanied, but the instrument of choice quickly became the guitar. Blues drew on a variety of black popular styles, including spirituals, hollers, and worksongs, and European elements borrowed from ballads, dance tunes, and religious songs. Trained black musicians began to formalize the structure of the blues after 1910, and many of their more structured and pop-oriented songs were sung by women professional performers. Jazz and ragtime developed in a parallel stream to the blues, and these musical styles influenced one another.

Bibliography

The Blues and Africa

Oliver, Paul. (2001) Savannah syncopators; African retentions in blues. Reprint of 1970 book, with a new afterword in Yonder Come the Blues.

The Minstrel Period

Toll, Robert C. (1974) Blacking Up: the Minstrel Show in Nineteenth Century America. New York, Oxford University Press.

Social and Musical Background of the Blues

Allen, William Francis, Charles Pickard Ware, Lucy McKim Garrison. (1867) Slave Songs of the United States. New York, Peter Smith, 1951 reprint.

Conway, Cecilia. (1995) African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A Study of Folk Traditions. Knoxville, TN, University of Tennessee Press.

Epstein, Dena J. (1977) Sinful Tunes and Spirituals. Urbana, IL, University of Illinois Press.

Odum, Howard W. and Guy B. Johnson. (1926) The Negro and His Songs. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press.

Scarborough, Dorothy. (1925) On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Southern, Eileen. (1971) The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York, W.W. Norton.

Van Der Merwe Peter. (1989) Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music. New York, Oxford University Press.

Biographies and Autobiographies

Handy, William Christopher. (1941) Father of the Blues. New York, The Macmillan Company.